In job-hungry Italy, neo-Fascists await young migrants

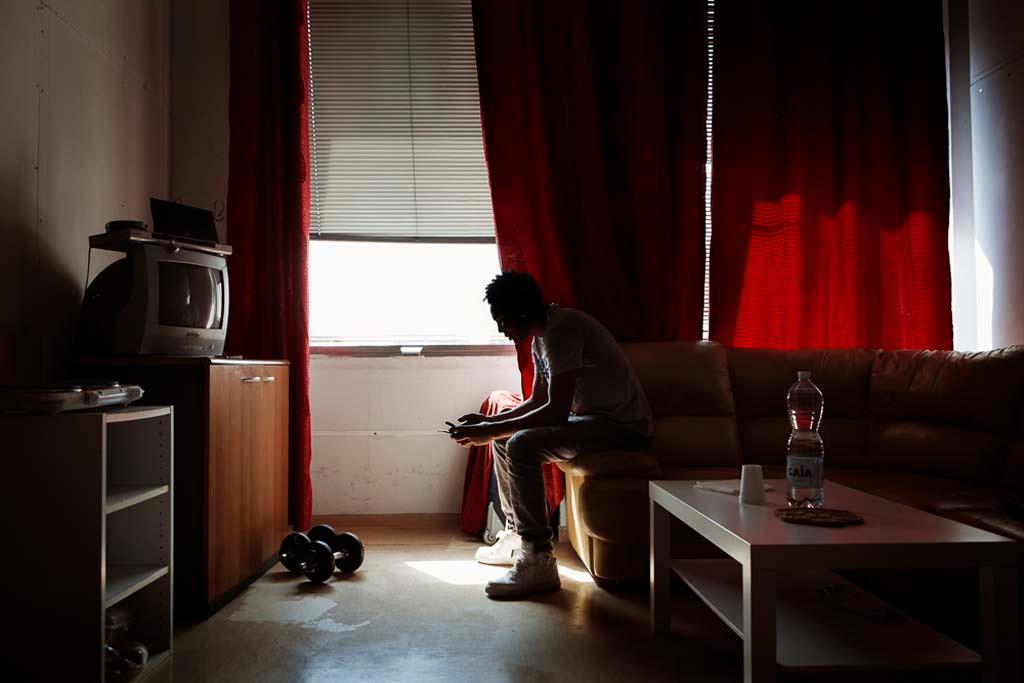

Abraham, 25 and unemployed, peers at his cell phone.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a special report on the global youth unemployment crisis, “Generation TBD.” It's the result of a GroundTruth reporting fellowship featuring 21 correspondents in 11 countries, a year-long effort that brings together media, technology, education and humanitarian partners for an authoritative exploration of the problem and possible solutions.

ROME — Their eyelids are heavy and their bellies are light. It’s just after dawn as 400 migrants huddle aboard an Italian naval ship, which rescued them after five days adrift aboard a packed, dilapidated raft in the perilous waters north of Libya. As they approach the Sicilian port town of Augusta, a few muster the strength to stand, peering across the turquoise water at the European continent that will soon be their home. Most can only crouch, faint smiles of survival and hope upon their lips.

From Eritrea, Sudan and Syria, these men and women have escaped the fate of more than 2,200 people who have died since June while attempting to cross the Mediterranean from North Africa, according to the UN High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR). In one weekend in September, as many as 850 died when three boats sank or capsized — familiar disasters since the Arab uprisings began in 2011.

Few opportunities awaited that year, which also marked a peak in the euro crisis, the start of Italy’s worst recession since World War II. And few opportunities await now, with unemployment at a meteoric rate, 44 percent among youth. So far this year, more than 100,000 migrants have been rescued off Italian shores. Most of them are young men and some are barely in their teens.

“Because we all look forward to working, finding a job,” says Terrence, 26, from Eritrea. “I have training as a geographer,” says Abu, 25, from Darfur.

“I have experience in construction,” says Rafiq, 30, from Syria.

This group files onto the wharf at Augusta. With mile after mile of sand and sea behind them, most of the migrants are eager to focus on the future, which at this moment seems bright. As aid workers hand out water bottles and flip-flops, a colder and more dangerous reception awaits beyond these docks.

Over the summer, dummies of migrants have been chained outside ports and train stations stretching from Palermo to Milan, with posters linking their arrival to the deteriorating labor market.

“We import slaves, we produce the unemployed,” they read, in the same font favored by Benito Mussolini. They’re signed by CasaPound, Italy’s biggest neo-Fascist movement, which has been linked to numerous acts of violence against migrants over the years. The vast majority of its members are young, and their numbers have been growing.

And they too want jobs. They too want futures.

A neo-Fascist without tattoos

One of them is Estella, a 25-year-old political science graduate with a four-month-old son. She hunts for bargains at a grocery store near Rome’s central train station, nestled in one of the most multi-ethnic neighborhoods in the Italian capital.

“I’m buying pesto… yes, this is the cheapest one. One euro and five cents,” says Estella as she peers at price tags through thick-rimmed glasses and blonde bangs. “Ever since I lost my job, I have to buy food day-to-day. Everything is more difficult when you have a baby.”

