Olelein Kanunga is trying to persuade fellow Maasai warriors to take up the fight against female genital mutilation.

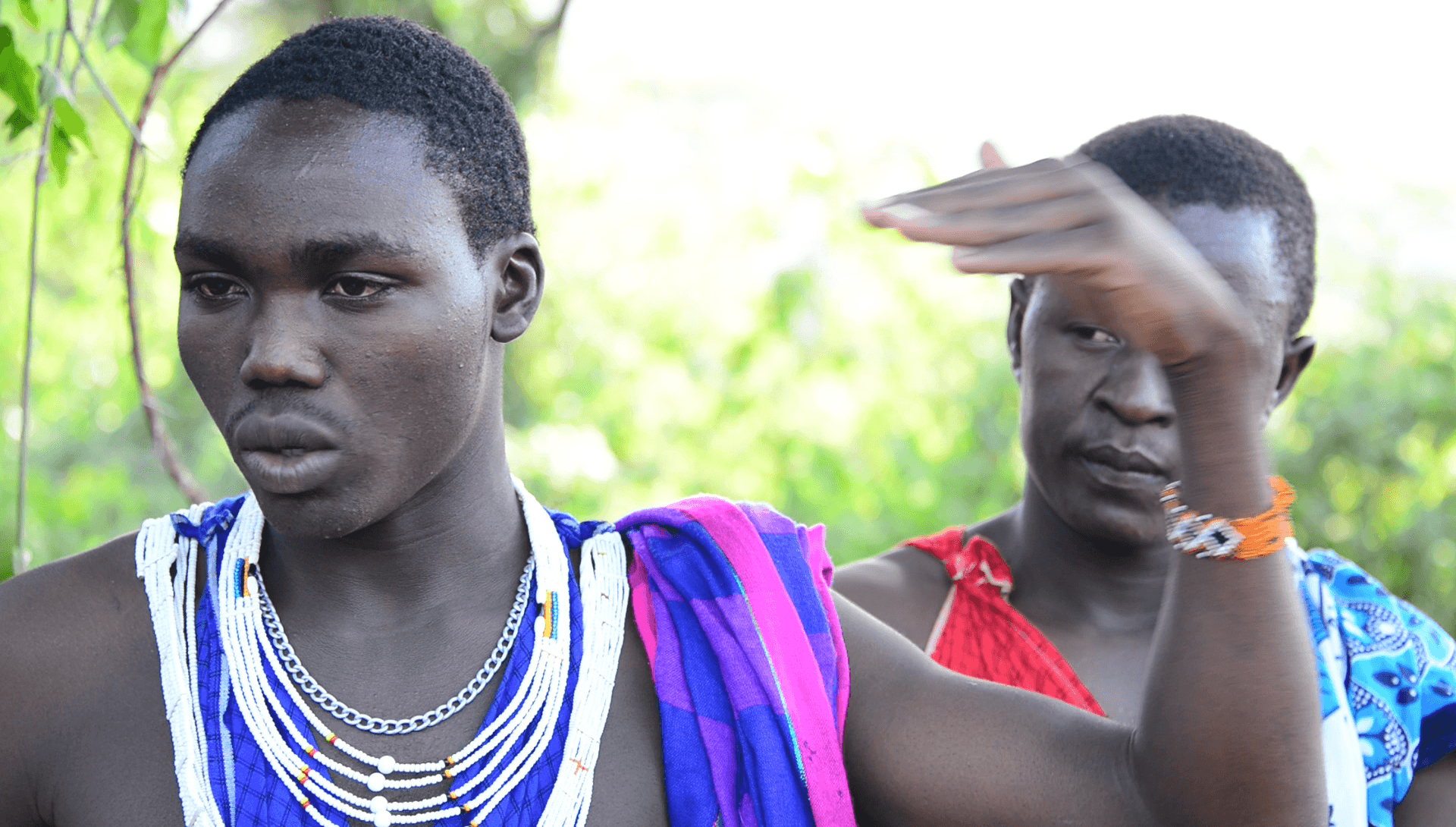

Dressed in colorful red, blue and white cloth, with necklaces of white beads adorning his chest, 28-year-old Ole Lelein Kanunga sings and dances with his fellow Maasai warriors. He is carrying a long dark-brown stick, symbolizing that he is their leader.

The dance, the attire, the symbolism — it's all very traditional. But Ole Lelein is also a revolutionary. He wants to end the practice of female genital mutilation, or FGM, among the Maasai in southern Kenya.

A few years ago, he attended a workshop about health issues that changed his life.

"While at the workshop we heard news that a girl who had gone through FGM was bleeding uncontrollably and was almost dying. This made me think — what if that was my daughter. This is when I decided I will not let my daughters go through FGM. I also decided that I would start a campaign to help my community to stop this act,” he says.

Ole Lelein has been striving to end FGM in his conservative Maasai community ever since.

As part of his campaign, he gives talks under trees where he invites young Maasai men to discuss the dangers of FGM.

Little by little, the movement has grown.

Ole Lelein receives funding and training for his work mainly from Amref, a nonprofit that operates all over Africa. The idea is to use his position as a Maasai warrior leader — in charge of 750 young men — to influence change.

Peter Nguura is in charge of Amref’s campaign to end FGM. He sees it as a gross and severe human rights abuse.

“It leads to infertility, we have birth complications meaning that their children die when they are giving birth. And the other part is economic, the women are denied opportunities, they are denied education, because immediately after female genital mutilation, the girls are treated as mature and they are married off at 8 years, at 10 years, at 15 years [of age]. … They don’t finish school, so they are not economically empowered to contribute or even to help their households," Nguura says.

"It's a terrible, terrible evil in the 20th century, it should have ended,” he adds.

James Leiyan is a Maasai warrior, also known as a "moran," who attended one of Ole Lelein's recent training sessions. He says he couldn't prevent his wife from undergoing FGM, but that his daughter will have a different experience.

“When it was time for me to get a wife, I told my father that I did not want my wife to go through FGM. He was furious and said that I was going against tradition. I ran away from home for two weeks, hoping my father would change his mind but he didn’t. I got desperate and went back home and had to accept my father’s wishes. So my wife has gone through FGM. I wish this was not the case, but I will make sure my daughter does not go through FGM,” he says.

“These young men are of marrying age," Ole Lelein says. "So it's important to educate them on the benefits of marrying a girl who has not gone through FGM. They are also the ones who make decisions about the circumcision of their children so they are key in fighting against this practice. In short, they are among the main decisionmakers in our community.”

Ole Lelein also makes home visits to reach more men. But there are limits to his influence. While visiting Jeremiah Ormoi, he meets Ole Tianda. (The prefix "ole" means "son of," and is commonly added to names here.) Even though he is just 27, Ole Tianda is as adamant as some of the elders are that FGM should continue.

"This act is part of our culture and we should not do away with it. I have been to training fighting this practice, but I still feel that it should go on because it is part of our culture,” he says.

Ole Lelein also has to deal with the fact that he is a man campaigning against a practice widely considered a women’s affair. But he says he won’t give up.

“Some people say to me: Don’t you have something better to do than to get involved in women's issues? They say I should be protecting our cultural practices. But I still carry on because I know I am doing the right thing.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated Ole Tiana's age incorrectly. He is 27.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!