Let the transition begin

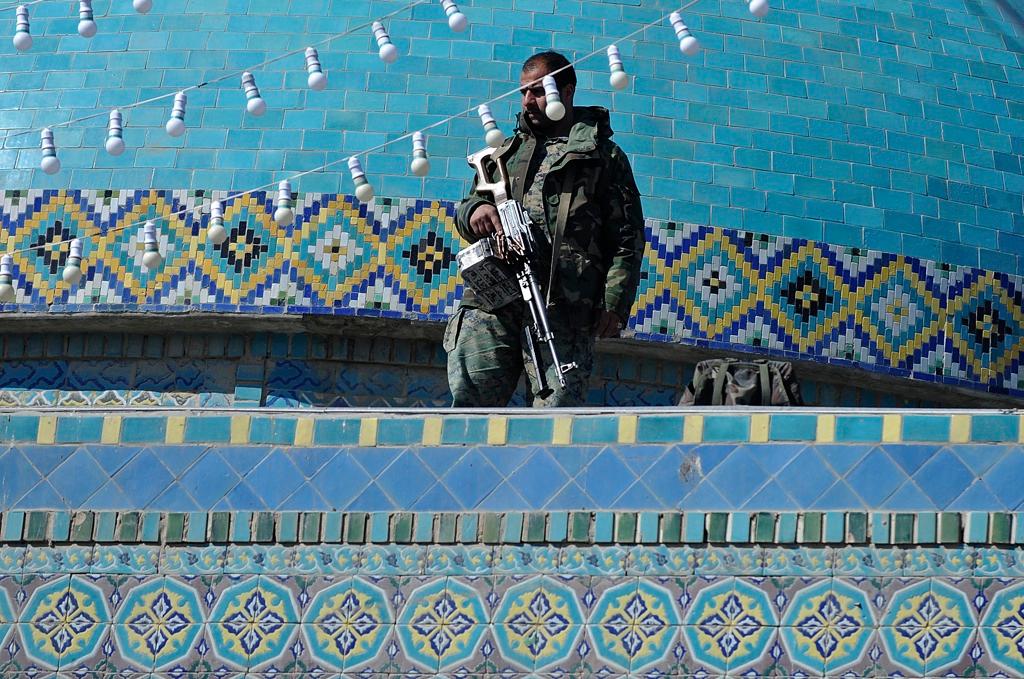

Afghan security personnel prepare for New Year’s celebrations in Mazar-e-Sharif. Mazar will be one of the first cities to be fully secured by Afghan forces.

Afghanistan has just marked Nauroz, the ancient Zoroastrian holiday hailed as the start of the New Year, celebrated by jumping over bonfires and eating a dire combination of newly-sprouted grains called somonak. Young men planning to wed are expected to bankrupt themselves buying gifts for their fiancee’s families.

Everyone consumes a great deal of dried fruits, nuts, and cake. Schools reopen after the long winter break. This being Afghanistan, Nauroz will also signal the beginning of the year’s fighting season. Welcome to 1390.

President Hamid Karzai observed the occasion by delivering his much-anticipated speech on “Inteqal,” or transition, announcing that three provinces and four cities would be handed over to Afghan security forces. Karzai has gone on record as saying that 1390 would be a “year of challenges.” That could well be the understatement of the era – no matter which century you believe it to be. Even the most optimistic assessment of the army and police put them well behind schedule, and the population is more than a bit nervous at seeing the international forces preparing to withdraw.

But the Transition List was chosen wisely – most of the areas mentioned are already among the safest in the country: Kabul, Panjshir and Bamian provinces, as well as the provincial capitals Mazar-e-Sharif, Herat, Mehterlam and Lashkar Gah. But even here there are likely to be hiccups. Past experience has not been felicitous.

Kabul city transitioned to Afghan sovereignty in 2008; the rest of Kabul province will now follow suit – except for Surobi district, which is where the fighting is. In the three years since the Afghan security forces assumed responsibility for the capital, they have had several notable achievements. Just last year seven attackers stormed a shopping center in downtown Kabul.