Until January, she worked for a government agency that studied, of all things, trends in unemployment. Her focus was youth joblessness, she recalls with ironic laughter.

“I’m not making this up,” says Estella, who, hoping to one day get her old job back, is using an alias.

With a sweet smile and hipster fashion sense, it might be difficult to peg her as a neo-Fascist who spends her weekends protesting outside migrant centers.

“Yes, I’m a CasaPound militant,” she says, “even if I don’t have any Mussolini tattoos.”

Moments later, several African men walk by in the grocery store, followed closely by a security guard.

“In this supermarket, there is a lot of security, because many people always steal food,” says Estella. “This supermarket is full of immigrants.”

It’s a short walk back to Estella’s home inside a former ministry building. For the past decade, almost 100 people from her group have been occupying it, “because we can’t afford proper housing, and the government doesn’t do enough for low-income Italian families,” she says. A flag with a red border and the black outline of an eight-sided turtle — CasaPound’s mascot — waves from the top of the eight-story building.

Inside, hallways are decorated with Leni Riefenstahl photography, nationalist slogans and the names of noteworthy Italians, from Dante to Mussolini. A wall display traces the life of American poet and notorious Fascist sympathizer Ezra Pound, CasaPound’s namesake.

Drawn to the movement while in college, Estella lives here with her baby and her 28-year-old boyfriend, a high-ranking CasaPound militant who is also unemployed. Inside their modest one-bedroom apartment, the air is thick with paint and plaster. A fellow member of the movement, a construction worker, redid their kitchen.

“We help each other out. We’re like a big family,” she says as she turns on the movie ‘Finding Nemo’ for her son. “We depend on each other, especially those out of work.”

Estella says she knew her job was at risk last summer when she became pregnant last year.

“I knew human resources would not want to pay for both a temporary replacement and my maternity leave,” she says. Dismayed, she did something drastic.

“I hid my pregnancy,” she continues. “It was my boss’s idea. She helped me keep it a secret.”

For five months, Estella wore baggy clothes, carried her purse in front of her belly, and made sure she was the first to arrive and the last to leave.

“That way I could hide behind my desk. And I’d make sure to go to the bathroom only when everyone had gone to lunch. Once I had to hold it for three hours.”

By November, the jig was up. “It got impossible to hide,” she says with resigned laughter. “It’s ridiculous. In the most important time of my life to have a job, they decided to let me go. At first I panicked. But I was motivated to find another job for my baby.”

Since then, Estella says she’s submitted roughly 100 resumes. She’s had offers, but with salaries that amounted to a fraction of her previous monthly paycheck of 1,300 euro, and to work double the hours.

“Now my unemployment benefits are about to run out in October,” she says. “I have to find something soon.”

‘They look the other way’

Abraham, a migrant from Eritrea, takes a jar of tomato sauce to the cash register of his neighborhood bodega. It’s only minutes away from where Estella lives, across from the Rome central train station.

“This costs too much,” he tells a familiar cashier in good humor. “I can’t keep coming back here if you keep raising prices.”

Abraham chuckles as he puts 1 euro and 30 cents on the counter, takes his sauce and heads home.

Like Estella, he is 25 and has an advanced degree.

“It’s in agriculture and animal husbandry: livestock animals, cows, goats, sheep, swine. Also beekeeping. And I speak four languages. My Italian is much better than my English,” he says with a rote fluency acquired after countless trips to unemployment offices. There’s one right on his street.

“There’s no way I’m going in there again,” he says. “Every agency in Rome has my resume. They don’t call, they don’t email me. Even in Italy, everybody is not equal. They give the first chance to the Italians, the second chance to the other white people, and the third chance – if there is one – to us Africans.”

Eritrean music gets louder as we approach Abraham’s building.

Like Estella’s, the complex once belonged to the central government. Now a squat, roughly 600 migrants call it home – their ‘palazzo’, which takes up an entire city block. The exterior is covered in austere reflective glass. In the foyer, three young men monitor who comes and goes.

“Every resident pays three euro per month to cover their salaries,” Abraham explains as we’re both waved through. “It’s the only rent we pay.”

He’s lived here since last October, when he and the rest noticed the eight-story building had been abandoned — a casualty of euro-crisis budget cuts.

“All we had to do was clip the locks,” he says. Offices were converted into apartments. Filing cabinets became dresser drawers. Desks became kitchen tables. “Since then, the government hasn’t complained. The water is still running. The electricity is on. They don’t know what to do with us, so they’re looking the other way.”

Handsome, six feet tall and with an athletic build, he could pass for a Ralph Lauren model. But to hide his identity and protect his family in Eritrea, he shies from cameras and insists on using an alias.

The elevators no longer work, so we walk the stairs to his studio apartment on the top floor. Inside, one of his two roommates is asleep after working all night. Doing what precisely, Abraham can’t remember.

“Something random,” he says. “That’s how we take care of each other. When one person finds work for a day, he shares the money with the rest. That is our culture. We are like brothers.”

