Introduction: Asia’s bloodiest insurgency

Illustration by Antler.

PATTANI, Thailand — Dawn smolders above this seaside city in Thailand’s southern borderlands. Troops already occupy the streets in force. Skinny conscripts with assault rifles patrol through the fog. German Shepherds sniff for bombs in the brush.

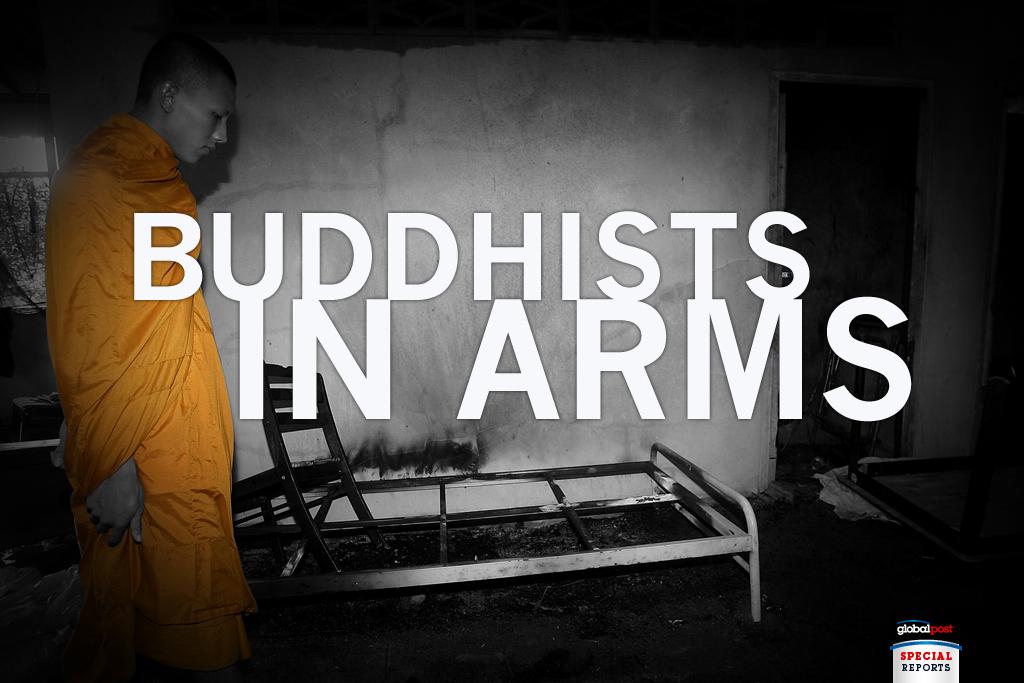

This is the hour of paranoia. Come mornings, gunmen slip through curtains of jungle foliage lining the roadside. They kill cops. Army officers. Teachers traveling to class. Kids sometimes. To stoke maximum horror, they decapitate Buddhist monks with machetes.

(Read More: Part 1 – How did insurgents master bomb-making?)

As oblivious backpackers party up the coast, an Islamic rebellion roars on with no end in sight. The attackers’ prey? In local jihadi parlance, “Siamese infidels” and their “Muslim running dogs.” In lieu of familiar screeds against Jews, Christians and the “Great Satan” America, these mujahideen call for the heads of Thai Buddhists.

Islamic guerillas here vow to wrench free a Connecticut-sized chunk of Thailand and create the world’s newest Islamic state. With Muslim separatist movements in the Philippines and Indonesia largely tamed through peace agreements, this Islamic insurgency is now Asia’s bloodiest.

“We used to know the Muslims,” said Penporn Saikaew, a 60-year-old Buddhist grandmother living in an army-designated “red zone” rife with insurgents. “We went to the same schools. We loved each other.”

“It’s not like that anymore,” said Penporn, who totes a .38-caliber Smith and Wesson when she leaves the house. “We don’t trust them. And they don’t trust us.”

Known to Thais as the “deep south,” this region was once an Islamic sultanate called Pattani. Along with much of the Malay-Indonesian archipelago, the region absorbed Islam from 13th-century Arab traders. Meanwhile, Buddhism took root in the Siamese empire to the north.

The sleepy sultanate existed for about 500 years until the turn of the 20th century, when it was swallowed by Siam (now Thailand) and carved into three provinces: Yala, Narathiwat and Pattani. The region, roughly 85 percent Muslim, is still largely governed by ethnic Thais, a 15 percent minority.

But Muslims here have never fully assimilated into the so-called Land of Smiles. From the beginning, separatists have kicked and screamed for an end to “Siamese occupation.”

Independence campaigns sparked and fizzled in the 1900s. Only in the last decade has the insurgency broken into a wild sprint, its renaissance waged by a new wave with a flair for shock violence.

But so far, the jihadis have managed to escape much Western intrigue. Even as tourists flock to crystal-sand beaches a few hours’ drive north. Even as Thailand’s counterinsurgency is assisted, at arm’s length, by the U.S. military. Even as the death toll climbs towards 4,700 and insurgents’ bomb skills approach Hurt Locker-caliber expertise.

“If we leave Iraq and Afghanistan off the list, the southern region of Thailand is one of the most violent insurgencies in the world,” said Srisompob Jitpiromsri, director of the insurgency monitoring group Deep South Watch. “And we seem to be moving towards a worse situation.”

(Read More: Bullet scarred and tourist ready, re-opening after Thai-Cambodia conflict)

Killings occur at a daily clip. Ethnic Thais have fled en masse. The hardened core that remain have assembled all-Buddhist militias composed of men and women, teens and the elderly. Their temples, a favored jihadi target, have become fortresses ringed with sandbags and razor wire.

Now, for the first time since the insurgency’s 2004 renaissance, Thailand’s political leadership is openly uttering a once-forbidden phrase: “special administrative zone,” code for ceding more autonomy to Islamic Thailand. Military officers begrudgingly admit to “peace talks” with the shadowy network that has murdered thousands of troops, cops and civilians.

“Independence is our demand and it will not be broken,” said Kasturi Mahkota, a senior leader with one of the insurgency’s original factions, the Pattani United Liberation Organization. Through its broader mujahideen network, the group claims to command 80 percent of insurgent attacks.

“You can see the case of Palestine, which got some autonomy and dropped their true fight for independence. Not us,” he said. “We fight for peace. But to get peace, sometimes you need a little violence to get peoples’ attention.”