Sarah Glidden wants her non-fiction comics to be a ‘gateway drug’ to learning about tough issues

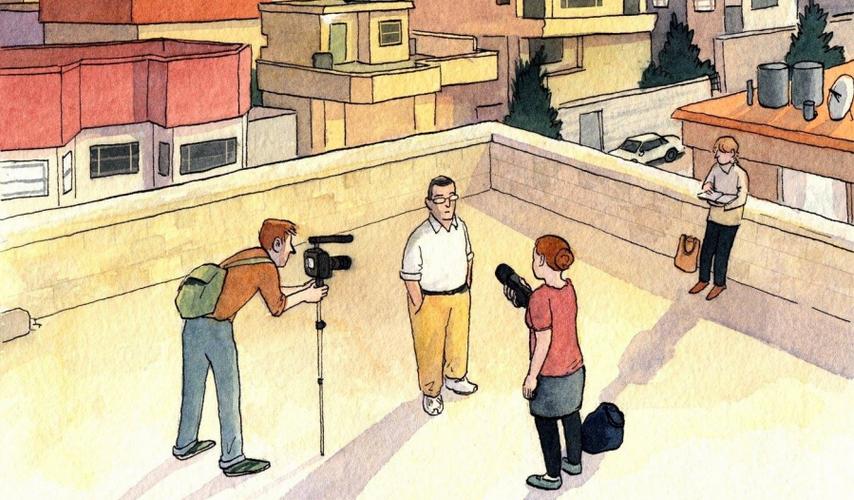

In 2010, cartoonist Sarah Glidden spent a month traveling around Turkey, Syria and Iraq. She'd tagged along with some old friends, journalists from The Seattle Globalist who were on a reporting trip to tell stories about refugees. Glidden went along to document what it's like to be inside the journalistic sausage factory.

