Brazil: Rio shuts makeshift police-run jails

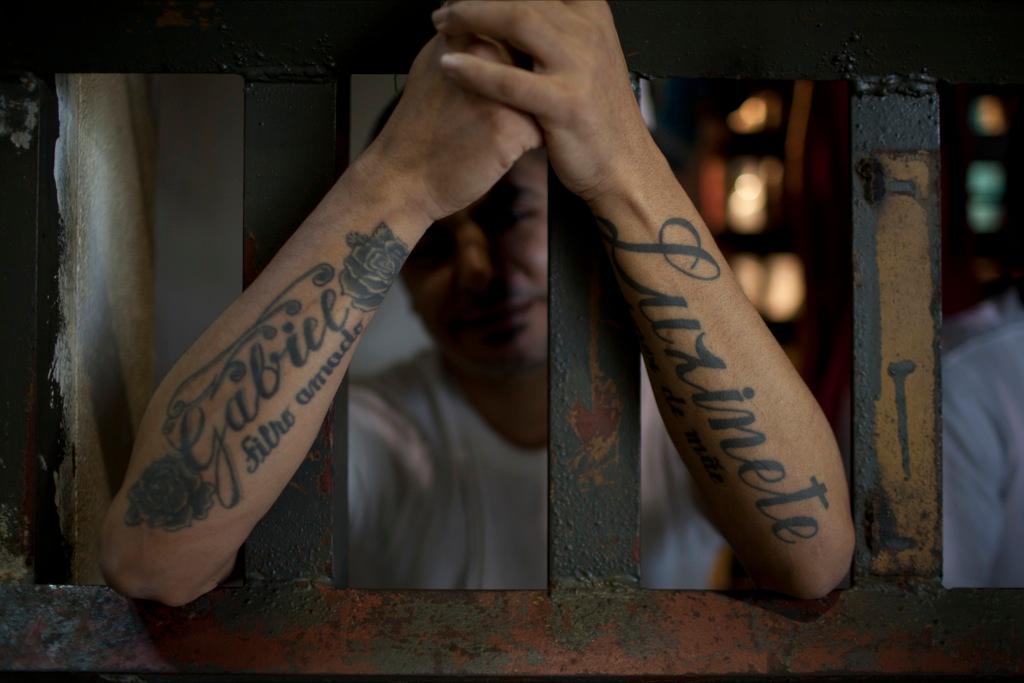

An inmate of an unauthorized holding center is apprehensive about an impending transfer to a new facility. His arms are tattooed with dedications to his son and mother.

SAO GONÇALO, Brazil — On a dank commercial street in this working-class suburb of Rio de Janeiro, women and babies line up with tupperwares of beans and grocery bags with crackers in front of what used to be a horse stable. Hundreds of men accused of drug trafficking, murder, robbery, sexual assault or paramilitary activity are waiting for them inside.

It’s as routine as it is illegal: These ad hoc police-run jails were never meant to exist.

With official prisons overflowing, police across Brazil for decades have turned to whatever structure they could find — in some cases old buses and shipping containers — to house their detainees. But what was meant to be a temporary holding pen became years-long imprisonment for suspects waiting for a trial.

These jails operate with no budget or administration. Detainees’ family members bring them food and other necessities. Some privileged prisoners are chosen to run the jail under the watch of a few policemen. Corruption has flourished.

“We found a case of a boy who had robbed codfish. We found a case of a transvestite who threw a rock at a car because someone had called him ‘fag,’” says Pastor Antônio Carlos Costa, president of the protest group Rio de Paz. The group, one of Rio’s leading human rights organizations, has lobbied hard to get the jails closed and has routinely brought medical supplies to prisoners.

Read more: Packed prisons (INTERACTIVE)

“We found people staying there for three years because they didn’t have lawyers. They didn’t have any information on their judicial processes.”

Human rights groups applauded as Rio de Janeiro became the first Brazilian state to fully shut down these illegal holding pens last month, transferring the last of about 4,000 prisoners out of the police stations.

But where will they go? Some critics are warning that many of the government’s promised custodial houses have yet to be constructed, and the rest of the prisons are bursting with inmates.

The closures are a sight to see. On a recent Saturday, family members here in Sao Gonçalo were startled to see a moving truck pull up to the dilapidated yellow gate of the ad-hoc holding center with a sign reading “Citizens Jail.”

Some prisoners in Bermuda shorts heaved air conditioners, blenders and refrigerators out of the trashed jail into the truck. They are called the “faixina,” a privileged group that enjoys cushier cell rooms in exchange for carrying out cleanup and maintenance duties.

The other sweaty, shirtless inmates from what’s called the “tranca,” the locked cells for the rest of the prisoners, climbed handcuffed into an armored van behind them.

