Why China doesn’t mind being left out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership

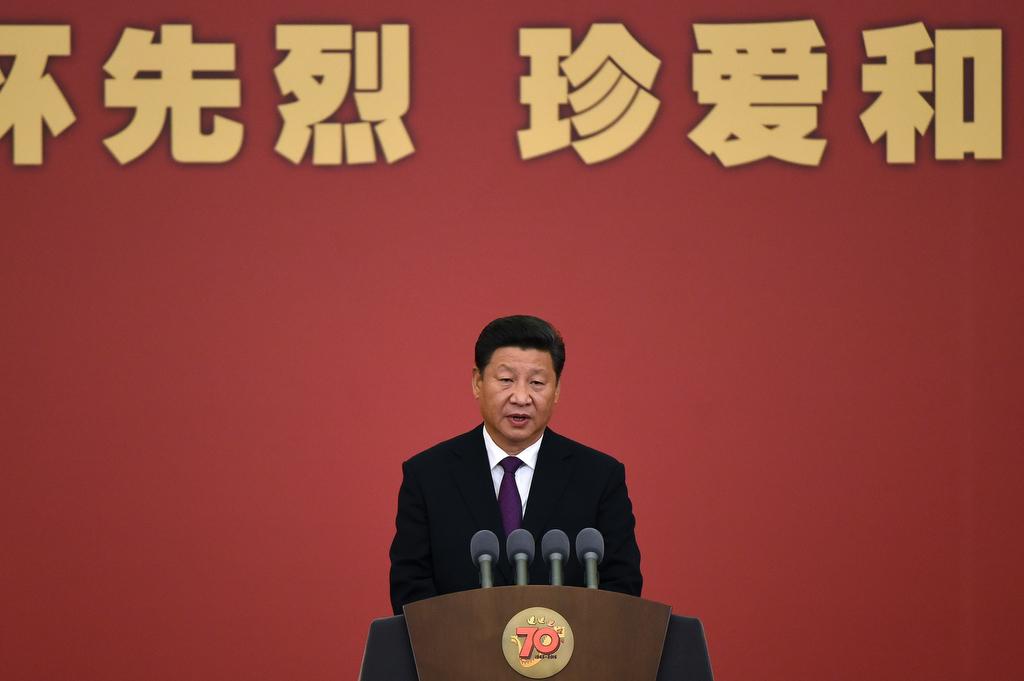

Chinese President Xi Jinping gives a speech at a ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Sept. 2, 2015.

In case you hadn’t heard, the Trans-Pacific Partnership is a really big deal — unless you're China.

The largest regional trade agreement in history involves the United States and 11 countries in the Asia Pacific and the Americas, which collectively represent about 40 percent of world GDP and around a quarter of global exports.

More than five years in the making, the TPP, as it is commonly referred to, was finalized on Monday, but it still needs the approval of lawmakers in member countries, including the US Congress.

Given the importance of the accord, which is designed to boost cross-border trade and investment among member countries and, ultimately, economic growth, it might seem strange that China, the world’s second largest economy and biggest trading nation on the planet, has been left out.

While a lot of the details of the deal are still secret, the TPP is clearly more than just a free trade agreement. In addition to slashing or eliminating98 percentof tariffs on thousands of goods including dairy, beef, sugar, cars, tractors and chemicals, it also establishes common rules and regulations for trade and investment across member countries as well as external tribunals to sort out disputes.

TPP member states will include the United States, Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, Brunei, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Chile and Peru. More countries are expected to join the exclusive trading club, but given the tough membership rules, China is not expected to sign up any time soon.

Perhaps never.

Excluding China has been widely interpreted as an attempt by the United States to curtail Beijing’s growing political and economic might in the Asia Pacific region, and some experts have described it as a “terrible mistake.”

But does Beijing really care? Possibly not as much as you might think.

For starters, China doesn’t need to belong to the TPP to enjoy some of the perks that come with being a member.

Beijing already has free trade agreements with more than half of the TPP countries, including Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Peru, Singapore, Brunei and Vietnam, and it can exploit those arrangements to minimize or avoid import duties that would normally apply to made-in-China products.

Felipe Caro and Christopher Tang of UCLA's Anderson School of Management explained in Fortune magazine this week how that could work.

“To satisfy certain country-of-origin conditions stipulated in TPP, China can manage the supply chain operations of cotton shirts by importing cotton from Pakistan (via its existing free trade agreement with China) and conduct 'upstream' operations, such as fabric design, knitting and dyeing at home.

"Then China can ship the fabric to Vietnam (via an existing free trade agreement with China). At the same time, Japan can ship the buttons to Vietnam (via the TPP). Vietnam can perform 'downstream' operations (sewing) and then ship the finished shirts via TPP agreement to Australia, Japan and the United States, cutting off the 5%, 10.9% and 16.5% import duties that would have applied if China had dealt directly with these countries.”

And China clearly doesn’t require the TPP to enhance its already sizeable influence in the world.

Beijing is a card-carrying member of the World Trade Organization, has a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and is the driving force behind the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which could potentially become a rival to the World Bank and Asia Development Bank once it gets going.

The China-led AIIB, which has the support of dozens of countries, aims to fund infrastructure projects in the region and could help Beijing buy the support of its neighbors.

China is also on track to become one of the world’s biggest overseas investors by 2020, with outbound foreign direct investment already topping $100 billion a year. In some countries, China’s investment is actually bigger than the loans they get from the International Monetary Fund, and that gives Beijing a lot of economic and political clout.

On top of that China is busy negotiating its own free-trade pact with 15 countries in the Asia Pacific region and is expected to become the world's largest economy in the next decade.

“That preponderance is driven by China’s sheer size, its continued growth — which though slower than in the past is still faster than that of most other Asian economies — and its increasing centrality in global supply chains,” Arthur Kroeber, managing director of Gavekal Dragonomics and editor of China Economic Quarterly, told Foreign Policy.

Missing out on a TPP membership card won't change that.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!