Highway 15: The long road to rehabilitation

The village of Hezna, Saudi Arabia.

HEZNA, Saudi Arabia – Turn off Highway 15 near the city of Al Baha and a narrow, winding road brings you up a steep hill to an outcropping of huge boulders and beautiful, rugged terrain where this village lies.

Hezna is a typical tribal enclave for the southwest of Saudi Arabia with its sweeping views and cool breezes.

Osama bin Laden, a native of the Saudi southwest, knew this area well, and his family had through generations woven together relationships with the prominent tribes that hail from here.

It was in the village of Hezna that bin Laden’s Al Qaeda recruited three young men for jihad and sent them to Afghanistan for training and then on to America to carry out the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

A total of twelve of the 15 Saudis among the 19 hijackers came from the leading tribes in the provinces that are strung along Highway 15, which runs through here and which was built in the 1960s by bin Laden’s father whose construction company was close to the House of Saud.

That fact led me to a journey down Highway 15 ten years ago when I was the Middle East bureau chief for The Boston Globe and we were trying to understand the profile of the young men who carried out the attacks.

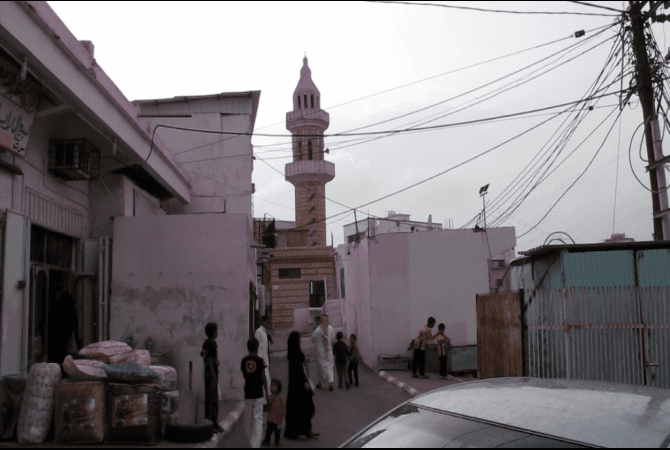

On that trip, I spoke to friends and family of the hijackers and to young people many of whom expressed support for bin Laden. I heard the fiery sermons of the imams of the Wahhabi clerical establishment echo from the minarets of mosques. I visited public schools where I saw first hand the boring, rote lessons — and sometimes hateful, anti-Western messages — of teachers steeped in the same puritanical ethos of Wahhabism.

Now on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, I returned to this small village to find the family of Ahmed Al Haznawi, one of the hijackers who was aboard United Airlines Flight 93 when it crashed in rural Pennsylvania. Twenty-two years old at the time, he was widely considered the head of the triangle of youths from here who joined bin Laden’s 9/11 plot. I wanted to see if ten years on, I might be able to gain more understanding into the forces that led Haznawi and the other hijackers from here to embrace the Apocalyptic ideology of Al Qaeda and take part in the worst attack on American soil since Pearl Harbor.

It seemed to me that after ten years we still did not have a clear picture of why the attacks have so many links back to Saudi Arabia. Not just that bin Laden himself hails from a Saudi family closely connected to the palace and that 15 of the 19 hijackers were Saudi, but there remained deeper questions about how the Wahhabi religious establishment and the educational system over which it presides had provided fertile soil for fierce anti-Americanism and a youth culture that answered a call to ‘jihad.’

I remembered where the Haznawi family compound was near the top of the hill and went there on an afternoon in late June. Haznawi’s father, Sheikh Ibrahim Al Haznawi, is still the head of the mosque in the old marketplace of the village. The Haznawi family is a branch of the large and respected Alghamdi tribe, which numbers as many as 200,000.

When we went to the Haznawi family home, we were not permitted to enter the gate. I turned back down the road toward he mosque by the old market place and I met up with Amin Hamid Alghamdi, who is a teacher.

He remembered giving Koranic lessons to Haznawi and the other two young hijackers who hailed from a nearby village in the province. He said their understanding of Islamic principles were misguided and it was clear in the years before they left to join Al Qaeda and train in Afghanistan that they were being influenced by radical Islamic clerics whose audio tapes were widely circulated in those days.

Amin, the teacher, knows the families very well and offered to help me speak with them by phone. We called Hamzawi’s father, and Amin put his cell phone on speaker as my interpreter translated from Arabic to English.

