Forget filial piety. Young Chinese are fed up with the old

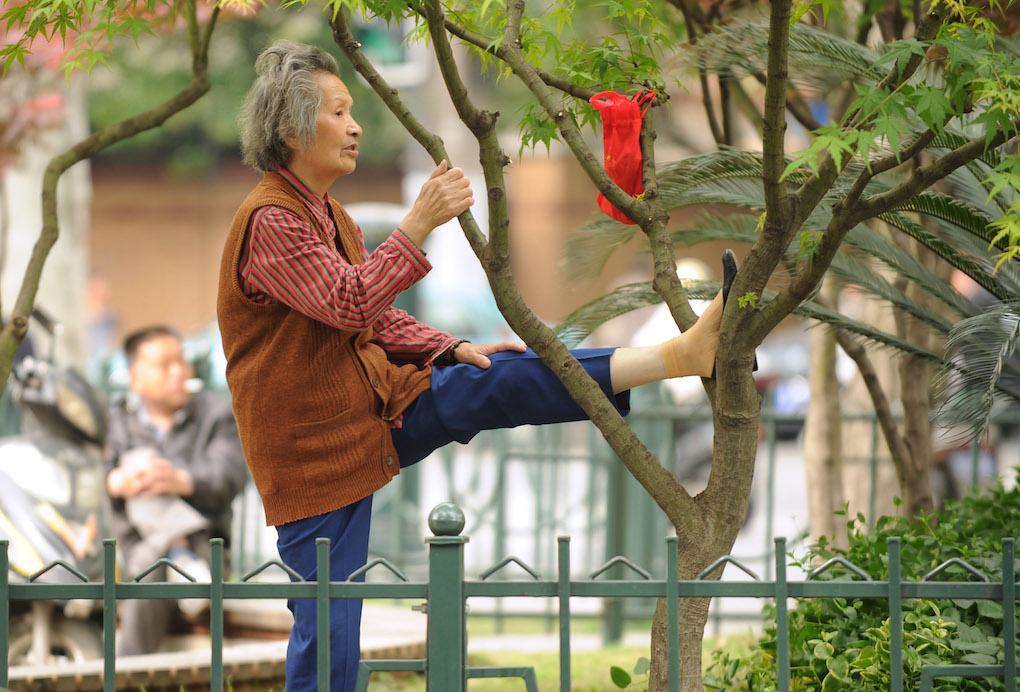

An elderly woman stretches against a tree in a Shanghai park. “Dancing grannies” in parks have irritated some young Chinese so much that they armed themselves with water balloons and made it rain; the stubborn grannies erected umbrellas.

BEIJING, China — An ancient Confucian scholar once wrote approvingly of a magistrate who tasted his own father’s feces to check for illness, an exemplar of filial piety.

Three decades of Maoism failed to uproot the ancient sage’s philosophy, but nowadays some seniors can count themselves lucky to get a bus seat.

In Wuhan, where such seats are prioritized for the pregnant and elderly, a dispute between an earphone-wearing youth, who had poached one, and a group of silver-haired passengers who objected, erupted into a farcical scene of shouting, pushing and slapping, all captured on a viral cell phone video.

Condemnation was swift — though most of it was directed at the elderly. The use of violence was particularly galling to some: Why, they wondered, should the young volunteer to cede seats to those with the strength to threaten or even beat them?

The story, and others like it, illustrate problems that have long existed in China, but are increasingly worrisome as its huge population ages, amid limited public resources.

A much-cited recent poll in People’s Tribune magazine lists a lack of morals and a “bystander” attitude among the country’s 10 worst social problems.

Gridlocked roads, desperately overcrowded subways and oft-delayed flights have made commuter rage a common part of life in big cities, but tension between the generations is particularly high, sometimes leading to extreme consequences.

Another bus seat altercation this month, in Zhengzhou, central China —involving an elderly man, several passengers, and the seat’s much younger occupant — resulted in the man, in his 60s, collapsing. Despite attempts to revive him, he reportedly died shortly after.

Again, the debate centered on whether the youth was really responsible for the man’s death, and if traditional respect for the elderly was in decline. “The old, in Chinese history and culture, have always been the standard for morality,” says Professor Gong Fangbin of the China National Defence University. “When this group shows signs of corruption, people take it as evidence of all of society’s moral downfall.”

Indeed, Confucian teachings say the old should be respected — though they, too, must behave according to the superior moral principals.

Many older people instead are setting what seem to be dismaying examples.

One familiar scenario involves a truck overturning on a highway, perhaps injuring the drivers, only for hordes of villagers — old enough to know better — to descend on the scene to pillage the scattered goods, be they watermelons, grapes or fish.

