When a place has been besieged for years and hunger stalks the streets, you might have thought people would have little interest in books. But enthusiasts have stocked an underground library in Syria with volumes rescued from bombed buildings — and users dodge shells and bullets to reach it.

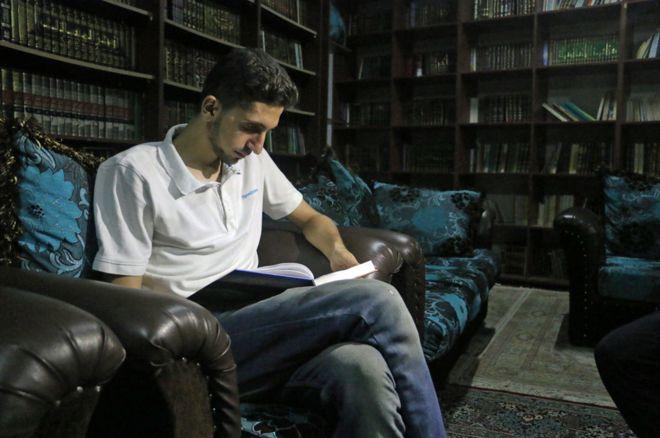

Down a flight of steep steps, as far as it's possible to go from the flying shrapnel, shelling and snipers' bullets above, is a large dimly lit room. Buried beneath a bomb-damaged building, it's home to a secret library that provides learning, hope and inspiration to many in the besieged Damascus suburb of Darayya.

"We saw that it was vital to create a new library so that we could continue our education. We put it in the basement to help stop it being destroyed by shells and bombs like so many other buildings here," says Anas Ahmad, a former civil engineering student who was one of the founders.

The siege of Darayya by government and pro-Assad forces began nearly four years ago. Since then Ahmad and other volunteers, many of them also former students whose studies were brought to a halt by the war, have collected more than 14,000 books on just about every subject imaginable.

Over the same period more than 2,000 people — many of them civilians — have been killed. But that has not stopped Ahmad and his friends scouring the devastated streets for more material to fill the library's shelves.

"In many cases we get books from bomb or shell-damaged homes. The majority of these places are near the front line, so collecting them is very dangerous," he says.

"We have to go through bombed-out buildings to hide ourselves from snipers. We have to be extremely careful because snipers sometimes follow us in their sights, anticipating the next step we'll take."

At first glance the idea of people risking life and limb to collect books for a library seems bizarre. But Ahmad says it helps the community in all sorts of ways. Volunteers working at the hospital use the library's books to advise them on how to treat patients; untrained teachers use them to help them prepare classes; and aspiring dentists raid the shelves for advice on doing fillings and extracting teeth.

About 8,000 of Darayya's population of 80,000 have fled. But nobody can leave now.

Since a temporary truce broke down in May, shells and barrel bombs have fallen almost every day. For the same reason, it's long been impossible for journalists to enter Darayya, so I have been conducting interviews by Skype — my conversations repeatedly interrupted by shattering explosions, so loud that they distort the studio's speakers.

The location of the library is secret because Ahmad and other users fear it would be targeted by Darayya's attackers if they knew where it was.

As it is, the library is in an area considered too dangerous for children to approach. One young girl, Islam, tells me that she spends almost all her time indoors, playing games to help her ignore the gnawing pangs of hunger in her stomach and reading library books she is given by friends.

She tells me she has no idea about the cause of the bloodshed around her.

"All I know is I'm just being fired at," she says.

"I'll be sitting by myself, watching some place being shelled and I'm thinking, 'Why are they bombing this place?' Sometimes I hear that someone has died because of their injuries and I ask myself, 'Why did he die, what did he do?' I don't know."

There is one child who visits the library every day, however, because he lives next door. For 14-year-old Amjad it is safer there than being above ground, and over time his enthusiasm for the place has earned him the role of "deputy librarian.""Shakespeare's style of writing is simply beautiful. He describes every single detail so vividly that it's like I'm in a cinema watching a film in front of me. To be honest I became so obsessed with Hamlet that I began reading it at work. In the end I had to tell myself to stop!"

But, I ask him, in a besieged town that has only had access to two aid convoys in nearly four years, wouldn't it make more sense for the library enthusiasts to spend their time looking for food rather than books?

"I believe the brain is like a muscle. And reading has definitely made mine stronger. My enlightened brain has now fed my soul too," he replies.

"In a sense the library gave me back my life. It's helped me to meet others more mature than me, people who I can discuss issues with and learn things from. I would say that just like the body needs food, the soul needs books."

It turns out that even the greatly out-gunned Free Syrian Army fighters, who have the daunting task of defending the town, are avid readers.

"Truly I swear the library holds a special place in all our hearts. And every time there's shelling near the library we pray for it," says Omar Abu Anas, a former engineering student now helping to defend his home town.

Every time he heads for the front line, he stocks up with books first. Once there he spends much of his time with a rifle in one hand and a book in the other.

"In the heart of the front line, I have what I'd call a mini library. So I bring a collection of books and I put them there. So I sit there for six or seven hours, reading."

Many of his comrades also have their own mini front line libraries, he says, adding that at just about every defense point, which are spaced about 50 meters apart, you will find a collection of borrowed books.

"So, for example, when I have finished reading a book I go up to one of the others on the front line and exchange it for one he has just read. It's a great way of exchanging ideas as well as books."

Unfortunately for Anas, his fellow fighters and the people of Darayya, they may soon have little time for reading. Over the past two weeks Syrian government forces and their Hezbollah allies have moved into all the farmland around the suburb and even some outlying residential areas.