There was fury in the father’s voice. Ibrahim Hamzawi said he refused to meet with anyone who was American. And he berated America for its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and, he said, for the taking of many more civilian lives than were taken on the morning of September 11th.

“I will not see you or answer your questions. Why should I when I have so many questions for you?” he asked. “America is the first enemy of all Muslims. Why? Why are Americans attacking and killing Arabs and Muslims. All of this is because of Israel. Why can’t you control your Jewish lobby which is directing your foreign policy?”

Amin Hamid Alghamdi. |

His rant went on crackling with hatred over the speakerphone.

Through the translator, I asked him if what his son did was wrong.

He replied, “I am proud of my son as is all his family.”

Family and friends who I interviewed ten years ago said Haznawi played off tribal loyalties to bring two distant cousins from the village of Beljurashi — Ahmed, 26, and Hamza Alghamdi, 21 — into jihad and ultimately into the 9/11 plot. They were both among the hijackers on United Airlines Flight 175 when it crashed into the south tower of the World Trade Center.

I came looking for answers, but the kingdom is as opaque today as it was ten years ago. It’s still difficult to get to the bottom of the young lives of the men who did the hijacking. Their lives remain largely undocumented and the details of the forces that pulled them together are still largely unknown.

In the six months following 9/11, Saudi authorities arrested 639 young men suspected of militancy, many of them from this region. They were thoroughly interrogated and many were then released. Some remain in prison. The government refuses to reveal any findings of a top secret, 600-page report it undertook on Islamic militancy in the kingdom, the 15 young Saudi hijackers and how they were recruited.

Dr. Abdulrahman Al Hadlaq, General Director of the Interior Ministry’s Ideological Security Directorate, helped to assemble the findings of the report, but said it remains classified.

“It was so important to understand the roots of the problem,” he said in an interview at a private club for security officers in Riyadh.

GlobalPost Correspondent Caryle Murphy and I sat with him drinking tea in the plush environs of the club surrounded by stuffed wild animals and large romantic oil paintings of the desert kingdom and its tribal culture. We peppered him with questions and he provided mostly polite, diplomatic answers which mostly turned the conversation to the hard work that he said Saudi Arabia has done to confront religious extremism and militancy.

Al Hadlaq is at the center of an effort in Saudi Arabia to try to rehabilitate extremists, a program that by some accounts is working. He said there were about 11,000 Islamic militants who they’ve arrested, about half of whom have been released and half of whom pose a threat and need what he calls “rehabilitation.”

“We have the ability to rehabilitate them. We don’t have a 100 percent guarantee it will work for all. But when you compare it to recidivism rates for other crimes, such as drug abuse, which is about 60 percent, we are at around 10 percent,” he said.

He recognized that there have been notable failures in which extremists have gone through rehabilitation only to end up in neighboring Yemen as part of a new permutation of Al Qaeda.

But he quickly added, “The Saudis are doing many things. When we have a problem, we deal with it.”

The immediate families of the hijackers have been instructed to never speak to the media, and ten years ago my ability to reach them for even a few brief comments was only possible through an intermediary by phone or through a crack in a compound gate, just at it was on this trip.

After listening to the father’s angry tirade against America and ultimately his pride in his son’s role in the September 11th attacks, we tried to reach other family members. It’s not easy in a place like Saudi Arabia to do that.

But the teacher, Amin, did help to put me in touch with Khaled Alghamdi, 40, the brother of hijacker Said Alghamdi. And Khaled had a very different answer to the same question I had put to the father. Did he think that what his brother did was wrong?

“Yes,” he replied in Arabic, speaking through the translator. “What my brother did was wrong.”

And he said with great sadness in his voice, “I miss my brother. I miss him the same way Americans miss their loved ones killed on 9/11. It was useless violence.”

After we hung up the phone, I spoke at length with the teacher, Amin, who was educated and gentle in the way he spoke and patient in trying to help me find answers to so many questions.

Amin explained, “There are two sides of remembering September 11th here and you’ve heard both of them from two families. There is sadness which you heard from the brother. And there is emotion and anger. That came from a father who is missing his son. He’s human.”

Then he began carefully drawing for me a diagram on the back of a piece of paper he found in his car. He was trying to sketch a chart with pillars that represented the core of Islam and then crossing lines that illustrated how the beliefs of the three young hijackers contradicted the faith. They were lessons lost on his former students, but Amin is still teaching.

(This work was supported by a 2011 Knight Luce Fellowship for Reporting on Global Religion. The fellowship is a program of the University of Southern California's Knight Program in Media and Religion.)

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!