Government crackdown on labor groups worsens in South China

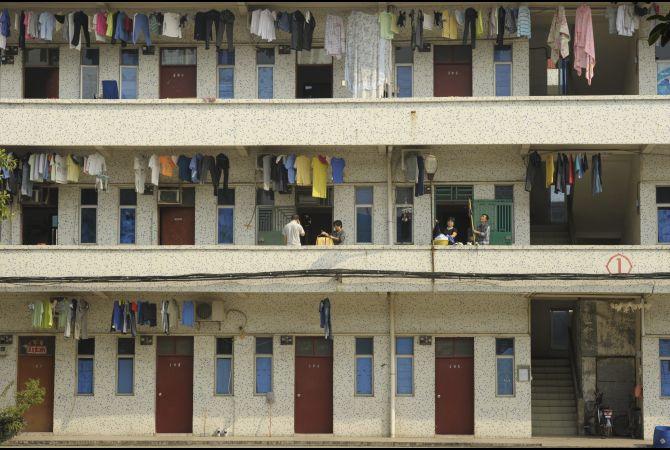

A view of Chinese migrant workers' accommodations in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen. China's migrant workers, who have powered growth with cheap labor, are showing new knowledge of their rights and political sophistication as they seek higher pay and better conditions.

SHENZHEN, China — At least a dozen labor NGOs have suffered forced evictions or have had to close offices in the city of Shenzhen in southern China, after their landlords came under pressure from unknown higher authorities in what the groups say is a series of crackdowns that started late last year.

The latest incident was the violent eviction of workers at the Little Grass Center for Migrant Workers by a group of two dozen hired thugs who smashed windows and broke down the front door of the office — all in front of local police and other bystanders — on the afternoon of August 30, a video posted on the group's blog shows.

In Shenzhen, a booming city of 15 million at the heart of the country’s manufacturing belt, around 12.8 million do not have a hukou, the internal registration system that ties a person and their social benefits such as medical insurance and pensions to a specific location in China.

Most are migrant workers, who say companies see them as disposable labor and are not protected by the official labor organizations and the courts in the city.

“We cannot survive in Shenzhen because there are so many restrictions,” says Song Wenhai, a 44-year-old migrant worker from Hubei Province. “We want to participate but there are so many barriers.”

The crackdown on labor NGOs comes at a time when the Guangdong provincial government was starting to implement what appeared to be liberal labor policies. These have included stricter enforcement of labor law, raising the minimum wage, encouraging direct representation for factory workers and allowing NGOs to register independently without having an institutional sponsor.

“We were very excited at first and thought there would be more room to develop NGOs,” says 32-year-old Chen Mao, a representative from the Shenzhen Migrant Workers Center, one of the groups that has been evicted. “But the pressure on the NGOs has raised a lot of questions about whether this is a real opening or just a new series of social management policies — we’re very confused about what’s going on.”

Continued Harassment

Since the eviction at Little Grass, its members and their families have been repeatedly questioned by plainclothes police officers. At least one migrant worker who helped the group look for a new office was locked out of his apartment and told by police to move out of Shenzhen, the group said.

Just a day before the eviction, a worker from Little Grass who met to discuss recent pressure on the group but did not want her name used said she had feared such a violent end for the group.

“We feel very vulnerable now,” she said. “They can use all kinds of legal reasons or could hire thugs to come after us if they really wanted to close us down.”

Over the last two months, the landlord for the building the organization’s office is housed in had become increasingly insistent that they move.

“I could tell that she was terrified,” the young woman said. “She used to be very supportive, but all the sudden started accusing us of anti-government activity, saying we were [government-suppressed spiritual group] Falun Gong, and things like that.”

In the weeks leading up to the eviction, authorities from several agencies threatened Little Grass with 50,000 yuan ($7,875) in fire safety violations, but implied that if they removed the placard with their name from the office and posted a note saying the organization was closed, the fine would be forgotten.

Three of Little Grass’ six employees have also been evicted from their apartments in recent weeks. “My landlady told me that the next time I rent an apartment I should not use my real name because I’ve been put on a blacklist,” the worker said.

Zhang Zhiru, a 38-year-old Hunan native that heads the Spring Breeze center for migrant workers, says his group has been forced to close two of its three offices in the past several months, one of which was also threatened with fines for alleged fire safety violations.

