Guns, knives and rape: The plight of a gay Ethiopian refugee in Kenya

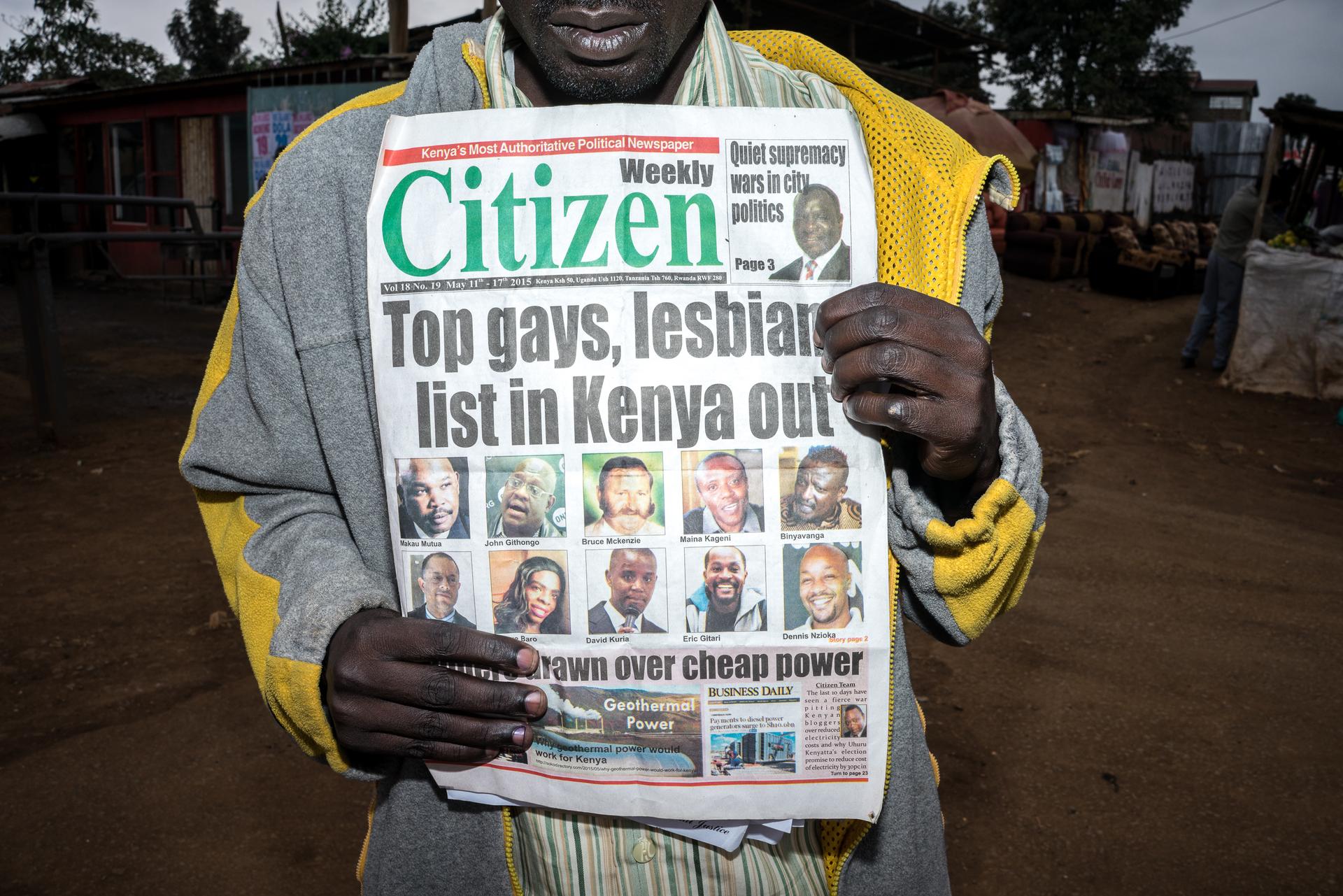

Vincent Kidaha, President of Kenya’s Republican Liberty Party, holds a copy of a newspaper headlined "Top gays, lesbians list in Kenya," that was published in May of this year. His organization contacted the people named inside with offers to rehabilitate them.

NAIROBI, Kenya — Ibrahim became aware of his homosexuality in high school, living in the city of Adama, 50 miles south of Ethiopia’s capital. He said he felt attracted to boys, but nearly always kept those attractions secret.

“I was told that I am mutant or something, and I couldn’t do anything to express who I am because it might be dangerous,” he said.

