This man is a pedophile, and proud of it

LONDON, UK — Tom O’Carroll is a pedophile. Every three months, two police officers visit him at home in England, a condition of his 2006 conviction and imprisonment for distributing child pornography. They are always polite, he says.

He keeps a blog. Because he cannot legally have sexual relationships with the people he wants most — children who have not yet reached puberty — he writes to relieve the frustration of unfulfilled desire, and of living in a society that tells him those desires are illegal, harmful, evil, sick.

He believes this conclusion is incorrect. He believes there are children, even those of a very young age, who like and seek sex with adults. He believes that adults who want to satisfy this perceived need should be legally allowed to do so. He believes there are situations where it is all right for adults to have sexual relationships with children.

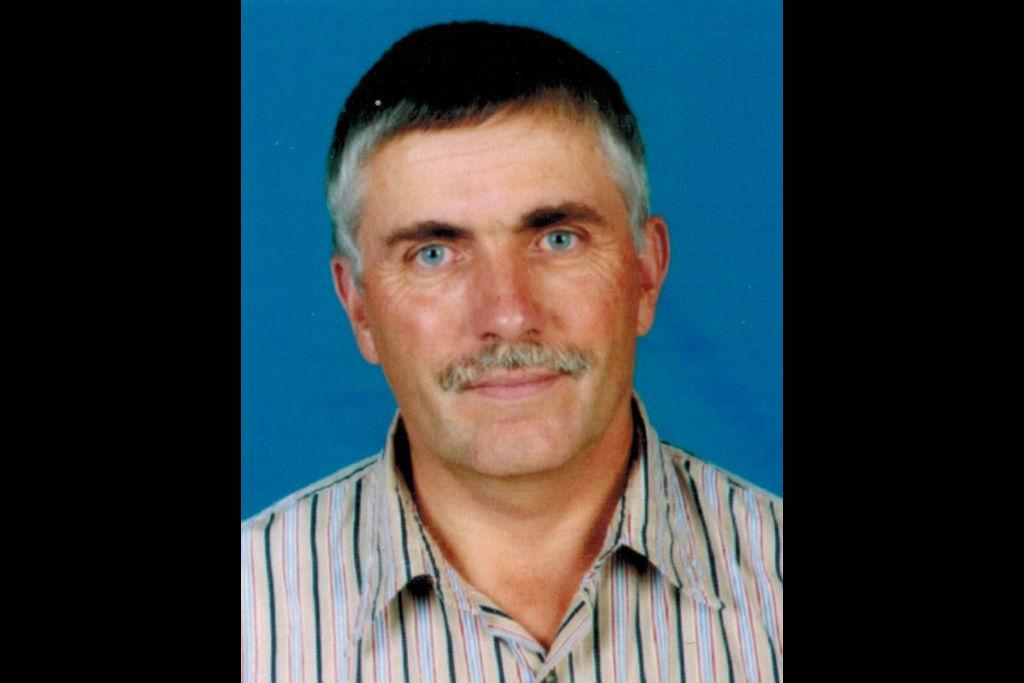

He knows that this makes him a monster in the public eye. He would encounter such revulsion less if he kept these opinions to himself, as most of the few people who share them do. The sex offender registry in the United Kingdom is not public as it is in the United States. No one has to know the most private thoughts of a gray-haired former teacher with ice-blue eyes.

But he can’t stop himself. For almost 40 years, O’Carroll, 69, has been an outspoken advocate of what he sees as his right to desire children, and detractor of those who would oppress those desires.

He has argued this position on television, in books, blog posts and the comment sections of other blogs. He has logged volumes upon volumes of lucid, copiously footnoted prose. When officers failed to take notes during his last monitoring interview in January, he sent them an unsolicited 5,000-word manuscript clarifying and detailing his answers.

The UK is grappling with major investigations of child sexual abuse reportedly perpetrated and covered up by senior figures and institutions in the 1970s and 1980s.

This coincides with a seminal time in O’Carroll’s own history, when his voluminous capacity for argument and extraordinary conviction that pedophilia is “a power for good” found a momentary toehold in the public sphere.

While others sort through shame, anger and unanswered questions, he is among the infinitesimal population of people who looks back at the time and waxes nostalgic for a golden era of pedophilia.

“This was the era of make love not war, and so forth,” he said. “A general liberated atmosphere. Things have gone, as far as I’m concerned, steadily downhill since then in terms of sexual anxiety being greater and greater toward children.”

The pedophile lobby

Before there was the internet, and the alternate universe of pro-pedophilia blogs and forums where O’Carroll and like-minded people now congregate, there was a brief but singular time in British history when their views were allowed their closest ever access to the mainstream.

