Zimbabwe not ready for free and fair election

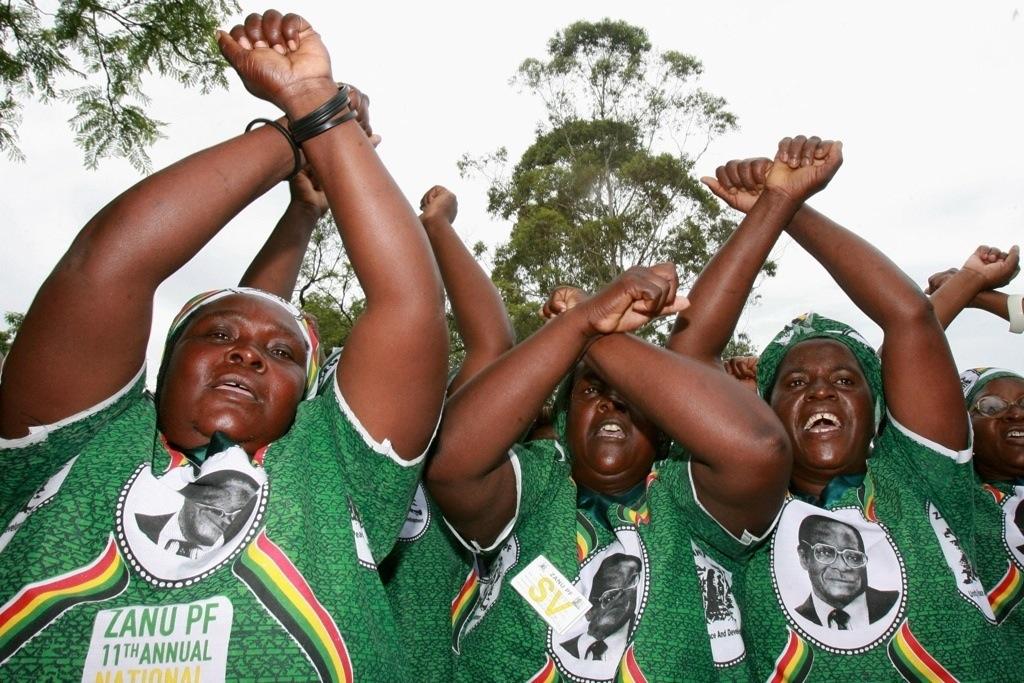

Supporters of Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe’s ruling ZANU-PF party have been able to inflict violence on the opposition with impunity. South African President Jacob Zuma says that Zimbabwe is not prepared for fair elections. Yet Mugabe has said he will hold elections this year.

HARARE, Zimbabwe — Most Zimbabweans seem to think that elections will help resolve the sharp differences among political parties in this polarized country.

But there is little likelihood of that.

President Robert Mugabe, 87, and his Zanu-PF party have declared they want elections later this year or, failing that, early next year.

Morgan Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) and the smaller MDC faction headed by Welshman Ncube say conditions are not right for elections. The voters’ roll is a mess, a new constitution must be drafted, broadcasting remains in Mugabe’s iron grip and no serious attempt has been made to reconcile differences between the main political players that form the power-sharing government.

A violent fracas in parliament is the latest example of Mugabe's refusal to allow basic democratic freedoms and even-handed protection of the law for all.

Mugabe ally and senior minister Didymus Mutasa declared that Zanu-PF would protect an unruly mob that invaded parliament last week and assaulted an MDC MP and journalists who had met to discuss human rights legislation.

“We will defend them, they are our members,” Mutasa said. Those who were beaten up “must have provoked” the Zanu-PF activists, said Mutasa, who had earlier defended generals who said they would not work under a Tsvangirai government.

More from GlobalPost: Why is Zimbabwe's national airline called Scare Zimbabwe?

It is incidents like this that have convinced South African President Jacob Zuma, who is the facilitator of on-going negotiations between the Zimbabwean parties, to declare that insufficient progress has been made in establishing the conditions for free and fair elections.

