This Indian city is on a quest to get rid of shantytowns. Turns out that’s not very easy

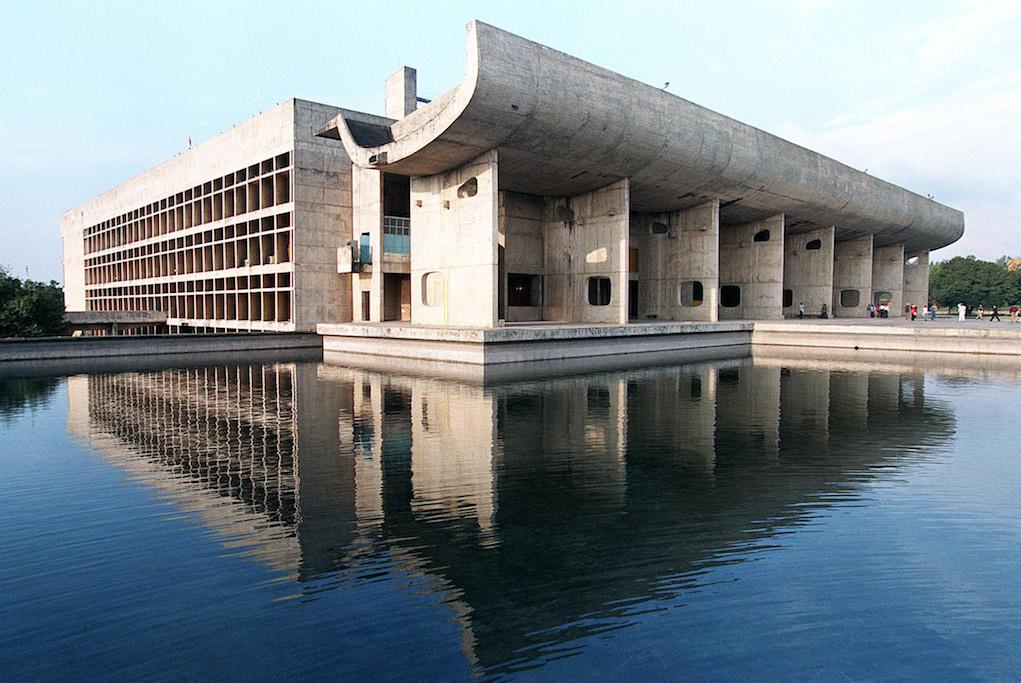

CHANDIGARH – JANUARY 9: Le Corbusier designed the impressive Legislative Assembly building in Chandigarh, in his attempt to enable people from all levels of society to “live in dignity.” But his brief apparently didn’t include housing for workers.

CHANDIGARH, India —On May 28, Ayodhya Prasad rested on a woven cot after a long night of work, wondering when the mint-green brick walls around him would finally crumble. The newspaper that he checked anxiously every day said the city had scheduled the demolition of his neighborhood for June 2, but the plan had already been delayed twice, and his family of six had yet to secure a new home.

For about two decades the 50-year-old market vendor has lived with his four sons and daughter-in-law in a one-room hut in Chandigarh, in northern India. Designed in the 1950s by the famous Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, Chandigarh — a pleasant metropolis of green gardens and minimalist buildings — was the first city planned in India after the country achieved independence in 1947.

But Prasad lives in Bapu Dham, a crowded shantytown that has sprung up within its borders, in part because Le Corbusier’s plans didn’t include housing for laborers. The Prasad family has become accustomed to life in this working class community, where the average family income is 10,000 rupees (about $200) per month.

“We’ve been here for a while so we like it,” Prasad said, bleary eyed from the night shift.

Things around him are changing quickly.

In 2006, the city introduced a scheme to rehabilitate 18 slum areas by constructing more than 25,000 new apartments for poor families. The project was designed to provide low-cost housing to thousands of people who currently contend with faulty water lines and unreliable electricity in these informal settlements, with the added benefit of freeing up valuable land for development.

