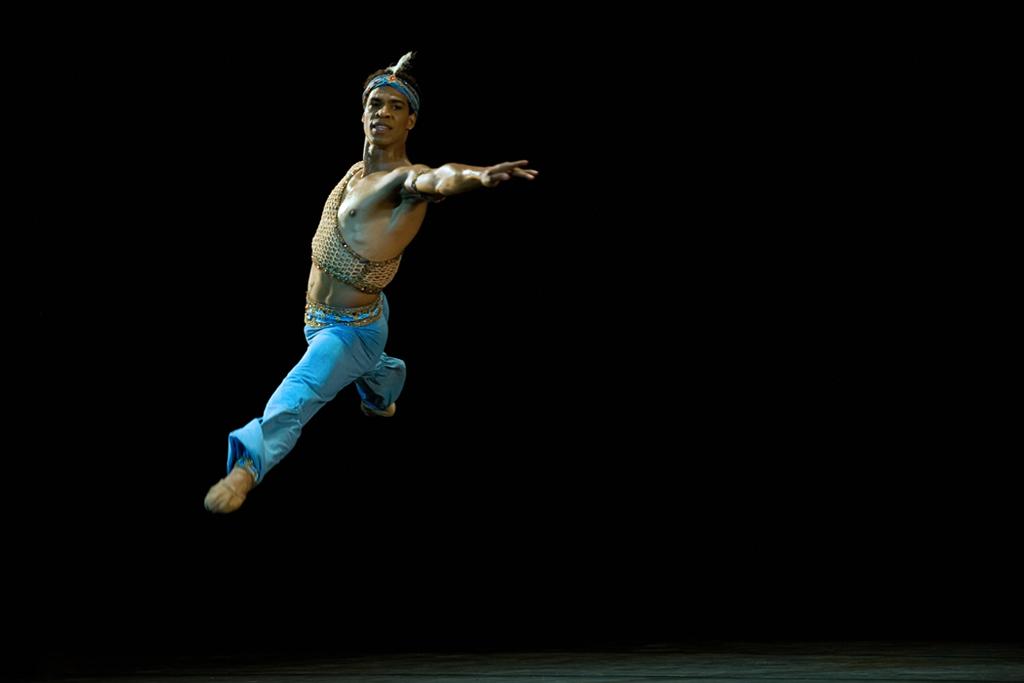

Carlos Acosta’s Cuban renovation

Carlos Acosta, a Cuban dancer with the UK’s Royal Ballet, performs on July 15, 2009 at Garcia Lorca theater in Havana during a special presentation with members of the Cuban National Ballet.

HAVANA, Cuba — For a society so steeped in the idea of “revolution,” Cuba can be a place of uncanny sameness. The same leaders, the same food rations, and the same old cars endure year after year.

But once in a while, a powerful new idea comes along that jolts the stasis and forces a moment of reckoning.

That is the type of a proposal that has been put forward in recent months by global ballet star Carlos Acosta, a figure as famous on the island as any baseball player or Olympic athlete. With Acosta preparing to retire from London’s Royal Ballet, he has announced plans to return to his homeland and convert a ruined ballet school into a state-of-the-art dance academy and global cultural center.

With millions in privately raised funds from the capitalist world, Acosta is offering to save one of the island’s most important architectural landmarks, the long-forsaken National Ballet School on the grounds of the former Havana Country Club.

If that sounds like a mere matter of tutus and leotards, it is not.

More from Cuba: Entrepreneurial vibes are stirring in Havana (audio slideshow)

The project was started in 1961, only to be abandoned four years later and left to sink into decades of bitterness and decay. Nearly a half century later, the Carlos Acosta International Dance Foundation will step in where Cuba’s socialist system has stumbled.

“Isn’t it a beautiful idea?” Acosta wrote in an open letter published on the island this summer, explaining the genesis of his plan. “Even more beautiful is that it wouldn’t cost Cuba a cent, and the entire arts center could provide the money that the Ministry of Culture needs to rescue other facilities in bad shape.”

The Cuban government has agreed, backing Acosta so far on the broad outlines of the plan.

Acosta’s project has far-reaching implications in a country where the arts and arts education have been dominated by the state for more than 50 years, nurturing generations of top ballet and modern dance talent. The project carries the possibility of an entirely new relationship between Cuba and its most successful artists and athletes, many of whom have left the island to seek personal fortune and professional fulfillment abroad.

