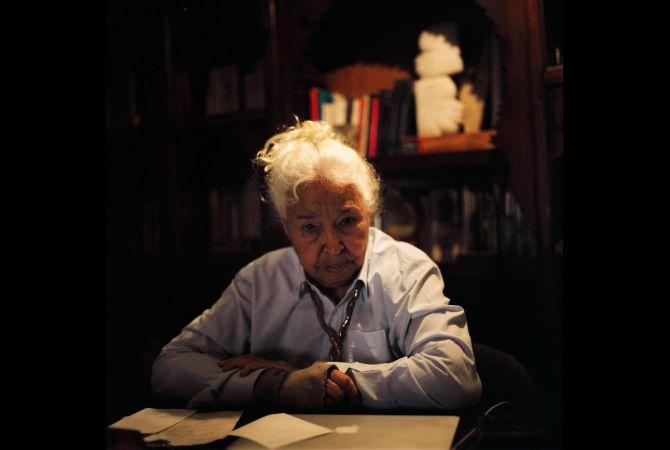

The Pioneer: Nawal El-Saadawi

Nawal El-Saadawi, a prominent Egyptian feminist and revolutionary.

CAIRO, Egypt — In a small village outside Cairo in the early 1940s, a little Egyptian girl sent God a message.

“I wrote a letter to God and told him: ‘Dear God: Why you prefer my brother to me?” recalled famed writer and feminist Dr. Nawal El-Saadawi. “'If you are not just, I am not ready to believe in you.’”

“That,” she said, “is radicalism.”

El-Saadawi is a career dissident and renegade author. Now 80, she has aged with character and resembles something of a caricature — short, petite body; broad, heart-shaped face; and a large head crowned by a swath of puffy, white Einstein-esque hair.

“All my life I was revolting,” she said, ticking off a string of Egyptian rulers. “Against King Farouk, against [Gamal Abdel] Nasser, against [Anwar] Sadat, against [Hosni] Mubarak.”

But today, El-Saadawi is bored. She couldn’t even muster the interest to run for parliament again, despite it being the freest such vote in Egypt’s modern history. Her failed 2005 election was “impossible,” she said approvingly, explaining that it was “creative, at that moment, to be against Mubarak."

“But this election is possible,” she said dismissively. As for overthrowing a dictator? El-Saadawi has moved on.

Now she’s calling for a counter-revolution in Egypt, be it by protesting in Tahrir Square or holing up in an obscure village to work on her latest book, as she intended to do the day after speaking with GlobalPost.

More from GlobalPost: Egyptian women challenge abuses, military

Writing is revolutionary for El-Saadawi because she sees her work as intimately tied to the lives of her restive fellow Egyptians.

“Creativity abolishes the line between the self and the other,” she said, a line she probably used while teaching courses on “Dissidence and Creativity” in the United States after persecution forced her to flee Egypt in 1988.

El-Saadawi penned a number of works during her eight-year exile in the West. The Arabic novel she’s working on now would bring her list of published work to a total of 18 books, plus eight collections of short stories and three plays, a colossal output the author described as a labor of love — literally.

“The pleasure of writing, to me, is more than sex,” she said, squinting happily from behind her sprawling writing desk and encircled by a mass of books ranging from The New Testament to "Dope Inc." and "The Sex Game."

El-Saadawi’s passion for writing doesn’t means she’s not interested in sex itself, however, two of her most controversial Arabic-language books being "Women and Sex" (1969) and "Men and Sex" (1973). The works were groundbreaking for conservative Egyptian society at the time, helping shape a nascent feminist movement now extremely active in Egypt’s civil society.

But unlike some feminists, El-Saadawi refused to attribute challenges facing Egyptian women to the whole ‘men hate women’ equation.

“As if,” she said, “the problem is that it’s a matter of genital organs.”

“It’s a matter of capitalism,” she argued. “Capitalism. Class oppression. Gender oppression. Religious oppression. Race oppression, and all that. It’s not a matter of ‘a man hates me‘ — you can have a lover, a man who loves you and he’s true [to you].”

“Some men are less patriarchal than women,” the thrice-married author went on. “So it’s a matter of, what’s in your mind? What’s your struggle? Are you really struggling for equality, justice, freedom? Are you doing that, on the personal level, in your home, outside, everything?”

“Are you going to change the world? I say yes. That’s my impossible. I believe in the impossible.”

The woman has lived the impossible.

“I was about to be killed all my life,” she said. Her name was featured on death lists under previous regimes. Also an accomplished physician, El-Sadaawi was kicked out of her job as the general director of the Ministry of Health’s public health division — a position she held for 14 years, until 1972 — for speaking out about female genital mutilation, a controversial practice that remains common in Egypt today despite being widely denounced by rights groups. Then she was run out of her own country.

For a lifetime activist like her, the key to rebelling against the system — whether it be against patriarchy or against a political leader like Mubarak — is courage. The most important thing for today’s protesters, she said, is being able to “trust yourself.”

That’s why El-Saadawi believes another major uprising is possible in Egypt today. The “fear is lost” now, she said, and “the counter-revolution is working very hard.”

El-Saadawi harbors similar hopes for uprisings around the world, actively supporting Occupy Wall Street demonstrations in both New York City and London. The towering opposition figure has embraced globalization, taking her activism international in a move that sets her apart from other Egyptian activists focused primarily on the region.

Her sympathy for such movements goes way back. In Memoirs From The Women’s Prison (1983), she wrote something that now sounds like it comes straight out of an Occupy Wall Street handbook: “Democracy is not just freedom to criticize the government or head of state, or to hold parliamentary elections.”

Real democracy, she said, is “the ability to change the system of industrial capitalism … a system based on class division, patriarchy, and military might, a hierarchical system that subjugates people merely because they are born poor, or female, or dark-skinned.”

El-Sadaawi’s positions haven’t changed much since writing that nearly 30 years ago, and neither has she. Sitting primly in her small, modest apartment in the poor Cairo neighborhood of Shobra, El-Sadaawi told GlobalPost, “I don’t go with the crowd. I am a radical woman.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?