ExxonMobil fights malaria in Cameroon against backdrop of climate change

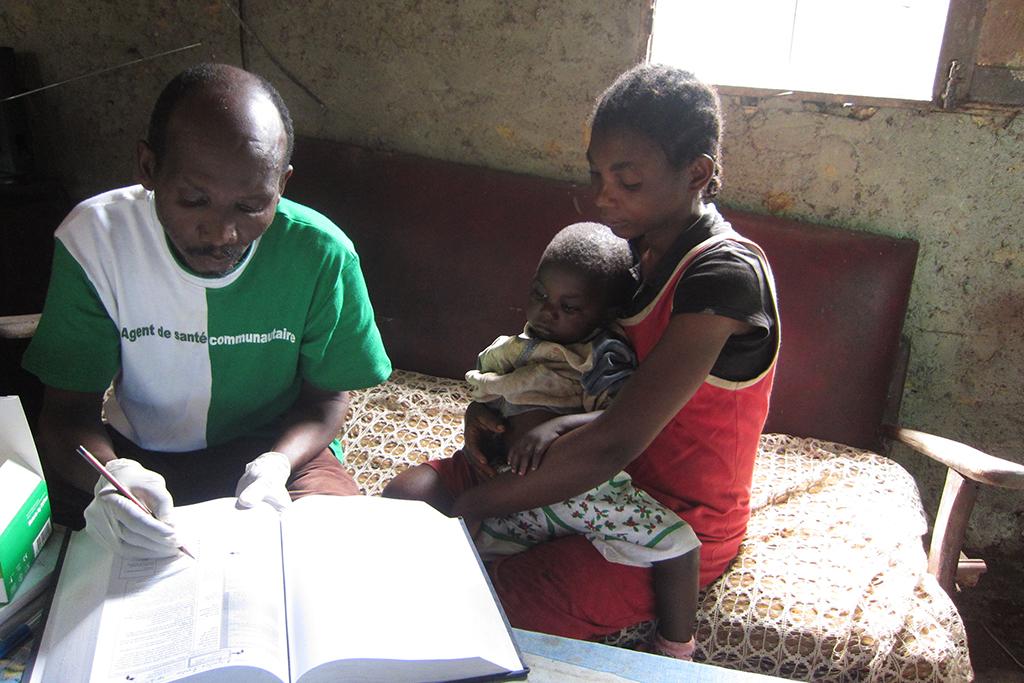

Community health worker Paul Obam takes a medical history of baby Henri Ayimbo, whose mother has brought him for a malaria check.

LOLODORF, Cameroon — Just outside this small crossroads town, in an isolated village in the lush jungle, there is a neatly lettered green-and-white sign posted with an arrow and the following words in French: “The community health worker is here.” Under that are logos of various health organizations, plus one you might not expect: ExxonMobil.

Follow the arrow down a red-mud road past some tin-roofed, wattle-and-daub homes, and you end up at the house of Paul Obam. He has been trained in malaria diagnosis and treatment by a nongovernmental organization, or NGO. In his open-air living room, Obam has a plain wooden box with everything he needs to prevent malaria deaths: a thermometer, rapid diagnostic tests, effective drugs.

In August, 32-year-old Albertine Mbouambo came in with her two-year-old son, Henri Ayimbo. Years ago Mbouambo had lost two children to malaria because she had not taken them for diagnosis and treatment soon enough. So on that August day when Mbouambo noticed that Henri felt hot, she acted quickly.

Obam confirmed the fever, took a history, and opened up a rapid diagnostic test for malaria. No malaria, he was able to reassure Mbouambo. But he was not sure what was causing the fever, so he suggested a visit to a government hospital down the road.

Obam is the face of a public-private partnership, or PPP, between one of the world’s largest companies, ExxonMobil, and hardworking local chapters of several international NGOs. ExxonMobil provides funding and oversight, while Cameroonians at the NGOs train health workers like Obam and provide them with diagnostic tools and treatment.