One man I spoke to predicted that, after nearly four long years of siege, Darayya could fall within days.

For now though, Anas says the library is helping to strengthen the town's defences as well as its resolve.

"Books motivate us to keep on going. We read how in the past everyone turned their backs on a particular nation, yet they still made it. So we can be like that, too. They help us plan for life once Assad is gone. We can only do that through the books we are reading. We want to be a free nation. And hopefully, by reading, we can achieve this."

A postscript, from Tuesday:

This story originally appeared in the BBC News Magazine. Additional research by Mariam el Khalaf.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter and on Facebook.

Down a flight of steep steps, as far as it's possible to go from the flying shrapnel, shelling and snipers' bullets above, is a large dimly lit room. Buried beneath a bomb-damaged building, it's home to a secret library that provides learning, hope and inspiration to many in the besieged Damascus suburb of Darayya.

"We saw that it was vital to create a new library so that we could continue our education. We put it in the basement to help stop it being destroyed by shells and bombs like so many other buildings here," says Anas Ahmad, a former civil engineering student who was one of the founders.

The siege of Darayya by government and pro-Assad forces began nearly four years ago. Since then Ahmad and other volunteers, many of them also former students whose studies were brought to a halt by the war, have collected more than 14,000 books on just about every subject imaginable.

Over the same period more than 2,000 people — many of them civilians — have been killed. But that has not stopped Ahmad and his friends scouring the devastated streets for more material to fill the library's shelves.

"In many cases we get books from bomb or shell-damaged homes. The majority of these places are near the front line, so collecting them is very dangerous," he says.

"We have to go through bombed-out buildings to hide ourselves from snipers. We have to be extremely careful because snipers sometimes follow us in their sights, anticipating the next step we'll take."

At first glance the idea of people risking life and limb to collect books for a library seems bizarre. But Ahmad says it helps the community in all sorts of ways. Volunteers working at the hospital use the library's books to advise them on how to treat patients; untrained teachers use them to help them prepare classes; and aspiring dentists raid the shelves for advice on doing fillings and extracting teeth.

About 8,000 of Darayya's population of 80,000 have fled. But nobody can leave now.

Since a temporary truce broke down in May, shells and barrel bombs have fallen almost every day. For the same reason, it's long been impossible for journalists to enter Darayya, so I have been conducting interviews by Skype — my conversations repeatedly interrupted by shattering explosions, so loud that they distort the studio's speakers.

The location of the library is secret because Ahmad and other users fear it would be targeted by Darayya's attackers if they knew where it was.

As it is, the library is in an area considered too dangerous for children to approach. One young girl, Islam, tells me that she spends almost all her time indoors, playing games to help her ignore the gnawing pangs of hunger in her stomach and reading library books she is given by friends.

She tells me she has no idea about the cause of the bloodshed around her.

"All I know is I'm just being fired at," she says.

"I'll be sitting by myself, watching some place being shelled and I'm thinking, 'Why are they bombing this place?' Sometimes I hear that someone has died because of their injuries and I ask myself, 'Why did he die, what did he do?' I don't know."

There is one child who visits the library every day, however, because he lives next door. For 14-year-old Amjad it is safer there than being above ground, and over time his enthusiasm for the place has earned him the role of "deputy librarian.""Shakespeare's style of writing is simply beautiful. He describes every single detail so vividly that it's like I'm in a cinema watching a film in front of me. To be honest I became so obsessed with Hamlet that I began reading it at work. In the end I had to tell myself to stop!"

But, I ask him, in a besieged town that has only had access to two aid convoys in nearly four years, wouldn't it make more sense for the library enthusiasts to spend their time looking for food rather than books?

"I believe the brain is like a muscle. And reading has definitely made mine stronger. My enlightened brain has now fed my soul too," he replies.

"In a sense the library gave me back my life. It's helped me to meet others more mature than me, people who I can discuss issues with and learn things from. I would say that just like the body needs food, the soul needs books."

It turns out that even the greatly out-gunned Free Syrian Army fighters, who have the daunting task of defending the town, are avid readers.

"Truly I swear the library holds a special place in all our hearts. And every time there's shelling near the library we pray for it," says Omar Abu Anas, a former engineering student now helping to defend his home town.

Every time he heads for the front line, he stocks up with books first. Once there he spends much of his time with a rifle in one hand and a book in the other.

"In the heart of the front line, I have what I'd call a mini library. So I bring a collection of books and I put them there. So I sit there for six or seven hours, reading."

Many of his comrades also have their own mini front line libraries, he says, adding that at just about every defense point, which are spaced about 50 meters apart, you will find a collection of borrowed books.

"So, for example, when I have finished reading a book I go up to one of the others on the front line and exchange it for one he has just read. It's a great way of exchanging ideas as well as books."

Unfortunately for Anas, his fellow fighters and the people of Darayya, they may soon have little time for reading. Over the past two weeks Syrian government forces and their Hezbollah allies have moved into all the farmland around the suburb and even some outlying residential areas.

One man I spoke to predicted that, after nearly four long years of siege, Darayya could fall within days.

For now though, Anas says the library is helping to strengthen the town's defences as well as its resolve.

"Books motivate us to keep on going. We read how in the past everyone turned their backs on a particular nation, yet they still made it. So we can be like that, too. They help us plan for life once Assad is gone. We can only do that through the books we are reading. We want to be a free nation. And hopefully, by reading, we can achieve this."

A postscript, from Tuesday:

This story originally appeared in the BBC News Magazine. Additional research by Mariam el Khalaf.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter and on Facebook.