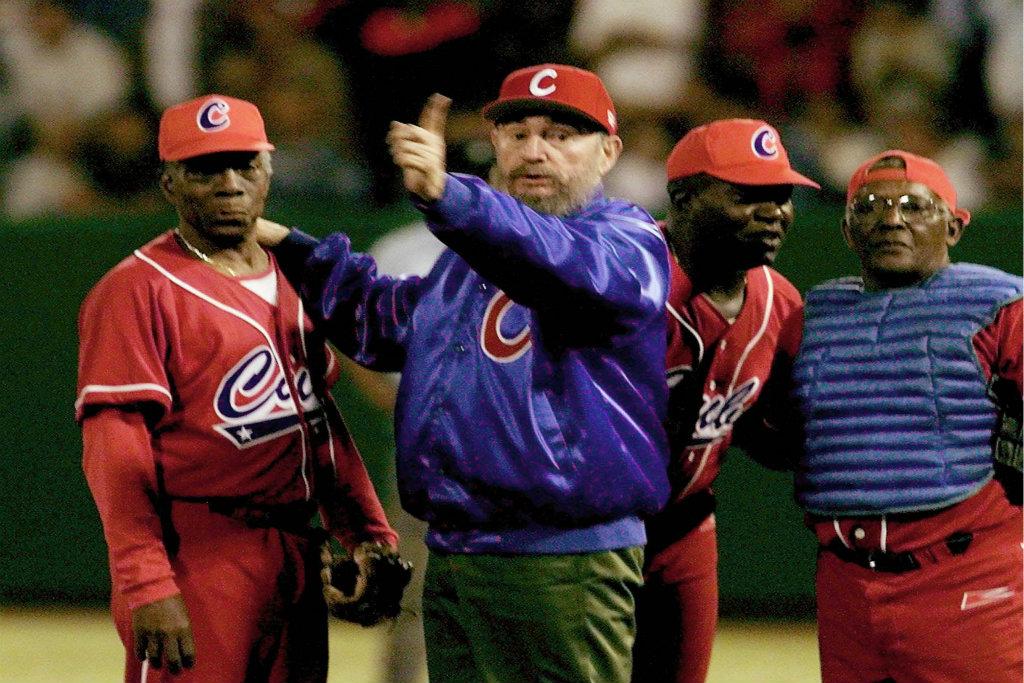

Cuba, out at home

Former Cuban President Fidel Castro (C) makes a call during the game between Venezuela and Cuba.

HAVANA, Cuba — In the current season of record-breaking contracts for Cuban baseball talent, it's tempting to wonder what might have happened had Antonio Castro gotten his way.

Rumors began circulating in late 2010 that Castro, one of the highest-ranking baseball officials in Cuba and a son of Fidel Castro, had advanced a proposal to allow the island's “peloteros” to play professionally abroad.

The players would still represent Cuba in international competitions. But they could spend part of the year and a portion of their careers earning large sums in professional leagues abroad, with taxes on their salaries helping to generate much-needed revenue for Cuba's baseball leagues back home.

Excitement about such an arrangement spread as highly regarded Cuban ex-players and personalities seemed to endorse the idea in public, their once-taboo comments appearing in Cuba's state media.

Victor Mesa, the manager of Cuba's national team, was quoted in 2010 questioning the prohibitions on Cubans playing abroad.

After all, the top stars from ideological ally Venezuela play in the United States and elsewhere during the summer. Then they return home to play in the country's own winter-league season, just as Cuban stars often did before Castro's 1959 Revolution and the unyielding turn against professional sports that followed.

“If other countries can do it, why can't we?,” Mesa asked. “In the end they'll just steal the players anyway.”

Rey Anglada, another former star and Cuban baseball manager, told Cuba's Prensa Latina: “Times change.”

“There are Cuban players who have wanted to test their luck,” Anglada said. “They see themselves having possibilities and see others who have done well. I don't see how that can stop.”

The Castro plan that supposedly circulated in 2010 would have been nothing less than a Cuban baseball revolution. But it seemed like an eminently sensible way to stem the constant stream of defections that have become a major drain on the island's athletic talent, not to mention the players and their families.

Only the proposal seemed to land in a drawer, and there's been little talk of it since.

More from GlobalPost: Cuba mute in the time of cholera

Meanwhile, the financial pull of big league payola has soared to new heights for Cuba's highly coveted “amateurs.”

Cuban defectors this year have signed more than $100 million in free agent contracts — shattering the old records for Cuban deals and sending dreams of riches through every level of Cuban baseball.

The first stunner was the four-year, $36 million deal signed by outfielder Yoenis Cespedes with the Oakland A's in March, a record amount for a Cuban defector at the time. Cespedes allegedly fled from the island to the Dominican Republic on a speedboat sent by baseball agents, taking his entire family along to avoid the painful separation that often punishes Cuban defectors who leave illegally.

Cespedes went straight into the A's starting lineup, batting cleanup, and was named American League player of the week on Monday. He's batting over .300 so far this year.

Three months after Cespedes' signing, the Chicago Cubs reached a nine-year, $30 million deal with 20-year-old prospect Jorge Soler, who had defected to Haiti. It was huge money for a player who had yet to prove himself in the Cuban leagues, let alone in US Major League Baseball.

The records were broken again last month when the Los Angeles Dodgers signed 21-year-old Cuban outfielder Yasiel Puig to a seven-year, $42 million deal, the most ever for a Cuban defector.

Puig, like Soler and Cespedes, had never played a single inning of professional baseball.

But Cuba's participation in international competitions has given professional talent scouts new opportunities to size up the island's players.

Cuba's national team is still loaded with ballplayers who could go straight into Major League lineup — and potentially draw even bigger contracts.

One is Cuban slugger Alfredo Despaigne, who set Cuba's single-season home-run record this year.

Players such as Despaigne are celebrities on the island, whom the government often rewards with cars, a home and other perks. But cash-strapped Cuba can't compete with the millions its stars could make abroad playing “pelota capitalista.”

Would a player like Despaigne choose to maintain ties to Cuba if he were allowed to play professionally abroad, in exchange for sharing a portion of his millions with the Castro government?

That is the question Cuban athletic officials may be wrestling with, since whatever happens in baseball could become a model for other athletes, including that other big-money sport in which amateur Cubans excel, boxing.

More from GlobalPost: MLB defends Dominican recruitment after documentary

US trade sanctions against Cuba would make it impossible for the island's baseball stars to play in the Major Leagues, so they would have to continue to defect and break ties with the island. But the players could sign with teams in Japan, Mexico, Venezuela and anywhere else in the world.

A handful of Cuban baseball legends have been allowed to play professionally in the Japanese leagues at the end of their careers. The experiment hasn't been expanded, and it's not clear why.

Instead, forced to choose between a poorly paid amateur career at home and a shot at a life-altering payday abroad, Cuban players continue to resort to defections. They know it's the best chance they have to take care of their family’s financial needs for life, and test their skills against top competition.

Communist party officials view the defections as “betrayals,” but ordinary fans on the island grew accustomed to them long ago. They quietly follow the success of Cuban big-league stars like Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez and LA Angels slugger Kendry Morales via word of mouth or the internet, even though the players' names are never again mentioned in Cuba's state-run sports broadcasts.

Cuba's national team is currently playing in the Haarlem Baseball tournament in the Netherlands, and will face more international competition — and the temptations of talent scouts — when the preliminary rounds of the World Baseball Classic begin in November.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?