Shenzhen: No Place Like Home

Since he began working in Shenzhen furniture factories in 2004, Song has lost the tip of his right pointer finger above the knuckle to a saw accident and broken a hip by falling from stacks of planks piled higher than legal safety standards allow. The fall put him out of work for a year. In both cases, he says he was not properly compensated for the accidents.

For the finger he received $475, and still nothing for his hip. The company offered him the lowest pay grade of 900 yuan a month, about $141, over the year he was out of work.

Song and his friend Wu Baozhi, a 40-year-old worker originally from Henan Province, have both sought help from the Shenzhen Migrant Workers Center. Wu said his hard luck comes from a series of layoffs over the past year — four in all —from factories that employed him, then dumped him just before his probationary period was about to end, examples of so-called “strategic layoffs.”

Both men say they have tried appealing to the courts, government institutions and the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) — the only legally sanctioned trade union in China — to seek redress, but to no avail.

“We’ve gone to the trade union, but they don’t help us,” Song said. “The trade union is like a vase, just a decoration on a table.”

New Tricks of the Trade

The use of labor dispatch agencies to hire workers for what are supposed to be temporary positions has boomed due to loopholes in the 2009 Labor Contract Law went into effect, many China labor watchers say.

Official estimates from ACFTU say around 60 million such workers were being used in China in 2010.

Zhang of Spring Breeze said the number is likely closer to 70 million now, which would mean labor dispatch workers make up around 10 percent of the total labor force in China. Companies have been able to get around many aspects of the Labor Contract Law by hiring through the dispatch agencies, then keeping workers on longer than six months, not paying them proper overtime, not paying them at salary levels of workers contracted directly by companies for the same positions and many other similar evasions.

“China is creating too many laws but not implementing them,” Zhang says. “Enterprises are taking advantage of the loopholes, there are too many loopholes. I think they should get rid of labor dispatch agencies because it puts people under two bosses.” Revisions were proposed this summer to tighten an article in the law and are likely to pass, but even those within labor dispatch companies themselves don’t think the changes will make much difference.

Zhao Jiawen, president of the Shenzhen Jincao HR Information Advisory Service Company, one of the top three labor dispatch companies in Shenzhen, said the tighter restrictions on companies like his is only forcing them to adapt and will only impact smaller companies. About 10 of his clients have already begun to get ahead of these changes by directly outsourcing parts of their operations — say human resources divisions, clerical work, or even particular lower-end manufacturing positions — directly to the labor dispatch companies.

So instead being dispatched to a business, the workers instead simply work for the dispatch company so they are not technically dispatch workers anymore.

“The revisions are meant to regulate the labor dispatch services, but we have ways to avoid that by changing how we offer our services,” Zhao said.

Take It or Leave It

Outside the Shenzhen Jincao offices, workers mill about, browsing over ads for jobs pinned to large bulletin boards in the hallway.

A 36-year-old construction machinery operator from Jiangxi named Peng, who just arrived in Shenzhen last week, is on his way out the door after securing a recommendation letter to get an interview for 4,000 yuan per-month ($630) bulldozer driving job.

“The pay is not that good, but not too bad,” he says. “Others sometimes get half for the same job.” Li Yaoyuan, a 19-year old from Jiangxi province stands smoking outside the door and reads the four or five posted jobs there, seemingly not wanting to get dragged too far into the offices. “My friends have told me not to take contracts from labor dispatch companies,” he says. “But you can’t go directly to a lot of the factories to get a job, you have to get a recommendation letter from the dispatch company first, and if you get the job you pay 100 yuan ($15) to the agency.”

Zhang of Spring Breeze says labor dispatch companies should be banned, and has led gotten 10,000 signatures calling for as much. Last November he attempted to run for village elections in his local district, but aborted the campaign because of pressure from local authorities and after one of his colleagues was arrested for handing out his platform flyers.

“I was not even allowed to pass out their own official notice about the election,” Zhang said with a wry smile. “I pasted it to a wall and they ripped it down and told me ‘you’re not allowed to publicize the election.’”

In the Dalang County area of Shenzhen where Zhang lives, only 6,900 of the 350,000 residents are hukou holders, he said. Of the 60,000 residents in the area he would have represented, only 797 were officially allowed to vote, and only three of those were non-hukou holders — his wife, his colleague and himself.

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!