Right to food wins ‘defensive battle’ in World Trade Organization deal

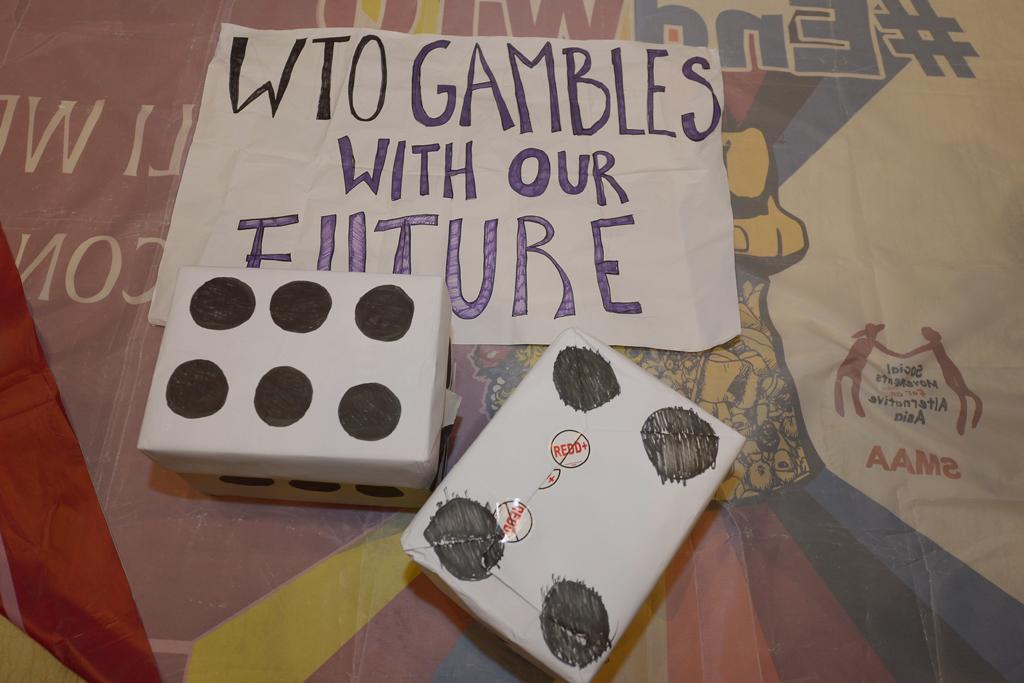

Fake dice are placed by activists from La Via Campesina while they hold a protest against the WTO at the 9th World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Conference in Bali.

BALI, Indonesia — A tense and acrimonious four-day standoff ended Saturday morning at the World Trade Organization meeting in Bali.

A last-minute objection by Cuba and three Latin American allies held up the agreement Friday night, with Cuba objecting to the hypocrisy of a “trade facilitation” agreement – one part of the so-called Bali package – that ignored the United States’ discriminatory treatment of the island nation under the US trade embargo.

Overnight, text was added to reflect Cuba’s concern even if it did nothing to resolve the issue. Call it the story of the WTO.

Leading up to this week’s meeting, the US and other rich countries had attempted to declare India's food security program in violation of the WTO's archaic and biased rules and sought to discipline the program as “trade distorting.”

More from GlobalPost: US opposition to ambitious Indian program a 'direct attack on the right to food'

India and other developing countries fended off the challenge to these programs, which support small farmers and help feed the hungry. But the final agreement is no green light.

Countries considering such programs would not be protected by the “peace clause” that will shield India and some others for the next four years. And onerous reporting requirements put the onus on the developing country to prove that its stock-holding program is not "trade distorting."

In return for the modest protections for food security programs, and a vague package of reforms for the least developed countries, developing countries also agreed here to a trade facilitation package that could benefit some of them but might demand more than they can give.

The package comes with binding commitments for developing countries to streamline customs and other trade systems. Though the timetable for fulfilling these commitments is flexible, developed countries have not promised funding to support such improvements.

A cash-strapped government, then, could end up bound to prioritize improving its port computer systems over public health or education.

In the end, the main beneficiaries of trade facilitation measures are transnational firms that are positioned to export and import and are looking for improved access to developing country markets.

And that is the never-ending story of the WTO in the age of globalization. The Bali Package in no way deviates from that script. But the right to food won an important defensive battle in the larger war for a global trading system worthy of the lofty development ideals of the Doha Round.

The next battle will come within four short years, by which WTO members have committed to resolve this issue for good.

If they resume negotiations, they should begin with the original G33 proposal to remove WTO obstacles to Food Security, as over 300 global civil society organizations demanded in a letter last month. A similar call came from civil society groups from the Least Developed Countries, the Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific Group, and the Africa Group.

They could begin with the simplest solution proposed by India: agreeing to update the antiquated international reference price from the 1980s, which makes any administered price today seem like a massive subsidy.

A barely above-market price of 1,250 rupees per ton for rice looks like a 986 rupee subsidy when compared to the 264 rupee per ton reference price from the 1980s. The actual subsidy was trivial.

The US and other developed countries refused to update the reference point, arguing that they didn’t want to reopen any part of the Agreement on Agriculture. Of course they don’t. They wrote those rules, which favor rich country exporters.

The hope is that all of this attention on subsidies will put the issue front and center in negotiations to come.

“Public stock-holding is just the tip of the subsidies iceberg,” said Martin Khor of the Geneva-based South Centre. “Hopefully we can reveal the rest of the iceberg now and try to fix it.”

Anuradha Talwar of India’s Right to Food Campaign seemed exhausted by the WTO meddling in India’s policy-making.

“The agreement on the table today is going to make it even more difficult to achieve food security for our people,” she said. “And it was hard enough already.”

Timothy A. Wise is the policy research director at Tufts University’s Global Development and Environment Institute (GDAE). He is currently on an Open Society Institute Fellowship on agriculture, climate change, and the right to food.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!