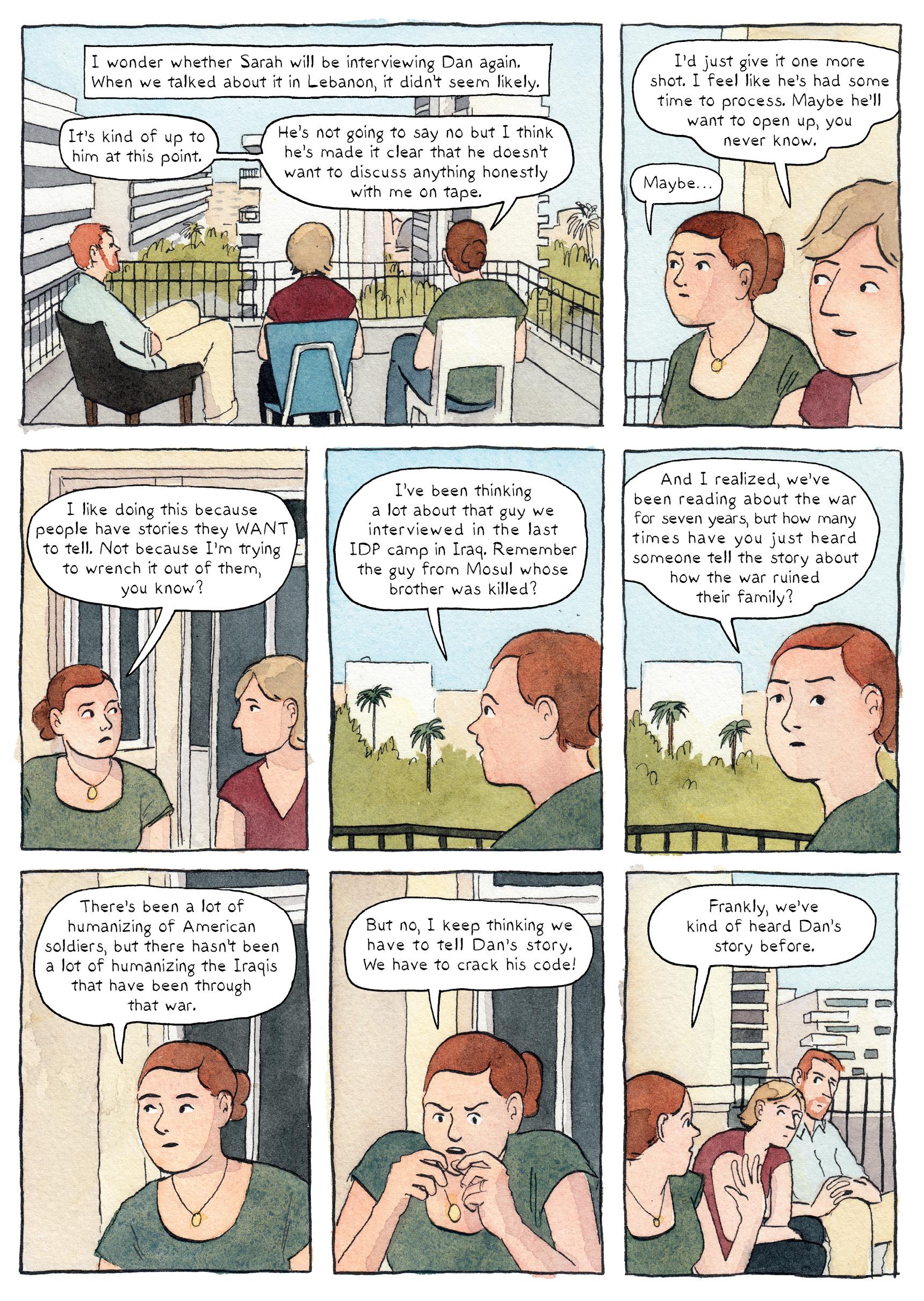

Glidden quickly saw the conflicting pressures the reporters were under.

"You know, journalists really care about the stories they're working on, but they also have to think about marketing, their audience, and how they're going to get someone to take time out of their day and read their article or watch their documentary. And this is a struggle I think that all journalists have to go through. I just really wanted to show that process."

Then there was the fact that the people she was traveling with and drawing about were friends. She'd built up a rapport with them over eight years. "I think it made it easier and more difficult. Easier because they already trusted me. So they could talk to me openly about how they felt about their work."

One of the most jarring things about reading "Rolling Blackouts: Dispatches from Turkey, Syria, and Iraq" is that it shows Syria in 2010, when the country was a safe and relatively prosperous place in the region. Glidden says she shudders when she thinks of Syria today.

"Syria, at that time, there were tourists everywhere. We met lots of people our age taking Arabic lessons. It was a very popular place to learn the language. We could never have guessed what was coming in just a couple months."