Once viewed as traitors or sellouts, such Cubans could return as philanthropists, helping restore the island’s other crumbling schools, stadiums, and theaters with private funding. If Acosta can run an arts center with relative autonomy, then perhaps a Cuban baseball defector could return to run a sports academy, or a Cuban boxer could fix up a training gym.

More from Cuba: Closure of popular Havana cabaret tests Castro's reforms

Cuba’s top cultural officials are praising Acosta’s plan, aware that they have an opportunity to transform the way Cubans abroad engage with their homeland. In an interview, Miguel Barnet, head of Cuba’s Artists and Writers Union, said he viewed Acosta’s offer as “a new way to open doors to the future.”

“We have to wipe off the bureaucratic mentality that things that come from abroad are bad, or poison,” Barnet said.

Barnet said Acosta is one of many “artists that are famous [who] don’t live here any longer, but love their country” and “can help contribute to the development of our cultural life.”

The buzz surrounding Acosta’s proposal has only intensified with the announcement that famous British architect Norman Foster has lent his name to the fundraising efforts and produced a design for the renovation of the school.

With a star international architect, a well-connected dance icon, and a landmark building, it would seem like a project with a high chance for success. But though Cuba’s abandoned Ballet School was built on good intentions, it has long been a monument to their failure.

***

In late March 1961, just weeks before the Bay of Pigs invasion would try to topple Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolution, the 34-year-old Castro invited a friend and former Argentine golf caddy named Ernesto “Che” Guevara to show him how to play the game.

Castro wasn’t really interested in putting technique. The outing was meant to poke fun at the new golf-loving American president who was Castro’s emerging rival, John F. Kennedy. The next day, the two bearded, guerrilla duffers made the front page of The New York Times, sporting military fatigues and combat boots on the greens at Havana’s Colinas de Villareal golf course.

“Castro Tries Sport of ‘Idle Rich,’ Says he Could Beat Kennedy,” read the Times headline.

A few days later Castro spotted a young Cuban architect he knew on the street, Selma Diaz, and took her aside. The game with Che had given him an idea for another golf course he’d recently nationalized, the Havana Country Club, at the heart of the city’s wealthiest enclave.

There, on the lush, rolling grounds once frequented by Arnold Palmer and other PGA stars, Castro told Diaz he wanted her to build “the best art school in the world.”

That night, Diaz went to the home of a young Cuban colleague, Richard Porro, and asked him to design the campus. He accepted without hesitation.

“I told him there was one more condition: he had three or four months to produce the design,” Diaz recalled. “Only no one here had ever built an art school before."

Porro recruited two Italian colleagues he’d met while working in Venezuela to help him. They went to work immediately, laboring feverishly in the basement of the clubhouse at the golf course. Castro gave them an unlimited budget and total artistic freedom.

More from Cuba: Where getting rich is inglorious

Putting greens and sand traps were soon bulldozed to make way for Cuba’s National Art School. The design was unlike anything ever built in Cuba, or anywhere else in Latin America. The plan called for five distinct but aesthetically related schools (Visual Arts, Theater, Music, Modern Dance and Ballet), where the sons and daughters of sugar cane workers and chambermaids could master elite culture without paying a dime.

With the US embargo in place and Cuba’s economy already floundering, certain building materials were unavailable from the start. So the architects chose locally sourced materials, like brick and red terra-cotta tile. They lacked cement and metal rebar to reinforce the buildings, but they found an old European mason who knew how to build dome-like “Catalan vaults,” making the arching structures one of the central motifs to the project.

“It was a time when anything seemed possible,” said Roberto Gottardi, one of the two Italian architects, now 85 and still living in Havana. He had arrived in Cuba only four months earlier, barely spoke Spanish and had never directed his own project before.

“Everyone was so young, and had been given such responsibility,” he said. “There was so much enthusiasm and trust.”

While construction crews worked, students moved into the abandoned mansions of the Country Club members who had fled the island in the early days of revolution.

But the days of idealism and romance were doomed. As the Cold War confrontation with the United States escalated, the wide-open promise of Castro’s Revolution was giving way to fear, conformity, and militarism as Cuba drew closer to the Soviet Union.

Long before they could be finished, the art schools came to be seen as wasteful and frivolous, too wrapped up in aesthetics at a time when precious resources were scarce. Blocky, drab Soviet architecture was the new standard, with its pre-fabricated materials and “scientific” pretensions that emphasized function over form.