Whether these ugly scenes show desperate scavengers or greedy opportunists, the lawlessness and indifference toward human life are shocking enough that the sight of a policeman drawing his gun to stop a geriatric orange thief is almost unremarkable.

It’s said that China’s over-50s may have survived the poverty, violence and political upheaval of the Mao-Deng years, but their values did not. Their revolutionary ideals were cast aside after Mao, then youthful liberalism was extinguished under Deng.

To the elderly, their children have never “eaten bitterness” like they did.

Instead, many grew up in cities, lusting for cell phones and mistresses rather than glimpses of Chairman Mao. The fabled three “must-haves” are no longer “two rounds and a sound” — bicycle, clock, radio — but the bachelor essentials of “three 180s” — RMB180,000 salary (about $30,000), 180 square meter apartment (about 1,900 square feet) and 180 centimeters tall (about 5' 10”). The marriage market has become a meat market. No money? No honey.

The young, meanwhile, are under intense pressures of their own. Due to the 1979 one-child policy, China’s retirees are expected to make up a third of its population by 2050. Most families, many households even, are “4-2-1” — four grandparents, two parents, one child. Without social security, the latter can be viewed as the family’s sole pension.

Thanks to traditional preferences, those single children are predominately male, meaning 34 million Chinese men also face perpetual bachelorhood. In order to lure a mate, young men need to find a good job in an intense job market, find the money for an apartment and a car, then quickly sire a child and start saving. Alternatively, they will have to endure their parents’ disappointment and be labeled "diaosi" (literally “wire dick”or loser).

Indeed, the stage has long been set for some explosive tensions.

Ironically, Confucius, once condemned to be destroyed along with China’s feudal culture, has now been rebranded to front China’s floundering soft-power institutes.

One peculiarly Chinese battleground has been the public spaces where retirees gather regularly for morning and evening dances, with dozens singing and swinging in time to music varying from Mando to Euro-pop, though always loud enough to fall on the deafest ears.

For the 100-million or so “dancing grannies,” this is their hard-earned leisure time. For those who appreciate neither the moves nor the noise, it’s an encroachment on what little space or time they have. (For the record, China does have municipal regulations on “anti-social behavior,” but as ever, no one is apparently willing to enforce them.)

In Chengdu, residents armed themselves with water balloons and made it rain. The stubborn grannies erected umbrellas.

In Wuhan and Changsha, the critics reached for human excrement, while those in Wenzhou decided to fight fire with fire, blasting whole troupes with the sound of car alarms.

One enraged Beijing man even unleashed the hounds on a stubborn group, before firing a shotgun in the air. He was arrested; the band played on.

The whole furor prompted one news portal to ask: “Did the old get bad, or did the bad get old?”

In the article, the author argues that the disruption caused by the civil war, Anti-Rightist Movement, Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution — where normal society effectively ceased — damaged people’s identities at a crucial stage of their development. Old orders were turned upside down; intellectualism became literally a foreign thing. Those raised on scarcity became used to stealing and hoarding, for example –a generation raised “on wolf milk.”

“They received a bad ethical education, both from society and from school,” says Professor Xiao Qunzhong of Renmin University’s Philosophy Department. During the Cultural Revolution. “People persecuted each other, even their own mothers, while their school education was completely absent.”

An editorial in nationalist tabloid Global Times was one of several to refute this, calling the Zhengzhou bus case “an isolated incident” which had shown up “the dark side of Chinese society.” The author used the same rationale as his critics — “Many of today’s old people have experienced more difficult times than today’s young” — to argue the opposite point: “We need to show more understanding of some older people’s behavior that may not look quite acceptable today … younger people need first of all to keep a humble approach in dealing with older people.”

Calls for “respect” were again heard after the China Youth Daily published controversial photographs of hundreds of students at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People sleeping through a speech delivered by 92-year-old academic Wu Liangyong. While his audience dozed, Wu, who needed a companion to aid his ascent to the dais and stood with the help of a cane throughout, narrated experiences of his hardship during World War II and the Cultural Revolution.

This was grist to the mill for anyone looking at the youth of today and seeing only fecklessness and indifference, although it later emerged that many of the audience were disgruntled students bussed in by university officials to fill seats, leading one commentator to suggest, “Don’t force students into lectures.”

Back in Zhengzhou, some octogenarians have taken to standing at bus stops, appealing to peers to give up their seats for hard-working young commuters.

It’s a rare gesture of hope.

Just days ago, after being denied a seat on a bus full of college students in Baoding, Hebei, an old man got out and held up the vehicle for several hours, declaring, “No one leaves!” The students later claimed that the man had refused several seats that were not to his liking.

The incident seems emblematic of a situation where the rules appear to have broken down. With neither side willing to listen to the other, all progress must halt. Everyone is made to suffer.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!