Historians disagree on whether ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ is racist

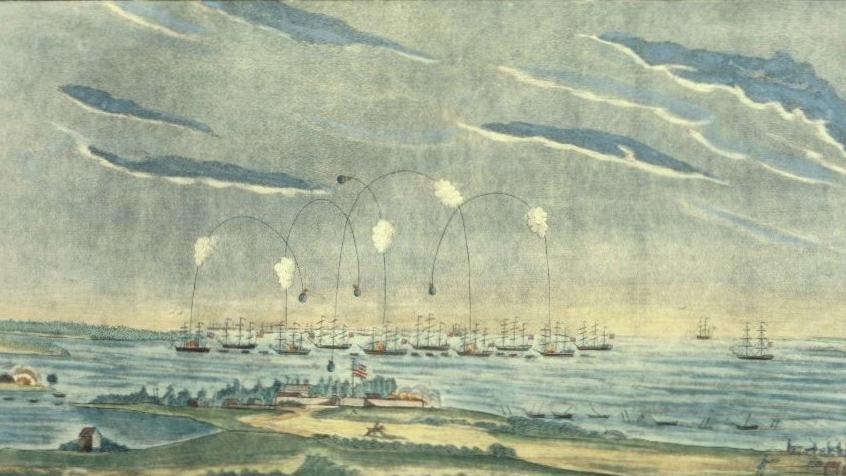

The British attack on Ft McHenry, 1814

The decision of San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick to stop standing for the national anthem has provoked a lot of debate, to say the least. It’s also re-opened a discussion about whether "The Star-Spangled Banner" is actually racist.

Francis Scott Key wrote his famous poem, "The Defence of Fort McHenry," after witnessing the failure of the British assault on the fort, which guarded Baltimore during the War of 1812.

Key wrote four verses. The argument about racism centers on his little-known third stanza:

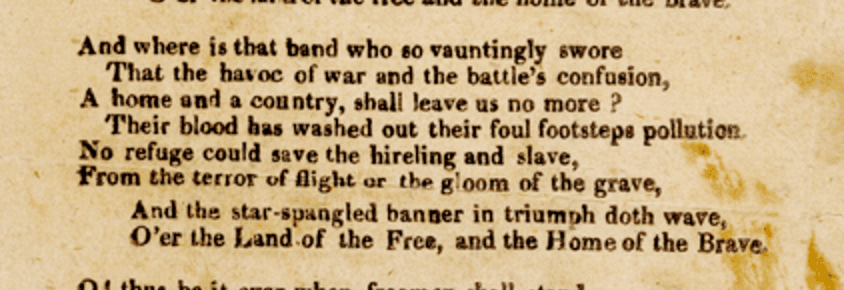

“And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave,

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave.”

The language is definitely archaic and seems a little confusing unless you know the context.

“Essentially,” says writer and academic Jason Johnson, “Francis Scott Key was happy to see former slaves, who had joined the British as part of their Colonial Marines, getting slaughtered and killed as they attempted to take Baltimore.”

Johnson is an associate professor at Morgan State University in Baltimore, and has a piece in online magazine The Root on this issue.

“So it’s clearly racist; it’s clearly pro-slavery, but it’s pretty much in line with the kind of man that Francis Scott Key was.”

Key was a typical white Marylander of his time, and he favored slavery.

About 6,000 African Americans fled to the British during the War of 1812, on the promise of freedom. Most of the men were recruited into the Royal Navy or into the Colonial Marines, a mostly black unit, which fought with distinction.

“It was an amazing opportunity for African Americans to fight for their freedom,” says Johnson.

Many historians agree with Johnson, but some disagree. They point out that Key never told anyone what he actually meant, and some historians interpret his mention of hirelings and slaves to reference all of the invading British forces.

They say it echoes similar rhetoric used since the Revolutionary War to describe the forces of the king of England, especially those units purchased from German princes. American writers contrasted these miserable hirelings and slaves with the virtuous all-volunteer citizen armies of America.

However, Johnson counters that argument. He points out that Key himself faced the black Colonial Marines in battle. His unit was beaten and humiliated by them.

“His troops were slaughtered so aggressively,” Johnson says, “that he had to run home and hide in Washington DC. … So this was personal for him."