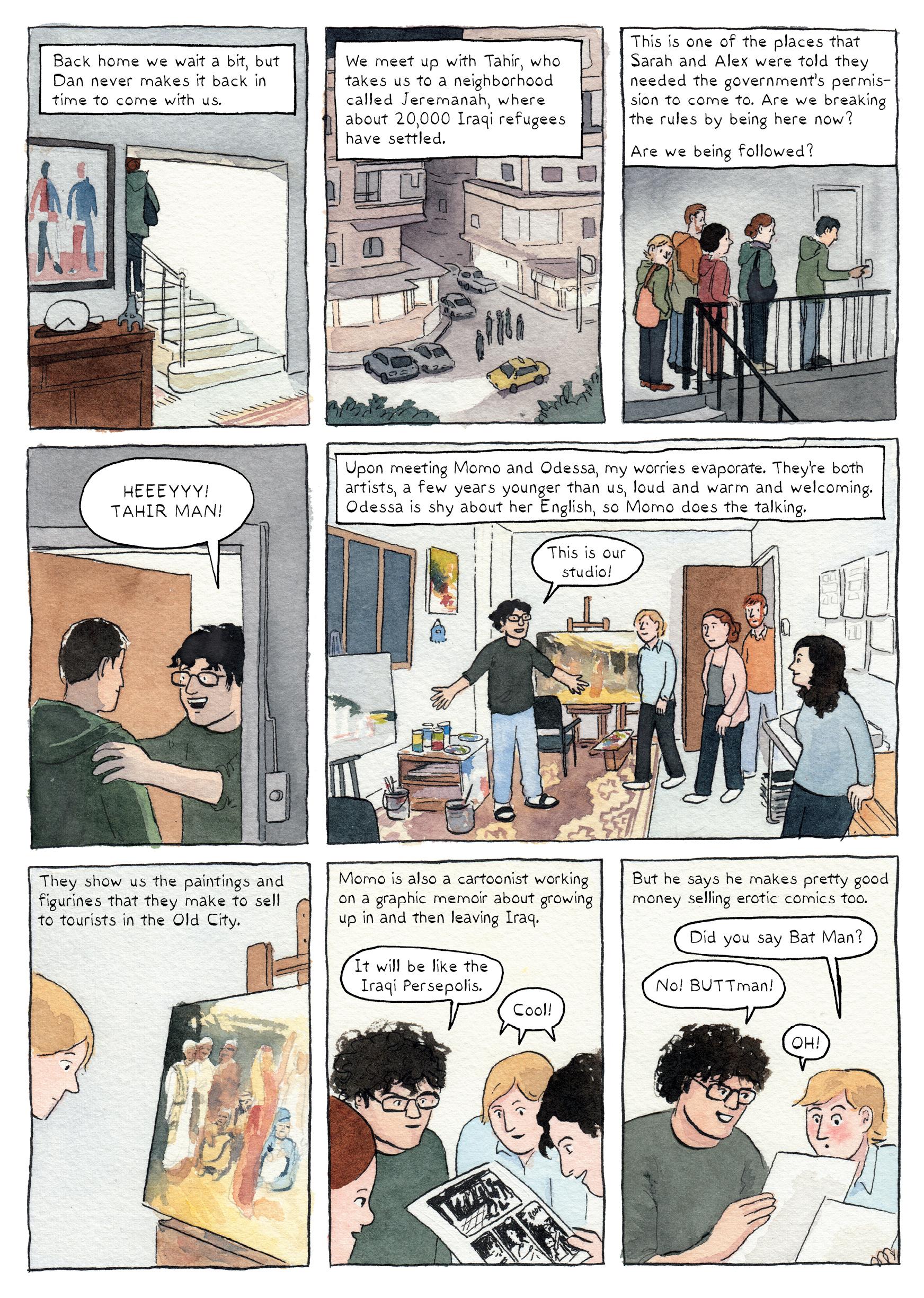

Syria was also a go-to place for Iraqis fleeing war. By 2010, there were about a million Iraqi refugees living in Syria. Two of them were Momo and Odessa. They seemed so familiar to Glidden. They could have been artist hipsters living in Seattle.

"Meeting them was just like meeting someone who was already your friend. They were both artists. They were both painters and Momo is also a cartoonist, working on a memoir about growing up in Baghdad and being a young man when the invasion happened and then his escape to Syria." She said they shared shop talk and compared notes on their favorite cartoonists. That shared identity made an impression on her.

"One thing I wanted to show in this book is that I could be a refugee if [I] were in a different place in a different time. This is someone who I think a lot of my readers can identify with, and yet here he is fearing for his safety, now living in Syria, which is a safe place, but a place where he was separated from his friends. He couldn't do the work that he used to do separated from his family, some of whom are still in danger. Just how impossible it is to imagine being in his position."

Then there was the Iranian blogger living in southeastern Turkey after fleeing there with his wife over the mountains. Glidden assumed he'd gotten in trouble for blogging. Not true.

"It turned out he had been publishing books, books that were not approved by the [Iranian] government. And he was put in jail because he was being questioned over those."