“We’re providing the social infrastructure required for living — for high quality of life for every resident of Chandigarh,” said Sumit Kaur, chief architect at the city’s Department of Urban Planning.

But the plan is hardly foolproof. Many families who will soon lose their current homes in the demolition phase haven’t received new ones. Others have resettled in the new buildings only to find that their workplaces and children’s schools are now more than an hour away, disrupting livelihoods and lifestyles.

“This has been going on in driblets — they fix a new deadline, they plan demolition, but there is no analysis of the complexity of the relationship between work, housing and other features,” said Madhu Sarin, the former mayor of Chandigarh who has analyzed the city’s architecture and planning.

Throughout May, the Bapu Dham neighborhood full of small huts with corrugated metal roofs and narrow dirt alleys buzzed with transition. Families who had received housing were busy shifting their clothes and cooking vessels to their new homes in Dhanas, a neighborhood on the opposite end of the city. Others were stalling to vacate their homes, trying to navigate longer commutes to work or school.

“It’s going to be different now,” said Roshni Kumar, a petite housewife who was getting ready to move with her husband and two children in the next two days. “But it will be good.”

The 28-year-old said the summer season means the water taps often run dry and the electricity is prone to going out during the hottest part of the day. The families in Bapu Dham share both public restrooms and communal water taps — carrying buckets through the alleys for washing clothes and dishes. In Dhanas her family will have their own bathroom and regular power. The city also built schools and markets for the new complex, funded by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation.

Meanwhile, Prasad said the government had never approved his paperwork, despite promises from candidates who came door-to-door during election season to talk about the new apartments. Though a new apartment in Dhanas would make it difficult for him to commute to the market for work, he and his sons have been appealing to the local housing board to secure some sort of shelter, and are still awaiting a response.

“They’re just making an excuse,” he said.

Sarin, the former mayor, said these broken promises characterize Chandigarh’s history with low-income housing. Labor unions had been trying to negotiate for at-cost plots of land close to their jobs since the 1970s, but were slowly pushed to the relatively messy settlements along the city’s outskirts.

Even with the new housing scheme, families are struggling to pay the fees to secure and set up their new homes, small rooms that are 20 feet long and 12 feet wide. Kumar said she and her husband, an auto rickshaw driver, had invested almost 70,000 rupees (about $1,200) in the new flat, much of which was borrowed from other family members.

While former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, on a visit to Chandigarh last September, suggested it could become India’s first “slum-free city,” Sarin said the city missed several opportunities to set a precedent for the rest of the country on how to create housing for the working class.

“We could have offered dignity to the poorest of the poor,” she said from her spacious home, one of the first built in the city. “Chandigarh, in addition to being a new capital, was meant to lay a foundation for architectural planning in India.”

Chandigarh's early design wasn’t an oversight, said Vikramaditya Prakash, a Seattle-based architectural historian, urban planner and author of “Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier: The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India.”

He said Chandigarh had been built as an administrative capital rather than a normal city. Le Corbusier and the team of urban planners had been told only to plan for government workers. Nevertheless, informal settlements existed from the very beginning of Chandigarh’s development, when the construction workers and their families moved close to the sites.

“There was no provision made for workers,” Prakash said. “The city was never designed to be a proper full-fledged organic entity.”

Families like the Prasads are bearing that burden. By mid-June their home was still standing, though many more homes in the neighborhood had been demolished. Still on edge, Prasad said he was searching for alternative housing in other low-income areas, while still holding out hope that the government would approve their documents, which he said included the necessary voting records and proof that his family had lived in the city since at least 2006.

Meanwhile, Chandigarh’s chief architect is optimistic. She said almost 8,000 apartments have been constructed and allotted to families, and the city has incorporated new housing provisions to support the working class, like requiring that 15 percent of each new development be reserved for low-income housing. And their work has earned them accolades from the government, including a national award for “City with the Best Planned Habitat for Urban Poor.”

“Chandigarh has taken strides,” she said. “I think we’re doing a lot of things worth emulating.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!