Powerland Shanghai: A green tower for Red China

SHANGHAI, China — The skyline of Pudong in Shanghai has been a symbol of China’s development the last three decades.The city went from a barren mudland at the beginning of the eighties to a wannabe financial center dotted by the highest skyscrapers in the country and, for brief periods, even in the world.In the early 2000s, the city added two supertall towers: the 88-floor Jinmao and the newest Shanghai World Financial Center, with its empty quadrangle in the top that locals started referring to as a bottle-opener.Now, the neighborhood is welcoming a 121-story colossus that is expected to dominate the skies of Shanghai in 2014.Shanghai Tower will speak, as its predecessors did, to China’s successful economic emergence, but it will also be a symbol of the country’s green aspirations.A conglomerate backed by the city’s government asked the architecture firm Gensler to design a sustainable building, one that would set an example for other projects in the country.They complied.The complex will have twice as much floor space as the Empire State Building and will include nine vertical zones for office, retail, restaurants, hotel and other services. It will be a city within the city, with 20,000 occupants who will commute vertically with the help of 106 elevators.For design director Christopher Chan, such grandiosity is not incompatible with being sustainable.“You can take those 20,000 people spread them across the city like peanut butter and you still have congestion, pipes and ducts and stuff and moving trash around,” says Chan. “Or you can put them in a tower in a much more efficient way."The tower’s design and technical features will help reduce overall energy usage by 21 percent, according to Chan. Part of the savings will come from regulating the amount of energy used to light, heat or cool the building, functions that altogether usually account for almost two-thirds of the energy usage in any skyscraper.The desire to conserve energy had a direct impact on the design, influencing not only the look of the building but also how it works. At the top of the building, 632 meters up into the sky, wind speeds can reach 20 feet per seconds. So engineers crowned the roof with more than 200 wind turbines, creating energy that will be used to power the exterior lighting of the complex.It's also the tallest thermos in the world. “It uses two layers as insulation, to keep the heat in during the winter, or to keep the cold in during the summer,” says Howe Keen Foong, one of the building's chief architects.Other elements are also in full use. A funnel-shaped roof collects rainwater and channels it into large tanks in the basement of the building. After it’s filtered and cleaned, the water is delivered to sky-gardens scattered around the atria.Air conditioning for these vertical oases will be constantly recycled according to the designers, and much of it will come from the ice stored in the basement of the building. The ice will be produced every night using off-peak energy and the tower’s own natural gas power plant.“I don’t look at this as a building, this is a very complicated machine," says Howe.

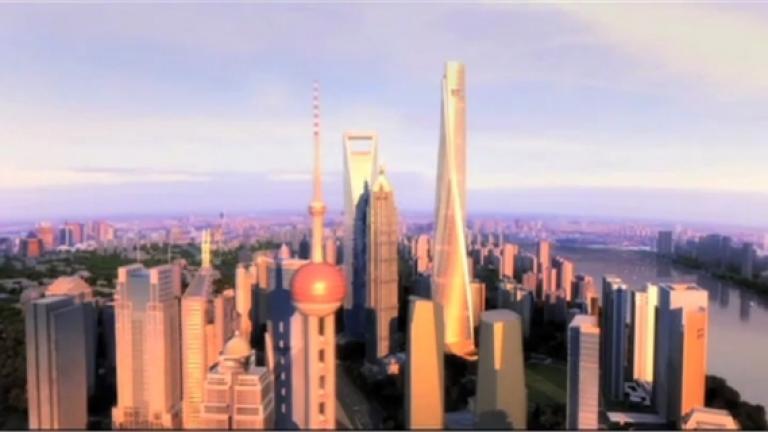

SHANGHAI, China — The skyline of Pudong in Shanghai has been a symbol of China’s development the last three decades.

The city went from a barren mudland at the beginning of the eighties to a wannabe financial center dotted by the highest skyscrapers in the country and, for brief periods, even in the world.

In the early 2000s, the city added two supertall towers: the 88-floor Jinmao and the newest Shanghai World Financial Center, with its empty quadrangle in the top that locals started referring to as a bottle-opener.

Now, the neighborhood is welcoming a 121-story colossus that is expected to dominate the skies of Shanghai in 2014.

Shanghai Tower will speak, as its predecessors did, to China’s successful economic emergence, but it will also be a symbol of the country’s green aspirations.

A conglomerate backed by the city’s government asked the architecture firm Gensler to design a sustainable building, one that would set an example for other projects in the country.

They complied.

The complex will have twice as much floor space as the Empire State Building and will include nine vertical zones for office, retail, restaurants, hotel and other services. It will be a city within the city, with 20,000 occupants who will commute vertically with the help of 106 elevators.

For design director Christopher Chan, such grandiosity is not incompatible with being sustainable.

“You can take those 20,000 people spread them across the city like peanut butter and you still have congestion, pipes and ducts and stuff and moving trash around,” says Chan. “Or you can put them in a tower in a much more efficient way."

The tower’s design and technical features will help reduce overall energy usage by 21 percent, according to Chan. Part of the savings will come from regulating the amount of energy used to light, heat or cool the building, functions that altogether usually account for almost two-thirds of the energy usage in any skyscraper.

The desire to conserve energy had a direct impact on the design, influencing not only the look of the building but also how it works. At the top of the building, 632 meters up into the sky, wind speeds can reach 20 feet per seconds. So engineers crowned the roof with more than 200 wind turbines, creating energy that will be used to power the exterior lighting of the complex.

It's also the tallest thermos in the world. “It uses two layers as insulation, to keep the heat in during the winter, or to keep the cold in during the summer,” says Howe Keen Foong, one of the building's chief architects.

Other elements are also in full use. A funnel-shaped roof collects rainwater and channels it into large tanks in the basement of the building. After it’s filtered and cleaned, the water is delivered to sky-gardens scattered around the atria.

Air conditioning for these vertical oases will be constantly recycled according to the designers, and much of it will come from the ice stored in the basement of the building. The ice will be produced every night using off-peak energy and the tower’s own natural gas power plant.

“I don’t look at this as a building, this is a very complicated machine," says Howe.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!