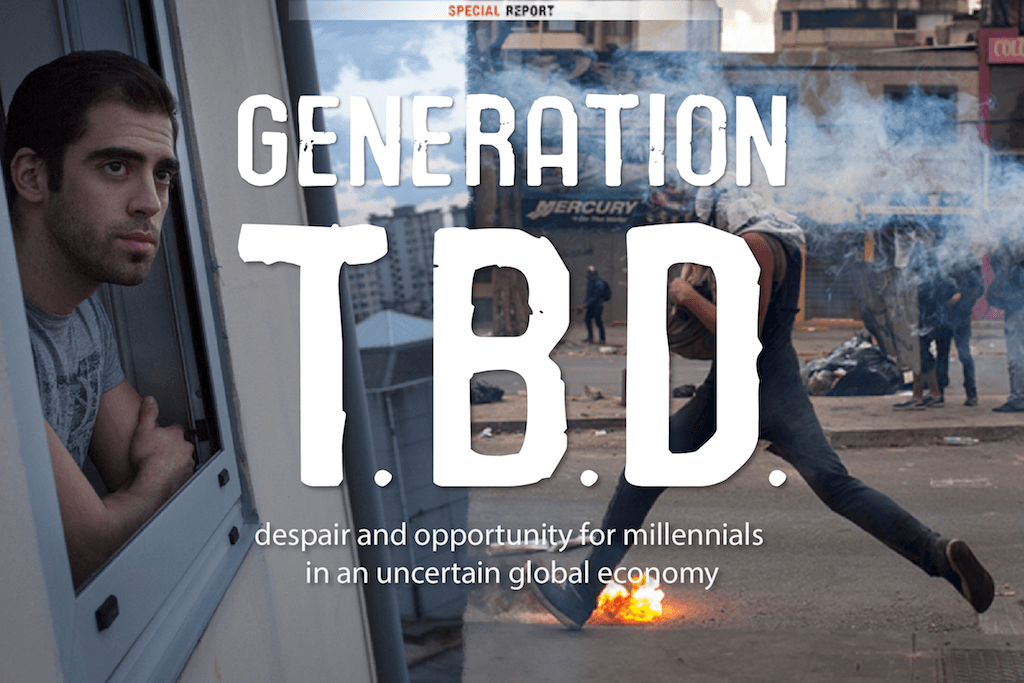

Young and unemployed? You might be part of Generation TBD

ASSIUT, Egypt and LAGOS, Nigeria — It’s been almost four years since Egypt’s uprising seized the world’s attention by ousting former president Hosni Mubarak. It’s been three years since 25-year-old Abdullah graduated college and struggled to find a job.

It’s been two years since he decided to give up on his engineering dream and become a hotel worker.

And more than a year since his father and sister were murdered, victims of the military’s bloody dispersal of an Islamist protest camp in Cairo, along with hundreds of other supporters of Mohamed Morsi, the ousted president.

Abdullah says his days now blur together, but there was once a time when he had hope for something better. A time when it felt like anything was possible, and everyone in the streets knew what they stood for.

“The revolution shook us all, made us think life would be different and better, but it fooled us,” he said as he finished his 10-hour shift at a rundown hotel in Assiut, one of the poorest areas of Egypt, 215 miles south of Cairo. “We’re still poor, even more poor, and there are no opportunities. I couldn’t even travel to Cairo to see the dead body of my father because I couldn’t miss work.”

It’s the new normal in Egypt, not much different than the old, with young people like Abdullah slowly emerging from the hangover of a revolution to find themselves still held down by the same oppressive gravity. And the would-be beneficiaries of Egypt’s uprising – who join millions of millennials worldwide still searching for a future, a group we call “Generation TBD” – remain its neglected victims.

No matter which country I report from across the Middle East and Africa, unemployment almost always tops the conversation, often trumping all other grievances that dominate headlines. Whether in Lebanon or Jordan, Nigeria or Malawi, youth cling passionately to a simple dream of finding meaningful work.

In the impoverished Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, where an unemployed and frustrated 26-year-old Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire almost four years ago and sparked a revolution, sleepy cafes are still filled with scores of young men, all dressed up in pleather jackets with nowhere to go. All Bouazizi wanted was a job. Instead his action sparked a series of uprisings that devoured many of the youth who joined them.

“We didn’t even care about politics,” Abdullah says, sharing stories with his colleagues about the initial days of the uprising in Egypt. All seem startled by how cold they feel recalling a warm memory. “We just wanted more options. Now, it’s all over.”

Nearby in northern Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, Generation TBD’s troubles are exacerbated by the Syrian refugee crisis – the most brutal humanitarian disaster in modern history. I’ve met countless youth in refugee camps and city centers, yearning to make something of themselves, to build among the ashes of their past.

“If I was able to get a degree and then a proper engineering job, things would at least be manageable,” says Hani, a 21-year-old Syrian refugee living in an informal refugee tent settlement in Lebanon. Back in Syria, he was a star student. He had plans to study engineering at a top Syrian university on a full scholarship.

“Without education, without a job… our lives are stalled like a car.”

The dull buzz of that engine echoes more than 2,000 miles away in Nigeria – the most populous country in Africa and the continent’s largest economy. Earlier this year, as part of a reporting fellowship on youth unemployment hosted by The GroundTruth Project, colleague Chika Oduah and I focused on the country’s similarly disenfranchised youth.

At a time when the militant Islamist group Boko Haram rocked the world by kidnapping almost 300 girls, igniting the impassioned celebrity-endorsed “Bring Back Our Girls” campaign, we travelled the country focusing on an even larger enemy that Nigeria’s government has failed to confront: devastating levels of unemployment, paired with a widespread sense of despair and frustration.

Most Nigerians we spoke with said this acute lack of opportunities, amid a culture of government corruption and growing economic disparity, looms larger in their day-to-day lives than the perils of the Boko Haram insurgency.

For many, Nigeria’s staggering unemployment rate and inescapable cycle of poverty has meant a life of crime and violence. For others like 24-year-old entrepreneur Tayo Olufuwa, necessity is the mother of invention, and entrepreneurs are working to fill in the gaping holes the state has long ignored.

“I just realized I could do something with my life,” Olufuwa said, adjusting his black-rimmed glasses while explaining his business venture that connects young Nigerians with jobs. “I could create solutions.”

Those solutions are at the core of a major international conference on youth unemployment on Oct. 24 and 25, hosted by New York City’s International House. The event will feature some of our work from Nigeria and the larger Generation TBD project with reporting from 21 fellows in 11 countries.

In the coming weeks, GroundTruth will publish more of our work on young Nigerians like Olufuwa who have lost faith in in their government, and have often taken matters into their own hands. Their struggles are part of a larger, unhashtaggable fight for dignity – one waged across the world by Generation TBD.

Whether in Upper Egypt, Tunisia, Brazil or northern Nigeria, youth are struggling to dictate their own narratives. And we ought to listen to their rough drafts and half-starts, for Abdullah, Hani and Tayo’s plotlines are more telling than any breaking news event or statistic. Their narratives are also our own and when jaggedly pieced together, they are maps to the future of a generation.

—

This post is part of a special report on global youth unemployment, Generation TBD, produced by The GroundTruth Project ahead of the Generation Jobless conference hosted at the International House in New York City on Oct. 24-25. The event is a solutions-based conference, offering viable, real-world remedies for a critical issue. For more information on the conference, read here. And to follow the conversation on Twitter, look for the hashtags #genjobless and #gentbd.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!