The police, army and intelligence services were called out, and a prolonged gun battle ensued. All the attackers eventually died – at least three blew themselves up. But it took the combined security forces of Kabul more than five hours to subdue the other four, which they finally did by burning down the shopping center where the attackers were holed up. Hundreds of police, army and other armed troops would not take on the four remaining insurgents in a face-to-face battle. The U.S. Embassy, the United Nations, and assorted other internationals congratulated the Afghans security forces on their handling of the situation.

I suspect that the shopkeepers who lost their livelihoods might have been a bit less enthusiastic. In October, 2009, when a UN guest house popular with election workers was hit in Kabul, the police showed up just in time to make things even worse. Of the five UN staffers killed in the attack, at least one and possibly more were shot by the police, not the Taliban fighters, according to a UN report released several months after the incident.

Mazar-e-Sharif, the booming city in the north, was a brilliant choice for transition. It is the capital of Balkh province, which is headed by a governor so strong and independent that some people refer to his fiefdom, only half-jokingly, as “the Independent Republic of Balkh.” Atta Mohammad Noor, the man in question, is not a warm friend of Karzai’s. During the 2009 presidential elections Atta opposed the president for all he was worth, delivering an impressive victory in Balkh for Karzai’s main rival. Dr. Abdullah. Karzai tried for years to remove him, but later seemed to decide to keep this particular camel inside the tent.

Atta has his own forces who are perfectly capable of dealing with the Taliban. They could also repel the central government if necessary, but that is not being openly discussed. Bamian, the lovely mountain valley that used to be home to the massive 6th-century Buddhas has not been a security problem for the past ten years. Instead, the safe and sleepy province has remained obscure and under-developed, paying what is called in the development world “the Peace Penalty.”

Squeaky wheels, like Kandahar and Helmand, get the most oil – millions have flowed into insurgent-plagues areas in a (usually futile) bid to win hearts and minds. In Bamian, the population has no love for the Taliban, having been the victims of some of the worst repressions of the Taliban era. The bearded fundamentalists were even harder on the local people, mainly Shi’ite Hazaras, than they were on the Buddhas themselves.

But the Transition may not make the people of Bamian happy. One journalist from the area, upon hearing that his province was likely to be on Karzai’s New Year’s transition list, shook his head sadly. Projects funded by the New Zealand-led Provincial Reconstruction Team, he feared, would now be discontinued. “This will mean even less reconstruction money coming to us,” he sighed.

The province has almost no paved roads, little electricity, and a rudimentary economy. The tourist industry is depressed due to the absence of the Buddhas, the presence of landmines, and a dangerous road linking Bamian with the capital, terrorized by insurgents and bandits that prey on unwary travelers. Panjshir has long been a popular day-trip from Kabul – two days if you decide to hike up into the emerald mines to try your luck at hacking a priceless gemstone from the rock walls.

It was the birthplace of the legendary Ahmad Shah Massoud, scourge of the Taliban and the Soviet forces, at least in popular imagination. Panjshiris have a reputation for fierce fighting, and an almost allergic reaction to the Taliban. Lashkar Gah, capital of Helmand, may seem a bit edgier. The Taliban have attacked the city directly several times.

But surrounding Lashkar Gah are thousands and thousands of U.S. Marines, who are beating back the Taliban in Nawa, Sangin, and assorted other battle zones. The Taliban would have to cut through them to reach the city. Out-gunned and out-manned, they will most likely lie low until the U.S. troops are withdrawn. Herat, the jewel of western Afghanistan, is still reaping the benefits of its prime location and the tender attentions of its erstwhile governor, Ismail Khan.

Khan collected taxes from the ample trade running across the border from Iran and Turkmenistan and used the proceeds to make Herat one of the most developed cities in the country. Herat had 24-hour electricity when Kabul was still freezing in the dark; on one trip an Afghan journalist looked at the streetlights in wonder.

“They keep them on even during the day,” he said. “I’m moving here.” The population is mostly Dari-speaking, non-Pashtun, and opposed to the Taliban on principle. Mehterlam, the capital of Laghman province, has been relatively quiet – but it lies in a volatile area, and may be the one real test of the mettle of the Afghan security forces. Happy New Year. Let’s hope we all make it to 1391.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!