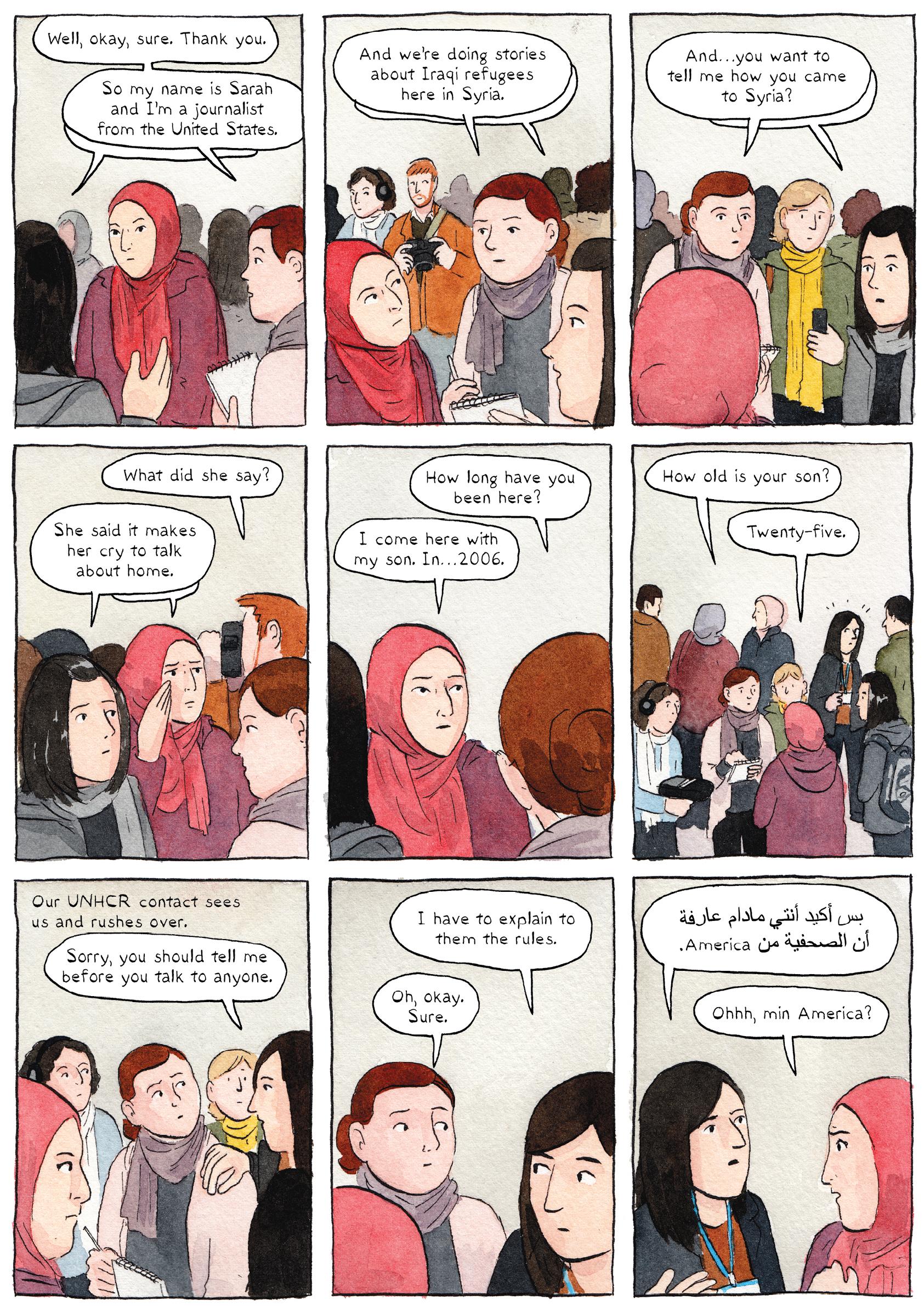

Glidden says the blogger and his wife were the first refugees she and her friends met and through them, they learned a lot about the process of becoming a refugee.

"I realized how many of my own assumptions I bring to people based on what I know about their country, the limited amount of information that I've gotten from the news. You hear about someone and you assume why they've been in jail. That was kind of a big lesson for me right away that you need to have the interview first. You need to actually talk to someone before you think you know what their story is."

