It’s not easy finding peace in the world’s most dangerous megacity

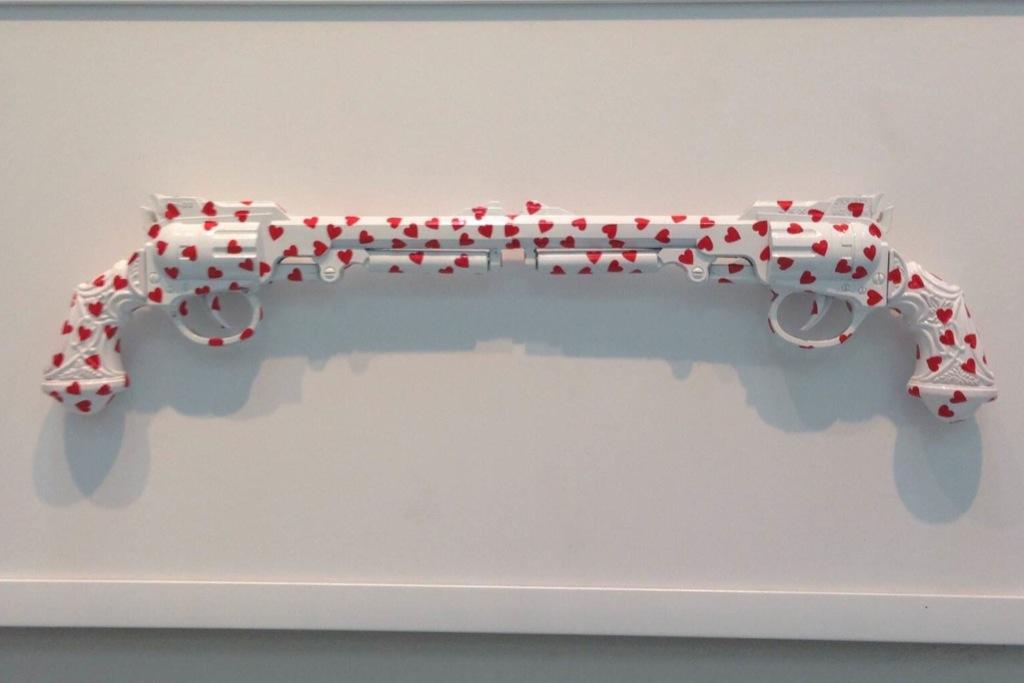

Local artists want to combat Karachi’s soaring rates of violence with images of peace.

KARACHI, Pakistan — In September, Foreign Policy dubbed Karachi the world's most dangerous megacity, claiming that the sprawling metropolis in which I live has a homicide rate that's 25 percent higher than in the rest of the world's largest cities.

The statistic isn't surprising to anyone who lives here.

In fact, part of my adjustment to living in Karachi again — I moved back last year after 13 years in the United States — has involved getting used to the cavalier way people talk about brutal violence. Dinner party conversations regularly revolve around the ransom amount for an acquaintance who's been kidnapped, or the latest person we know who was mugged at gunpoint.

I live in a rarefied strata of Karachi society — the estimated 10 percent of city residents who enjoy disposable income, flashy cars and highly-secured homes. But everyone here worries about violence and political instability, regardless of class. And no one is entirely removed from the threat: a stray bullet from a street fight, an argument with someone of the wrong ethnicity, or just being in the wrong place at the wrong time can get anyone robbed or shot.

So I was intrigued to learn that a group of local artists and civil society activists were planning an arts and culture event under the optimistic banner "Peaceful Karachi," or "Pursukoon Karachi." The three-day festival, held last weekend at public and private venues around the city, offered free exhibitions aimed at bringing city residents together to see — in theory at least — Pakistan's largest city at its best.

I imagined the experience was going to offer windows into the pockets of harmony we tend to ignore here in Karachi.

Instead, almost all of the events focused on creating idealized visions of what Karachi should be. At one event, NoorJehan Bilgrami, one of the festival's organizers, asked a small audience to suggest ways to make Karachi a more peaceful place. Young artists illustrated their ideas — more secular music! more public parks! — on a stretch of butcher paper.

The organizers proclaimed art a tool for promoting peace, even as news filtered in about Taliban bombings in the city's Ancholi district.

Some attendees described the festival as inspiring, giving them hope for their beleaguered city. Critics said it was just a chance for the elite to imagine a reality only those with means could experience.

I have to agree with the critics: The conversation will likely end with the festival. None of the auditoriums were full. None of the events I went to had more than a few hundred participants — in a city of between 18 and 24 million people.

But at least one thing will remain. As I left the private Arts Council grounds where some of the events had been held, a wall stretched out in front of me where participants had painted "messages of peace."

My favorite showed a simply-drawn figure throwing an oversized gun into a trash can. Now that seems like a good place to start.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!