It’s a long way from where he imagined he would be five years ago when he defected from the military in Eritrea, a former Italian colony which has been described by Reporters Without Borders as "a vast open prison for its people" with one of the world's worst human rights records. The country's government is running an indefinite conscription program, a UN investigation found, and Eritreans caught evading it face "on-the-spot execution."

“It’s like North Korea,” says Abraham, “because if they see you while you’re crossing the border, they shoot you with a gun. When I escaped it was at night, 1 a.m., alone in the forest. There were so many animals, like hyenas. And there were mountains. I had to hide from the people who listen for the sounds. It was life or death. At that time, to live means nothing. Only sacrifice.”

He eventually made it to Ethiopia, then Sudan, then through the Sahara, which was littered with decomposing bodies of those less fortunate. After arriving in Libya, at the time still controlled by Muammar Gaddafi, Abraham spent three months in a Benghazi prison before friends and family came up with ransom, he says.

Smugglers eventually brought him and 300 others to Italy. He qualified for political asylum and was sent to a migrant center in Rome where he lived for one year.

Since then he’s shuffled between the streets and squat houses, which in Rome alone number in the dozens, according to local aid workers. Though few are as big and as surprisingly clean as where Abraham now lives. Residents credit the guards for enforcing rules and making sure not just anyone can wander in off the streets.

“The guards are some of the few people here who have steady jobs,” Abraham notes.

A race to the bottom

Abraham manages to work from time to time — a day here, a week there — almost always under the table. The best experience came three years ago at the airport.

“I helped the technicians move and unload things. It was good and bad, because I worked illegally. They take advantage of you. When I worked more than eight hours they never gave me overtime. But compared to the situation in Italy, it was okay.”

Jobs off the books are at the heart of CasaPound’s rancor, members say.

“There are no jobs Italians won’t do,” Estella insists, “only wages they won’t work for. Italians would gladly do manual labor, and other jobs migrants do. But they’re underpaid. You can’t live decently like that. Immigration creates a sort of race to the bottom.”

Abraham agreed with some of her thoughts.

“She’s right, because there are so many foreigners here,” he says. While Northern Europe hosts many more migrants, Italy is the OECD country with the highest annual growth in its migrant population since 2000. An OECD report this summer showed the share of the foreign-born population nearly tripled between 2001 and 2011 to reach 9 percent.

“So if they took jobs, yeah, really, it makes the situation harder for Italians,” says Abraham.

But he notes that refugees — who make up 80 percent of the migrants who land in Italy, according to the Italian government — are left with few options.

“If she knew my situation in Eritrea, the real situation, she couldn’t ask me to stay home. Besides, Italy is responsible for its former colony,” he says, recalling that from 1890 to 1947, his country was occupied by Estella’s. He even wonders if the current government of Eritrea learned how to govern from Mussolini.

“It’s a military dictatorship, the same as Italian Fascists,” he says. “But perhaps only one percent of Italians know that Eritrea was an Italian colony.”

Estella is adamant that neither she nor her movement is racist. Her university thesis focused on the plight of the Karen ethnic minority in Myanmar, she points out. And CasaPound even has its own foreign-aid organization called Solid. Recipients are required to stay in their country of origin.

Its reputation for xenophobia and violence was cemented in 2011, when a Tuscan man who frequented CasaPound meetings went on a shooting spree in Florence, killing two street vendors from Senegal and wounding three more before killing himself. Estella says he was not a card-carrying member: “Not a militant, like me. He was just some crazy person.”

While such bloody episodes are uncommon in Italy, anti-immigrant sentiment is not. A Pew survey in May showed 80 percent of Italians would like fewer migrants in the country.

Where dreams become a mirage

Gemma Vecchio is an Eritrean who runs Casa Africa, a Rome-based migrant aid organization.

On a recent morning, she distributes day-old pizza from a bakery outside Abraham’s building.

“I understand why they leave, but I don’t know why they come here,” she says. “You know some of them pay 10,000 euro to traffickers? And why? To live like they’re homeless? Imagine if they invested that money in land in Mozambique, for instance. There’s growth there. Not here. The European dream is a mirage.”

Many young Italians feel the same way, leaving the G8 country en masse — about 60,000 every year, seven out of 10 taking a college degree with them.

While almost 400,000 graduates have left Italy in the past decade, only 50,000 similarly qualified foreigners have arrived, according to national statistics agency ISTAT.

Meanwhile, Abraham and Estella are here, and they’re desperate to make the most of it.

“Me, as a human being, I must work,” says Abraham. “I want to work, to live as everybody. Because to work means to know yourself. To be more confident. And I want to integrate with society, with Italians. I pray for this, when I eat, when I sleep and wake up.”

He makes the sign of the cross, and recites the Lord’s Prayer in Tigrinya, his native tongue.

“Our father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name …”

Nearby, just across the train station, Estella is putting her son to bed.

“Raising a baby is important to me, more important than having a job,” she says. “At the end of the day, I’m optimistic”.

She says she’s not religious, but she prays the same prayer every day.

“… Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread …”

“Fortunately I have a family,” Estella adds, referring to her partner and her baby, but also to her neo-Fascist movement. “A big, big family. For other people, it must be difficult.”

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.