These conditions were laid out in 2009 when South Africa and other neighboring countries brokered Zimbabwe's government of national unity, which yoked Mugabe and Tsvangirai together in a power-sharing government. That government has proved to be unworkable and Mugabe has retained virtually all the power. But now Zuma and other regional leaders are taking a hard, critical stance. Zuma's statements that elections are impossible this year have infuriated Mugabe.

Mugabe's vitriolic approach is reflected in articles in the state media by his former information minister, Jonathan Moyo. Moyo has been using intemperate language to denounce Zuma and his international affairs adviser Lindiwe Zulu. Moyo has also branded the U.S. ambassador to Zimbabwe an "Uncle Tom.”

Ignoring the obvious point that Mugabe is biting the hand that feeds him, the veteran Zimbabwean leader is blocking progress on economic reform and eroding regional support, which is fast dissipating. It is significant that at recent regional summits held this year in Livingstone, Zambia, and Sandton, South Africa, Zuma has taken seriously Tsvangirai’s complaints of human rights abuses and charges that Zanu-PF is refusing to implement agreed-upon reforms. Even further, Zuma appears to have dismissed improbable counter-claims by Zanu-PF that the MDC is causing the violence.

Mugabe has struggled — unsuccessfully — to get the minutes of those meetings changed so that his party will look like the victim of MDC machinations. Zuma has understandably refused to comply with this subterfuge.

This reflects a seismic political shift in southern Africa's politics. Until recently Mugabe has been able to click his fingers and get regional leaders into line behind him. But now he is now seen to be floundering as fissures emerge in the once solid bloc of the Southern African Development Community, which groups together the 15 nations of southern Africa.

There is a bigger picture here which should worry regional leaders. Zimbabwe is divided. Mugabe represents the old thinking of nationalist leaders who can’t let go of their illusions. That includes the belief that the country belongs to them and therefore entitles them to plunder resources and occupy posts from which to exercise patronage. Mugabe has done nothing to tackle corruption and surrounds himself with ministers who have become very rich, very quickly. Zimbabwe has suffered as a result.

The other side is represented by a new generation of Zimbabweans who value accountability and good governance. For them the liberation war of the 1970s is a distant memory and they hold in scorn Mugabe’s gang of generals and policemen who preside over his totalitarian state structure. They also refuse to buy Mugabe's discredited nationalist mantras.

Observers say they are encouraged to see an African country in which a younger generation is unimpressed with the pretensions of a corrupt governing class. But without the assistance of that class, particularly the military, it will be difficult for Tsvangirai to govern. He cannot succeed without the cooperation of the generals who daily denounce him.

The generals have the power to block reform and they routinely state their determination not have any collaboration with the MDC.

More from GlobalPost: Zimbabwe voters' roll is a shameless shambles

So it is serious when the Mugabe government refuses to take action over the violence in parliament. After calls for his removal when he failed to lift a finger after the invasion of the House of Assembly, police chief Augustine Chihuri this week was unrepentant: “When a mad man shouts you do not shout back … I will not be told what to do by sellouts and puppets.”

The fracas in parliament could be dismissed as a minor political dust up. But it is emblematic of Mugabe's fundamental refusal to even-handedly enforce the law. In the 2008 elections, some 300 opposition members were killed and thousands more beaten and tortured by Mugabe's police and militia. Few, if any, of the perpetrators were brought to justice. The elections were fatally skewed by the violence and it resulted in the ineffective power sharing government. So far Mugabe and his generals have retained the upper hand.

But nothing stays the same, especially in politics.

South Africa's white generals said they would never take orders from a black president in 1994 as they contemplated blocking the transition to democracy. Yet within months they were saluting Nelson Mandela.

Recent events in Malawi, where thousands took to the streets to denounce President Bingu wa Mutharika’s authoritarian rule, suggest the "Arab Spring" tide of political change is steadily rolling south.

Resistance is to be expected and Mugabe and his generals clearly have a few cards up their sleeves. But with a newly critical South Africa calling the shots and if Zimbabwe's opposition can hold together, Robert Mugabe may be forced to loosen his iron grip on Zimbabwe.

More from GlobalPost: From vaginas to pap smears: Zimbabwe women blog

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!