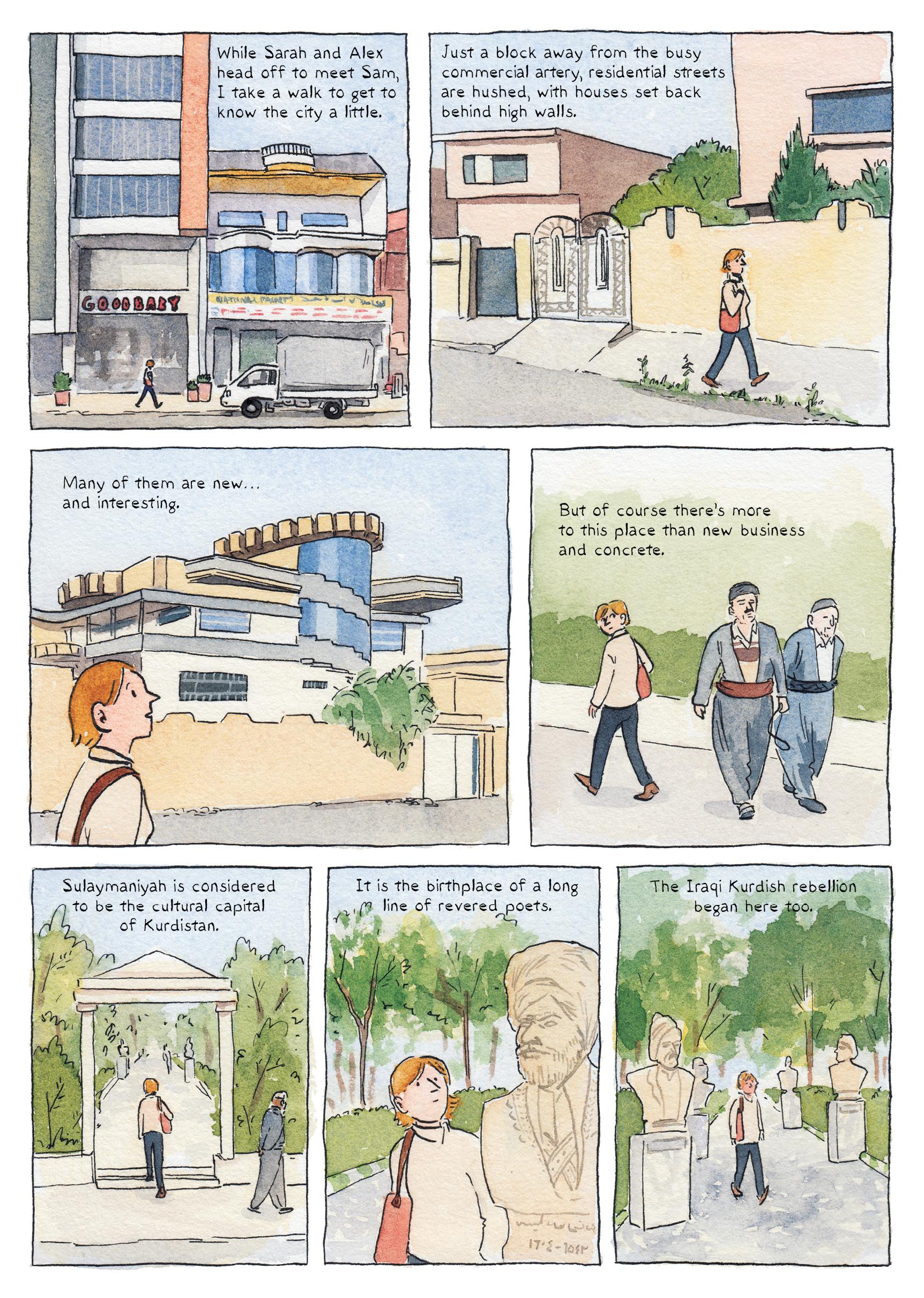

"The book was all drawn when I got back, because when all this is happening, you really don't have the time to sit and draw," she says. Glidden did use her sketchbook at locations where she wasn't allowed to take photos, like border crossings or in very personal interviews. "Mostly I take a lot of pictures so that I can be very specific about the place. I want people to be able to recognize Damascus or recognize Sulaymaniyah in northern Iraq when they read the book."

Glidden doesn't consider her non-fiction comics to be the last word on any subject. Just the opposite, in fact.

Every day people are bombarded by articles and photographs on their social media feeds. But Glidden believes "comics can bring a real human connection and be a gateway drug to an issue for people."

"I think sometimes people feel desensitized to these stories about war and hardship. I think that comics can make people look again because right now, non-fiction comics are still relatively new, and hand-drawn images and hand-painted images might make someone take a second look."

Glidden wants her work to grab people and lure them in. "And once they're there, I hope that the comics can give someone an intimate connection to an issue that might be more difficult when there's a mechanical layer between them and the story as with prose or photographs."

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!