Why Ukraine’s newest Holocaust memorial is so important

Visitors to the new Space of Synagogues memorial place stones in remembrance of the dead in Lviv, Ukraine on Sept. 4.

Eli Brauner rarely makes it to the western Ukrainian city of Lviv. When he does, it’s a painful experience for him.

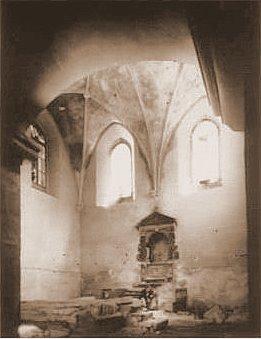

His ancestors built a synagogue here in the late 16th century, believed to be the country's oldest partially preserved synagogue.

After the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, they burned the Golden Rose almost entirely to the ground.

“It’s not easy to be here,” says Brauner, an Israeli researcher who was born in Germany after World War II. “It’s a beautiful city, but also a graveyard for 150,000 Jews.”

Today, a new memorial stands near the remains of the Golden Rose, commemorating Jewish suffering in a city where the thriving prewar community was wiped away.

“I don’t know any other project for conserving Jewish heritage in Ukraine that was financed by a local municipality and also includes international partners and philanthropists,” says Andriy Moskalenko, Lviv’s deputy mayor for development.

Unveiled last Sunday and named The Space of Synagogues, the memorial comes during a time when Ukraine is both sorting out its national identity and attempting to commemorate its Jewish past.

Neither has been straightforward. Officials have come under criticism for glorying controversial nationalists who fought for Ukrainian independence but were also involved in attacks against Jews and Poles.

Lviv, in particular, is a place where the two notions clash. For centuries, the city was a hub of Jewish life and faith, and home to 100,000-200,000 Jews before World War II. It was also the center of Ukraine’s national revival, and remains a bastion of Ukrainian culture. Heated debate between local and international scholars continues to rage over the role local nationalists played in wartime pogroms.

Read more: A synagogue is born in a little Polish town, but no Jews are left

But those involved in Lviv’s memorial say it’s an important step toward overcoming community boundaries and commemorating the sheer scope of the tragedy.

Today, there is almost no local Jewish community to speak of. There's just one functioning Jewish temple. Before World War II, there were about 100. The 2001 census counted 1,900 Jews in Lviv, 0.3 percent of the city’s population — in contrast to roughly one-third before the war. (The census results page includes Jews on a list of "nationality and ethnic groups" in Ukraine with groups like Poles, Russians and Ukrainians.)

The memorial project took eight years and was funded by the city, the German international development agency, GIZ, as well as private sponsors.

Observers say the memorial nudges local visitors to reflect on a little talked-about piece of history: the sudden and tragic disappearance of a community that once played a major role here.

“It’s about signaling a story of absence, while also telling a story of presence,” says Sofia Dyak, director of the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe, a local non-profit that helped coordinate the project.

Not everyone agrees with the memorial, though.

A local Jewish activist has frustrated both local officials and planners with his staunch opposition to the project, arguing the synagogue should be rebuilt in its entirety. While planners haven't ruled that out, it would be an expensive endeavor that is unlikely to happen.

Instead, they’re are hoping to develop a plot adjacent to the memorial that was the site of the Great City Synagogue, built after the Golden Rose. Plans to preserve a local Jewish cemetery are also in the works, partly with help from Brauner’s group, the Association for the Commemoration of Lviv Jewish Heritage Sites. Much like the Golden Rose before the memorial was built, the centuries-old site is in ramshackle conditions with few traces of its original use.

“It will take time,” he said, “but if we unite … we can do it.”

Dan Peleschuk reported from Lviv, Ukraine.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!