Venezuela’s government is sinking in a sea of oil

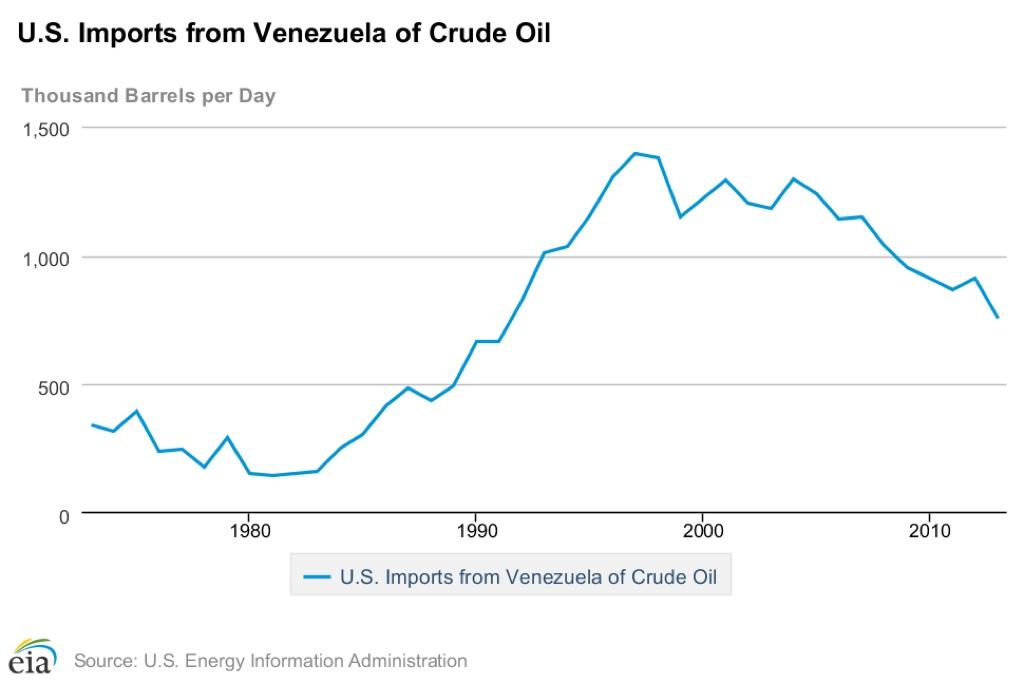

United States’ imports from Venezuela of crude oil are declining.

NEW YORK — Lurking behind the barricades in Venezuela, where pro- and anti-government forces have battled on and off for more than five weeks, one of the biggest contradictions on the planet helps explain what’s gone wrong with Hugo Chavez's Bolivarian revolution.

Over the past decade, discoveries of vast quantities of oil have vaulted the South American nation from seventh to first in the world in terms of proven oil reserves — i.e., oil that can be extracted from the ground. The US Energy Information Administration now reckons Venezuela's reserves hold 298 billion barrels (bb) worth. That's like adding the current estimate of total US reserves (26bb) to that of Saudi Arabia (267bb).

And yet, Venezuela’s oil production and export revenue during the same period have dropped precipitously.

The country that President Nicolas Maduro, Chavez’s successor, inherited has seen oil production sink nearly 25 percent since 2000, most of it due to a lack of investment in new exploration, a massive brain drain and poor maintenance at older fields.

This is particularly apparent in the drop in barrels destined for the United States, whose Gulf Coast refineries are uniquely geared to deal with the heavy, sour crude Venezuela produces.

Venezuelan oil exports to the US peaked in the mid-1990s at over 1.3 million barrels per day (bpd). By 2013 it had fallen below 775,000 bpd.

Oil troubles have helped drain Venezuela's hard currency reserves and exacerbate shortages of basic goods, leading to price gouging and fueling public anger.

The US and Venezuela differ ideologically, and the latter’s leaders regularly accuse the former of compounding their country’s woes. But Venezuela’s economic problems are mostly self-inflicted.