O’Carroll was a chair of the Pedophile Information Exchange (PIE), a London-headquartered advocacy group that existed from 1974 to 1984 to lobby openly for legal acceptance of pedophilia and to provide an international network for adults with sexual attraction to children.

“Pedophiles do not use a child’s sexuality. Pedophiles develop a mutual sexuality with the child. It’s an entirely reciprocal relationship,” former PIE chairman Steven Adrian Smith told a skeptical BBC interviewer in 1983.

“The responsible and caring pedophile always refers to the firm wishes of the child.”

The group billed itself as another front in the sexual liberation movement of the 1970s.

Even in the age of free love, PIE was considered a controversial fringe element. Staff and students protested O’Carroll’s speaking engagements at universities, and many who spoke up in defense of the group’s right to free speech expressed disgust at its agenda.

But the group was affiliated with the National Council for Civil Liberties, now the respected lobby group Liberty. In a 1976 submission to Parliament on changing the law governing age of consent, the NCCL wrote: “Childhood sexual experiences, willingly engaged in, with an adult result in no identifiable damage.”

In 2013, Liberty Director Shami Chakrabarti said the group’s past connection to PIE was a subject of “continuing disgust and horror.”

PIE’s existence coincided with a time in which widespread sexual abuse of children is alleged to have taken place at institutions across Britain tasked with children’s care.

Multiple police operations, several institutional internal investigations and a national inquiry are now sorting through claims that abusers were allowed access to children in institutions that were meant to protect them, and that government officials knowingly covered up their crimes.

More from GlobalPost: The child sex abuse scandals engulfing Britain

PIE had at least physical proximity to power. During his chairmanship of PIE, Smith actually worked as a contract electrician in the Home Office, which oversees Britain’s police and other security agencies.

Smith kept PIE’s files in a locked cabinet in his office, according to a biographical essay published in 1986 and quoted widely in UK media. His security clearance was annually renewed, he wrote.

PIE Secretary Barry Cutler also worked in the Home Office but was fired in 1983 when a UK tabloid outed his affiliation with the group.

A Home Office spokesman would not confirm or deny either man’s employment.

Other members had high-profile jobs in the public and private sectors, like Peter Righton, a social worker, child protection expert and consultant to the National Children’s Bureau. Righton, who died in 2007, wrote openly in defense of pedophilia even while working in child care homes in the 1970s.

Police are now investigating claims that he was part of an organized ring of child predators that included high-profile figures from Britain’s establishment.

Last year, a retired police officer whose force arrested Righton in 1992 on child pornography-related charges came forward to say that the boxes of papers seized from Righton’s home contained evidence showing “a definite link to establishment figures, including senior members of the clergy.”

The leads he passed to London’s Metropolitan Police appeared to be shelved, Terry Shutt said, and Righton was let off with only a small fine.

“At the time there was a culture to protect the establishment, that it was seen to be more important to protect the establishment than to deal with individuals who may have transgressed,” Shutt told the BBC.

On Monday, an independent watchdog announced a formal inquiry into allegations that the Metropolitan Police deliberately shut down investigations and covered up for powerful abusers.

O’Carroll’s blog reads like a parody of mainstream UK media’s coverage of these events.

When former PIE executive committee member Charles Napier was jailed in December for sexually abusing dozens of boys at the school where he taught in the 1960s and 1970s, O’Carroll eulogized him as “witty, charming, the life and soul of the party,” who “for the most part charmed the pants off his mainly pre-teen pupils.”

Francis Wheen, a prominent British journalist who waived his right to anonymity as one of Napier’s victims, he described as “cry-baby journalist Francis Whine.”

“I’ve been absolutely amazed by the way it’s taken off,” O’Carroll said of the current investigations, in a telephone interview with GlobalPost last month.

“I feel that we now are the bullied ones, not the bullies.”

A ‘moderate’ pedophile

On the phone and in email, O’Carroll is ingratiatingly polite. He describes himself as a “moderate” in the pedophile community, in that he does believe that there should be some laws governing sexual contact between adults and children. Forcing sex on a child is wrong, he says. So are acts that could cause physical damage to a small child.

But he maintains that certain types of sexual touching of children — “things that they would do with each other” — should be okay for adults to initiate.

“Girls won’t even get pregnant,” O’Carroll said. “There’s literally no harm to it.”

He believes that the negative feelings sex abuse survivors report years later — the depression, panic attacks, substance addiction and self-loathing that can haunt people for decades — are brought on by society’s disapproval of the encounter, not the abuse itself.

He has been convicted three times for pedophilia-related offenses.

“I am a great believer in the rule of law,” he said. “I don’t happen to like the rule of law as it applies in certain circumstances, as it applies to me.”