Ethiopian society has long been staunchly homophobic, but in the 2000s, anti-gay leaders drove the subject into the public spotlight. In 2007, the Pew Global Attitudes Project reported that 97 percent of Ethiopians said homosexuality is unacceptable — the second-highest rate of non-acceptance in all of the 45 countries surveyed at the time.

What was responsible for all this homophobia?

“Religion,” according to Ibrahim. “As you know it’s also one country that follows the [Ethiopian] Orthodox [Tewahedo] Church. It is so conservative on religion. It completely rejects our identity. It’s preached by the church and everywhere, even the government,” he said. “It was so harshly spoken of by the church I was not even open (out) at that time.”

And it only got worse as Ibrahim entered adulthood. In 2008, many of the nation’s foremost religious leaders, including both the Catholic and Anglican archbishops, denounced homosexuality in a letter and called on lawmakers to ban it outright in the nation’s constitution.

“For people to act in this manner they have to be dumb, stupid like animals,” Abune Paulos, patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, was quoted as saying. “We strongly condemn this behavior. They have to be disciplined and their acts discriminated, they have to be given a lesson.”

Last year Dereje Negash, chairman of a religious group affiliated with the same Orthodox Church, told The Guardian he wanted Ethiopia’s government to criminalize homosexuality further still.

“I believe I have been given a task by God to do this,” he said.

The church of Negash and Paulos is the same church to which Ibrahim’s family belonged. Perhaps that is why, when some of Ibrahim’s coworkers spotted him socializing at a club known to be a gathering for gays, they told his father the news.

His father then called Ibrahim and asked if it was true.

“He told me, ‘If so you’ll get the consequence — I’ll kill you or I’ll send somebody. You can’t adulterate my family, my name and my religion.’” Then and there, he disowned Ibrahim completely and forever.

The abuse carried over into Ibrahim’s workplace.

“When I go the next morning to my job, the face of the whole office, the boss, the managers, they were offensive, even disgusted. Some of them challenged me directly — that I am bushdi, in our language.”

Ibrahim left his job, but that’s when the abuse turned into violence. On at least two occasions, he said, men came to threaten him, telling him to leave his Addis Ababa neighborhood.

Then, on the evening of April 20, 2014, “Guys came to me having a gun and putting the mouth of the gun on my head,” said Ibrahim. “Then they told me ‘This is the last time to run — otherwise we will kill you.’”

The next day Ibrahim packed some of his things and hid in a hotel. Within a week he was at the airport trying to buy a one-way ticket out of his homeland. He thought about fleeing to Somalia, and considered other countries as well, but the only place he could go without having to apply for a visa in advance was Kenya. And so, he booked a flight to Nairobi where he hoped to apply for asylum to leave this part of the world forever.

But his timing was unfortunate. In an attempt to appear to be doing something in the wake of a bungled response to a terrorist attack on Kenya’s Westgate Shopping Mall, Kenya’s government had recently ordered all refugees to leave the cities and return to the primary refugee camps in Kenya’s north: Dadaab and Kakuma.

At the advice of an official at the UN Refugee Agency, Ibrahim boarded a bus with other refugees to Kakuma, unaware that he’d soon face homophobia rivaling the very horrors he had fled Ethiopia to escape.

The camp

Home to more than 180,000 refugees from South Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia and elsewhere, Kakuma wasn’t a melting pot but a pressure cooker — steaming with tension from different groups of desperate people who didn’t get along.

Perhaps no group was regarded with more disdain by the others than the gay, lesbian and transgender population, many of whom had arrived recently after fleeing homophobic fervor in Uganda. Some of them say they faced far worse discrimination in Kakuma than they had back home, where a new law momentarily prescribed life imprisonment for those who engaged in homosexual activity on a “serial” basis.

Other refugees would speak ill of Ibrahim and the other LGBTs there. He said the worst were the Somalis and the Sudanese.

Ibrahim recalls a fight last summer in which another camp resident attacked a Ugandan transgender.

“While the Ugandans went to report it to the police, I was alone in my tent,” said Ibrahim.

That’s when the violence came to him.

“The Somalis … learned that I was gay. They came with (a) sharpened thing and put it on my leg and they cut me here,’” he said, pointing to a spot below his knee. “And they told me in the next round they would cut my penis.”

“I had no option,” Ibrahim said. “I sold some trousers with which I came from my place, then I paid transport to come back to Nairobi.”