Read more: In-depth series on Latin America's prison problems

Brazil’s incarceration rate — now at 260 per 100,000 residents — has tripled over the past 15 years. That rate ranks in the middle of Latin America, higher than that of Venezuela and Argentina, but lower than that of Chile or El Salvador. But the sheer size of Brazil means its prison population dwarfs that of any other Latin American country. At half a million inmates, its prison population is six times that of Colombia, the next largest in Latin America. It has the fourth largest incarcerated population worldwide.

Nearly half of Brazil’s inmates are awaiting trial, according to research by a number of organizations including Human Rights Watch.

In 1999, a Rio de Janeiro governor decreed that pre-trial detainees should be kept in spacious custodial houses. But Rio has not built them fast enough to hold the inmates.

The horse stable turned jail in Sao Gonçalo had a maximum capacity of 400 but routinely had 800. Some prisoners say they slept standing up tied to the walls.

But the quality of the treatment of inmates varied greatly.

“For being a jail, the conditions here are great,” says a 46-year-old former car salesman accused of homicide who asked not to use his name. The father of four, who has been held in a police jail for nearly a year, has his own cushion on the floor of a room kept cool by fans. He plays video games and watches TV in the room, located below private conjugal visit areas.

He’s one of the select prisoners chosen for the faixina, which police say are prisoners who have earned their trust. He says he’d rather stay in this unit than go to a regulated prison. “For me it’s going to be really terrible.”

“Of course, because those are the faixina!” shouts another inmate, Antonio de Ednilson da Silva, 22, when asked why some prisoners say they want to stay. In the tranca, he claims 50 prisoners slept in a cell for 10 back to back. “They live in a room with air conditioning. We live in a sauna.” Journalists had recorded the tranca’s airless cells reaching 132 degrees in the Brazilian summer.

But both tranca and faixina prisoners say they will miss the loose rules for visitors; unlike the penitentiary system, where family members spend months in bureaucracy to take out visitors’ cards, the police here were lax on allowing visitors in and out.

Civil Police Inspector Ricardo Rocha, in charge of deactivating the Sao Gonçalo jail, says he and his colleagues are happy to be relieved of a duty that “stained” the police’s image through allegations of abuse and corruption.

“We know [the prisoners’] future is very hard. We know this doesn’t resocialize anyone. But that’s not our job,” says Rocha. “Our job is to keep them from running away.”

Whether a prisoner preferred to stay in the makeshift police pens or go to the official jails seemed to depend on his relationship with the police.

Last year, nine policemen and their associates were arrested in a crackdown by the state’s organized crime unit usually employed to dismantle police-affiliated militia squads. They were charged with gang formation and extortion inside Rio de Janeiro police jails.

More from GlobalPost: The Argentine economy’s fuzzy math problem

A frequent visitor who tracked Sao Gonçalo jail closely, who asked not to use his name in order to preserve his relationship with prison leadership, estimated that some $500,000 reais ($265,000 USD) in payments from relatives and associates of prisoners flowed into the jail each month.

Experts say the overcrowding comes from a lack of investment and political will to spend on new jails, and a slow justice system. Prisoners with rights to be on parole spend excess time behind bars. The government has tried to address this: From 2008 to 2010, the National Justice Council reviewed tens of thousands of prison records to find prisoners overstaying their sentences needlessly. They freed 21,000 in two years.

Brazil has also tried to reform some draconian laws that have kept more inmates locked up. An article in the country's strict 2006 law barred authorities from giving probation to detainees accused of drug trafficking from waiting for trial. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court struck down that article as unconstitutional.

Last year, Congress passed a law that says suspects cannot be detained while awaiting trial if the maximum penalty for their crime is under four years.

More from GlobalPost: Mexican prisons out of control

But overcrowding is still worsening in Rio, precisely because of the closure of police jails.

“The government shut its eyes to the reality which the public knew about all along,” says Orlando Zaccone, a chief of police tasked with overseeing these jails as the movement to close them began. He says some in government thought that having dispersed, smaller jails made rebellions easier to control. “The government chose instead to have small concentration camps.”

Zaccone says the root of the overcrowded prisons is zealous incarceration. “In my experience, 70 to 80 percent of prisoners could be in society,” he adds.

One health worker in a custodial house, who asked not to use her name for fear of losing her job, described how her unit went from its capacity of 700 to 1,300 over the last year.

“Three leave and 60 come in. This happens every week,” says the worker.

Despite the increase of prisoners, she claims her supervisor prohibits raising the limit on turning water on for more than the five half-hour periods allotted for each cell of 130 people. She also says fans were taken out of the cells after supervisors alleged that detainees were hiding goods in them. “It’s becoming a human depository,” she adds.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?