By 1965, construction on the art schools had been completely frozen, with only two of the five structures complete. Porro, the Cuban architect, left the country soon after. Vittorio Garatti, the other Italian architect, was jailed in the 1970s and expelled from the country.

His Ballet School was left 90 percent complete, then orphaned. Alicia Alonso, the head of Cuba’s National Ballet, never liked the design, however spectacular. She found Garatti’s circular dance studios and performance spaces impractical, saying they were disorienting for ballet students who need four walls to keep their bearings.

The Ballet School was converted to a circus academy for a time, then abandoned to the elements. Looters moved in, followed by the creeping tropical vegetation. The buildings — now considered the most spectacular example of post-Revolutionary architecture in all of Cuba — were left to waste away before they were ever finished.

Today, birds, bats, and neighborhood boys come and go through the ruins of the school as they please. The ground floor is streaked with mud, flooded periodically by the nearby Quibu River. But the buildings are still intact, and reported to be structurally sound. They rise out of the lush green jungle in a swirl of red brick and tile, like some Florentine cityscape gone mad.

***

The art schools and their designers enjoyed a bit of renaissance in the late 1990s, after foreign scholars took interest in the structures and the US historian John Loomis published his book “Revolution of Forms: Cuba’s Forgotten Art Schools.”

An apologetic Fidel Castro presided over a meeting that brought together the school’s architects in 1999, with the aging “comandante” promising to finish the job. It never happened. The two schools that were already complete — Visual Arts and Modern Dance — were renovated, and additional work was performed on the half-finished Theater School.

But the Cuban government ran out of money again, and the schools were abandoned a second time.

Another decade later, Acosta has stepped forward: a figure who is the living embodiment of the dream Castro devised that day while golfing with Che.

Born into a poor Afro-Cuban family with 10 siblings, Acosta studied ballet at a state-sponsored dance academy. He went on to Cuba’s National Ballet, then left the island in the early 1990s to global stardom. But he kept close relations with Cuba, and never waded into anti-Castro exile politics.

Whatever Acosta’s merits as a visionary though, he has tripped up so far in his attempts at managing public relations for the Ballet School project.

When Foster released initial plans for the renovation, generating a buzz in the international press, several prominent Cuban architects reacted angrily, raising questions about the ethical implications of changing Garatti’s original design without his consent.

After all, the buildings are a national landmark in Cuba, and currently under consideration to become a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“It’s a question of creative rights,” said Selma Diaz, the architect who Castro first approached that day in 1961. “Garatti isn’t dead. If he were dead, or incapable of working on the design, that would be another matter. But that’s not the case. He’s lucid, and his rights need to be respected.”

More from GlobalPost: A snapshot of Cuba's economy and reforms (infographic)

Since the Ballet School is a national monument, the country’s Landmarks Commission will have to approve any alternation to the design. Having seen Garatti suffer once when his schools were left unfinished, then a second time when he was expelled unjustly from Cuba in the 1970s, there is a sense that his colleagues from the 1960s don’t want to see his project succumb to a final injustice.

Garatti himself has sent a personal letter to Fidel and Raul Castro, raising concerns that Acosta’s plan will “privatize” the school, but Barnet said the fear is completely unfounded.

“For heaven’s sake, it’s never going to be privatized,” Barnet said. “It’s declared as national heritage, so it’ll never be private.”

Acosta has since returned to London, but his open letter published in Cuba contains a thinly veiled threat that he’d be willing to take his dream somewhere else if his ambitions are blocked in Cuba.

“My greatest wish is to do this project in Cuba, but I would be perfectly fine doing it in another country, for example, in England,” Acosta wrote.

According to sources with knowledge of his plans, Acosta has already raised at least $3 million for the renovation effort.

It will now be up to Cuban cultural officials to bring Acosta, Foster, and Garatti together around a plan that modernizes the school while respecting its original design. But if they cannot reach an agreement, there are some in Cuba who would rather see Acosta and Foster build something entirely new — and leave Garatti’s school as a historical monument, fading away gradually.

“It would be the more respectful, if sad, way for it to end,” said Mario Coyula, one of Cuba’s most respected architects. “It could be used as a ruin, and then this building would have the privilege of reflecting the atmosphere of Cuba in the early 1960s,” he said.

“It would be the perfect symbol of the passing of time, and it would be a decent death,” said Coyula. “Because a building, like a person, has to die,” he said. “So let it die decently.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!