Harvard has a $35 billion endowment. Its dining hall workers are on strike for a $35,000 minimum salary.

Striking dining hall workers at Harvard University say they have the support of much of the student body and faculty on campus.

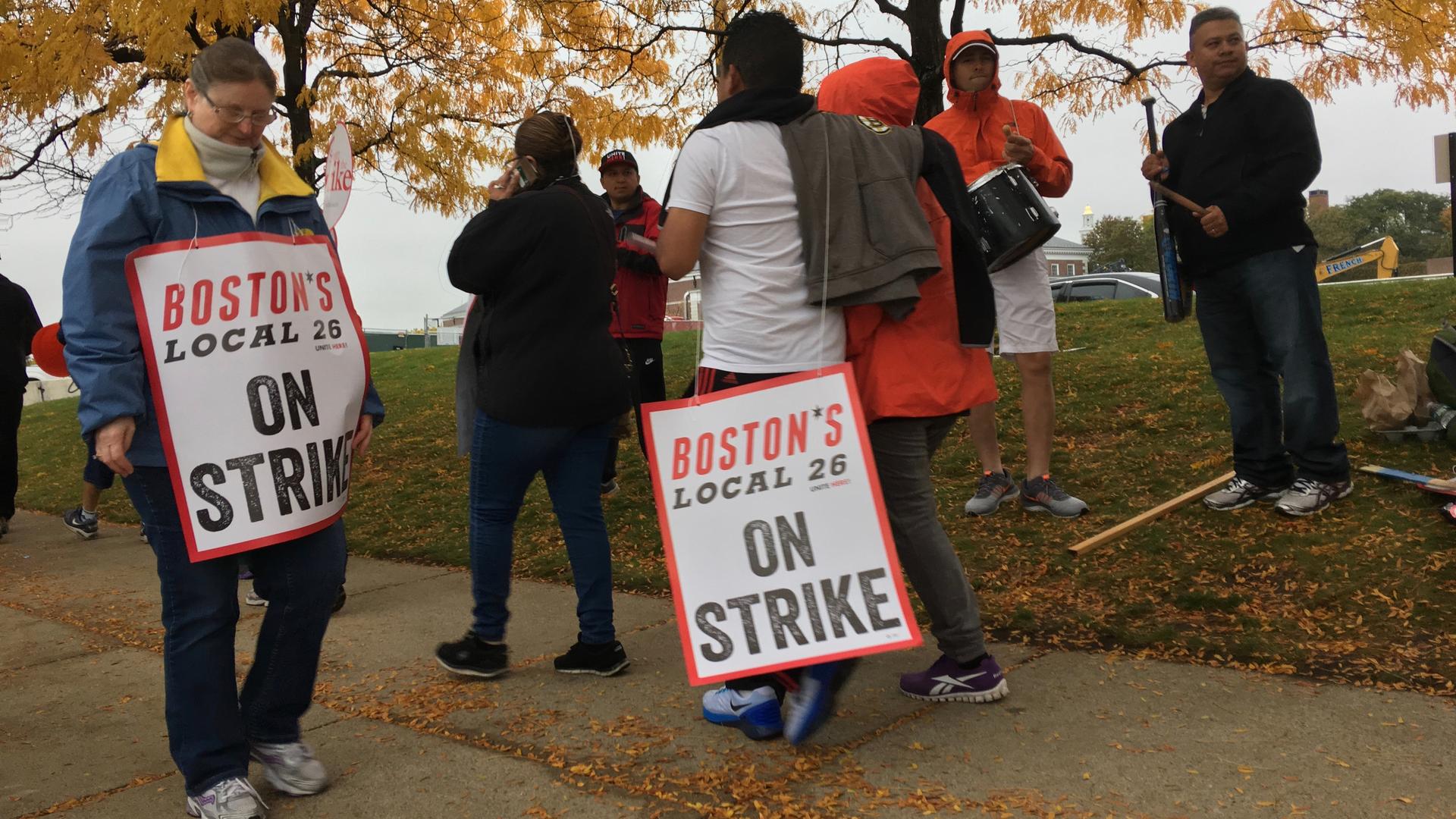

Bullhorn in hand, union organizer Kelly McGuire flips between Spanish and English as he rallies a group of striking dining hall workers outside of the Harvard Business School on this damp and gray weekday morning.

“We know what we’re doing is working. We gotta keep pushing,” says the red-bearded McGuire, a representative of Unite Here Local 26.

Negotiations between the union and Harvard University started back in May. Then, two weeks ago, more than 700 cafeteria and food service workers walked off the job.

The workers want better pay and benefits. They’re demanding a $35,000 minimum salary for full-time workers, and they oppose increases in employee contributions to health care costs, which average between $3,000 and $4,000, per family, every year.

Dining hall workers at Harvard currently make $21.89 an hour, on average, according to the university.

“Harvard has among the highest hourly wages, but because so many workers do not collect unemployment and have low hours, they fall behind in overall annual income,” says Tiffany Ten Eyck, also of Unite Here Local 26.

Ten Eyck calls that “shameful for a university of its resources.”

Harvard University has an estimated endowment of more than $35 billion.

The dining hall workers voted to authorize a strike in mid-September, 591 to 18. But Dora Gladys Romero was reluctant at first.

“You don’t know what we’re walking into,” she says.

Romero is a 55-year-old dining hall steward who has worked at the Harvard Business School for the last 12 years. She says she came to the US about 40 years ago, helped raise five kids here, and now, both she and her husband rely on the health care benefits she gets from Harvard.

Romero says she loves her job and wants to keep it, but Boston is an expensive place to live.

“I’m paying $2,600 a month,” she says. “You think 20 dollars an hour is enough?” And she wonders how her co-workers who still have children in day care or at college manage to make ends meet.

On Friday afternoon, Romero was among a small group of women arrested for blocking traffic in Harvard Square. Both she and Any Montoya, 32, say they had never done anything like that before.

“It was scary, of course,” Montoya says. “But I didn’t feel alone. I feel that I could do it, and I did.”

Montoya says she went to a few protests during her college years back in Colombia, where she grew up. But those demonstrations turned violent and she didn’t want to take the risk. She says she joined the group of women to block traffic on Friday to send a message to the university, to show that striking dining hall workers were not powerless.

“Obviously, it was no violence. We are not criminals,” she adds. “We’re just speaking up.”

The charges against Romero, Montoya and seven other workers were dropped. But they will still have arrest records.

Harvard says it is ready to talk with the workers’ union to find what it calls a “fair and reasonable resolution.”

Another veteran from dining services at Harvard Business School, Antoine Gabriel Bourghol says that the university is a great place to work. Bourghol, 70, was born in Aleppo, Syria. And he says he still believes in the Harvard brand.

“As a union worker, you are proud, that to be working with this institution, to build a better society and a better world,” says Bourghol. “But also I believe that Harvard is directed by human beings and they can do, a lot of time, bad judgment.”

Bourghol, who’s known as Gaby to his union colleagues, said it was the added health care costs that Harvard wanted to push on to employees that made him want to join the first strike at the university in more than 30 years.

For now, Bourghol says he will continue to show up every morning on the picket line. He says he’s also refusing to accept any strike pay from the union.