For the second time, three months after he arrived in Kakuma, Ibrahim was fleeing for his life. And just like the first time, instead of safety, what he found was even more chilling than before.

“I used to (hear) that people are raped, but I never thought I would face in my life to be raped,” begins Ibrahim about the night he was chased out by his Kenyan landlord from the apartment he rented in Nairobi.

“The landlord came to know that I was gay because of the people coming to visit me there. It was midnight and he chased me away,” Ibrahim said.

He became instantly vulnerable as people in the neighborhood saw that he was homeless and alone.

As Ibrahim left the building with some of his things that night, two men approached him.

“They told me just to go, follow them, otherwise they will kill me if I shout. They harassed me, assaulted me,” he said. The night was January 25.

Ibrahim describes how the two men took turns raping him in a room in Eastleigh. “It was so heartbreaking…the scars are so hard. I can’t speak it out in words. They were bigger in size than me and they were stronger” he said. “I tried to struggle. I lost my strength after that.”

“It was heartbreaking,” he said. “My heart bleeds. My heart bleeds and I couldn’t tell anybody.”

When they finished, the two men let Ibrahim go with a warning to keep silent. The next day he told a friend who brought him to a medical clinic where doctors examined him. Ibrahim thought about seeking justice against his assailants, but didn’t know how he could safely approach the police.

Soon, however, the police would come for him.

Persecution in Kenya

On a sunny morning in February, Ibrahim was on his way to meet a GroundTruth reporter at a Nairobi café when he was arrested by police and locked in a small security hut outside a strip mall.

The charge? Dressing like a woman. He’d been doing so to disguise himself, Ibrahim said.

Outside the hut a policewoman stood guard with a rifle. After about 20 minutes a senior officer arrived, refusing to identify himself. When asked why Ibrahim was detained, the officer responded in a serious tone.

“We have to follow the law,” said the officer. “Don’t try to wear a lady’s attire while you are a man in Kenya,” he told Ibrahim. “It is illegal.”

It isn’t, of course. But in Kenya, a gay man dressed as a woman stood out markedly.

As the minutes of his detention ticked by, Ibrahim became increasingly worried about what the police would do with him.

“I’m scared,” he said. He reflected on the long, tragic history that brought him to this moment — an LGBT refugee in a foreign country whose language he does not speak, whose laws he does not know.

“I have been chased away form my home place in coming here. I have been chased away from the camp called Kakuma, being threatened for dead. Here I’ve been raped and given a death threat.”

After an hour police brought Ibrahim to a nearby jail. There he waited while the UN Refugee Agency worked to confirm his identity. He was released that evening, about 10 hours after his arrest.

In the following days, Ibrahim rarely ventured out of the home he shared with a transgender friend of his.

He said people in the new neighborhood came to realize he’s gay.

“Some of them ignore us, just spit on us.” he said. “We keep our urine here with some package like that because in the daytime it’s hard, you see. The eyes of people also, they’re punishing us. Some of them speak the word out loud: shoga (Kenyan Swahili for gay).”

In early April, Ibrahim finally received a bit of good news: he learned his request for asylum had been approved. Pending security and background checks, he would soon be resettled in the United States. But the resettlement process is long, and unable to venture safely about in the city much less find a job, he can do little else but wait and reflect.

“I thought that when I run away from my place that I would survive, at least,” said Ibrahim of his flight from Ethiopia to Kenya. “But similar things have happened here also. People are pushing me, insulting me and giving me death threats. I was thinking of, what you call it — suicide.”

He said he hopes the US will offer him something he’s only ever dreamed of. “A place with LGBT groups, where I can practice my freedom as a gay person,” he said. “Also to have my own partner and continue my previous life again. That’s my wish. Without identity, you’re almost dead.”

“I feel a loneliness, you see? I am missing my father, even my brother, sister and mama, they totally stopped calling me. Like saying, ‘Happy birthday,” said Ibrahim. “They are ashamed by me. The only one calling me was my dad and as I told you, rather than love, he usually threatens me.”

After everything, Ibrahim said the most haunting is being unable to practice his faith.

The morning he was arrested by police, Ibrahim had stopped at an Orthodox church across the street to pray. “One of them knew that I am gay from Kakuma,” he said. “They chased me away from the gate. I couldn’t pray even.”

This story is the third in a series on LGBT rights in East Africa, produced with support from the Galloway Family Foundation. Read the first story, "Anti-LGBT groups are making inroads across East Africa," and the second story, "Inside the nightmares of Africa's LGBT refugees."

This story is presented by The GroundTruth Project.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?