A 1981 arrest for "conspiracy to corrupt public morals" through his PIE work resulted in a two-year prison term. In 2002, he was sentenced to nine months in prison after customs officials at Heathrow airport found naked photographs of children in his luggage on a trip home from Qatar. The sentence was later overturned after the judge was found to have been more influenced by O'Carroll's longtime pro-pedophilia activism than the content of the actual images.

O'Carroll served two and a half years in jail after pleading guilty in 2006 to making, distributing and possessing child pornography.

"Has he ever had sexual relations with minors?" O'Carroll wrote in a third-person online biography. "It is a possibility he has always refused publicly either to confirm (which would of course be dangerous) or deny."

His 1980 book on the subject detailed how an adult might initiate a sexual relationship with a child.

“The man might start by saying what pretty knickers [underpants] the girl was wearing, and he would be far more likely to proceed to the next stage of negotiation if she seemed pleased by the remark than if she coloured up and closed her legs,” he wrote.

“Despite ‘being wrong’ about her intentional sexual seductiveness, he might never-the-less be right in gradually discovering that the child is one who likes to be cuddled and who thinks it great fun to be tickled under her knickers.”

O’Carroll called this a “negotiation” between partners. Sexual abuse experts call it grooming — the process in which a predatory adult builds a child’s trust and confidence so that when abuse begins, their silence and cooperation is assured.

“The very reason we have moral standards and criminal laws to support them in this area is because children are, by their very age and nature, vulnerable,” said Donald Findlater, director of research and development at the Lucy Faithfull Foundation, a UK charity that works with families affected by sexual abuse.

“They are less emotionally and physically developed to make the wisest decisions for themselves or to understand the implications of a proposition brought to them by adults.”

For many people abused by a family member or other adult known to them, this emotional manipulation is one of the most damaging elements of the abuse.

“Who doesn’t like to be made to feel special, to get gifts, to get presents, to feel validated? That’s what grooming is,” said one 54-year-old woman who survived sexual abuse as a child.

An extended family member began sexually abusing the woman when she was 4 until her teens. Having been conditioned to believe that his behavior was normal, and rewarded with gifts and attention in return, “I would have done anything for him,” she said of the abuser. “I don’t remember feeling ashamed at first.”

She stressed that far from being enjoyable, this sinister manipulation is effective in ruining children’s lives, right up into adulthood. She compared the feelings some children have for adult abusers to Stockholm syndrome, the psychological condition where hostages develop warm, sympathetic feelings for their captors.

“You don’t know how to break free from it, either,” she said.

An information exchange way beyond leaflets

O’Carroll hosts his blog on the US publishing platform WordPress. He saw on social media that people have sent complaints about his site to the company, but WordPress has never contacted him, he said.

“The content of what Tom O’Carroll is writing does not constitute as an offence,” the UK’s Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre wrote in response to a complaint from child protection expert and former social worker Liz Davies, as posted on her site. “He is stating his opinion, and although distasteful he is entitled to free speech.”

His blog is part of an unsettling online universe of blogs and forums where adults air their attractions to children, an information exchange beyond anything the readers of PIE’s homemade leaflets could have dreamed of.

The sites, like O’Carroll’s, have no images. Users prod each other to remain within the law of their hosting server’s country.

“Do not advocate or counsel sex with minors,” read the rules of the BoyChat forum. “This rule does not extend to philosophical, political, or biological discussions. Therefore, discussing whether or not one should be able to have sex with a minor … is not a threat.”

From some posts, it is clear the author is close to a child’s family. They write of the nervousness of a parent’s approach, and the relief of learning the parent is only coming to thank them for watching or employing the child.

“I am around 90 percent sure there is something between us — that she sees me as more than just her friend,” a user on one forum wrote of a 10-year-old girl. “It's looking pretty obvious where this one is headed.”

Not all pedophiles share that sense of entitlement. There are people who acknowledge that they have sexual feelings for children, but recognize them as wrong. The Lucy Faithfull Foundation is one of a few groups offering confidential outreach to such people, so that they can manage their feelings without harming a child.

Those who have justified their impulses to themselves are harder to reach. Across these blogs and forums there is a strain of righteous anger, of adults who see themselves as victims of a society that fails to understand the nature of their impulses.

“Many abusers delude themselves to believe their behavior isn’t depraved, isn’t harmful and can be positive in a number of ways,” Findlater said. “Abusers groom themselves to believe it does no harm.”

This is true of some pedophiles, O’Carroll believes. He just doesn’t think he’s one of them.

“There have to be sanctions for those people who are wishful thinkers, and there are those people. There will always be people who do that,” O’Carroll said.

He agreed there is no way to know what pain an adult’s choices will cause a child in the future, how an adult’s intrusion might reshape the person the child becomes. It is the one point on which his language is anything other than certain.

“You just make a judgment as you do with anything else,” he said. “Many years later you may get a different impression. You may get an impression that you were wrong before that.”