More from GlobalPost: Why the OAS doesn't want you to hear what this Venezuelan has to say

Venezuela uses its oil as a political reward to likeminded governments in the region — hardly a way to close fiscal gaps. And the state takeover of the oil industry has proven a disaster, with production plummeting and investment lagging.

Meanwhile, the US is using less oil overall, and more of what it does use comes from beneath US soil.

Chavez saw some of this coming. Before he died of cancer one year ago, he oversaw efforts to diversify away from the US market and toward China, a somewhat less prickly customer ideologically and one with an insatiable thirst. But that pivot has been excruciatingly slow and clumsily handled. Because of the poor quality of Venezuela's oil, it's not merely a matter of oil tankers plotting a new course. New refineries and ports are needed.

While Venezuela’s oil exports to China have risen (to about 60,000 bpd in 2013) and several large joint projects with Chinese state oil firms are underway in Venezuela, that by no means covers the shortfall of lost American business.

What's more, Venezuela is providing over 200,000 bpd more to Beijing at no charge as a down payment on more than $40 billion in Chinese loans extended during the Chavez years, according to the EIA.

Add another 400,000 bpd transferred at below-market prices to regional Bolivarian brethren — including Cuba, Nicaragua and a host of small Caribbean islands — and it's no wonder the Venezuelan currency, the bolivar, fell 73 percent against the dollar in 2013.

Both Chavez and Maduro have taken steps domestically that make the problem even worse. Besides driving away foreign investment and shedding hard-to-replace energy expertise with expropriations of foreign assets, their governments have heavily subsidized domestic fuel prices, resulting in a jump in the amount of the country's production that’s consumed internally from 36 percent to 47 percent.

Think about it: A government in the tropics floating on the world's largest sea of oil is consuming nearly half of it domestically and squandering much of the revenue that could be derived from exporting the rest.

More from GlobalPost: Maduro says, Obama, give peace a chance, don't kill me

This was not preordained, nor is it all a case of inefficient state monopoly. Norway's Statoil, state-owned for decades, is one of the best-run energy firms in the world.

Nationalized in the 1970s, Venezuela's state-owned oil monopoly, Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), managed a highly successful and lucrative sector through the 1990s. But when state workers went on strike in 2002 over plans to politicize the company further, Chavez fired some 180,000 experienced oil workers, leading to a production collapse.

America's Iraq invasion came to his rescue in 2003, spawning historic high-energy prices that helped plug the Venezuelan state's coffers. Emboldened, Chavez spread subsidies around to quell dissent. Then in 2006, he ordered a state takeover of exploration activities from foreign oil companies, driving out additional expertise, and announced a wave of below-market energy supply deals with likeminded regional leaders that continue to this day. (Cuba, for instance, sends state-trained doctors to Venezuela to do community service in exchange for its steep discount).

The same malaise afflicts its natural gas. Venezuela ranks second in the hemisphere behind the US in natural gas reserves, but the South American country uses it all used to support its rickety PDVSA monopoly.

Because Venezuela's oil fields are older and in decline, they require a process known as enhanced oil recovery whereby natural gas is pumped into the oil wells do drive crude out. All of Venezuela's gas production is used this way — an enormous waste of a critical resource.

Indeed, for the past several years, the country has imported natural gas from Colombia to make up for a shortfall.

With world oil prices moderating, US shale gas and tight oil increasing and Venezuela’s efforts to pivot exports toward China stalled, Venezuela’s oil monopoly is showing scant evidence it can convert the massive new reserves into revenue.

This is seriously denting sales of Venezuelan government bonds — which, besides more loans from China, are the only way for the government to support its deficit spending.

The standoff in the streets of Valencia, San Cristobal and Merida continue, and few analysts see Maduro facing a Ukrainian exit any time soon.

But the death of Chavez saddled his successor without a compass, with a broken patronage machine, a rickety oil industry and an exhausted national treasury.

Venezuela's Bolivarians are literally running short on fuel.

More from the Unraveler: Why the world is worrying about this not-so-precious metal

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?