NGOs in partnership with ExxonMobil also run public education campaigns, distribute bed nets to stop mosquitoes that carry malaria, and work on vaccines. There is even a project that uses soccer drills to teach young people that malaria is preventable and treatable — important in a country where many just accept it as a fact of life.

According to ExxonMobil’s figures, the company and its foundation have spent more than $120 million over the past decade on the fight against malaria in African and Pacific Rim countries, much of it through PPPs. The company estimates it has helped an estimated 105 million people, distributed more than 13 million bed nets, and trained 355,000 health workers.

Such PPPs are becoming a more widely used way to fund health projects. Sam Worthington, head of a consortium of NGOs called InterAction, says that in the last 15 years, NGOs have gone from critiquing the private sector’s role in health and development programs to working with them in “shared value” projects. Some projects include US government money through USAID, he says, but more are just the NGO, the private partner, and local or national host governments.

ExxonMobil’s malaria partnerships may look like a win-win situation for Cameroonians and the company. But there are critics who say that through its production of fossil fuels, ExxonMobil creates problems by contributing to climate change. And climate change has health effects that may even include an increase in the incidence of malaria.

“You’re in this game of do you ask them to take a holistic view of public health, which goes against their business, or do you take what you can get?” asks Andrew Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists, an organization that has accused ExxonMobil of spreading disinformation about climate change. And some critics say the company is getting a lot of good public relations for spending just a pittance of its annual budget. Overall, the company’s efforts to combat malaria show that even a well-run PPP can have a complicated balance sheet.

Choice of malaria

Start with ExxonMobil’s decision to focus on malaria.

“You do it because it’s the right thing to do,” says Suzanne McCarron, head of the ExxonMobil Foundation, the corporate-giving arm of ExxonMobil. “But also it makes very good business sense.”

Doing well by doing good — that’s an axiom of many PPPs. And malaria is a big problem in Cameroon, a nation of 22 million people. According to the World Health Organization, there were 3.7 million cases of malaria in the country in 2012, 12,000 of them fatal. Most of the deaths were in children under 5, making malaria the nation’s leading killer in this age group.

ExxonMobil has a pipeline in Cameroon that brings oil from Chad to the Cameroonian port of Kribi. It also has massive pumping and production facilities in several nearby countries. About 10 years ago, ExxonMobil began a smaller-scale malaria program, launching avoidance, detection, and treatment projects among its own employees. Eventually the company decided to expand those projects beyond its own workforce.

“We have a very large business in sub-Saharan Africa, and it was very apparent to us the massive burden that malaria was putting on the communities where we operate, and also the countries and the entire region,” McCarron says.

Indeed, at the beginning of ExxonMobil’s pipeline project in Cameroon, the World Bank estimated that malaria was a $12-billion-a-year drain on African communities.

The ExxonMobil Foundation now has three main missions: fighting malaria, promoting education, and creating economic opportunities for women. But the choice of malaria has some aid experts wondering. One ideal for giving aid is to do a needs analysis, asking what is needed here? NGOs and governments commonly start their projects that way. But look at a list of current PPPs, and it is clear that they tend to focus on what the company needs: a healthy workforce, a good working relationship with the government, and good public relations.

For the malaria project, Gregory Adams, director of aid effectiveness at Oxfam America, asks: “Are there other public health needs that aren’t being met because they have less of an effect on ExxonMobil’s bottom line or work force? That’s an important question to ask, and I think it’s difficult to know the answer to that.”

“It’s important to have communities that are healthy,” the ExxonMobil Foundation’s McCarron says.

One of the decisions ExxonMobil has made is to focus one of its diagnosis and treatment programs along the pipeline. Dr. Etienne Fondjo, head of Cameroon’s National Malaria Control Program, is very happy to have the project there.

“The government alone cannot address the problem of malaria today, because the challenges are many,” he says. His only disappointment: His home village is miles away from the pipeline, and there is no free care there. ExxonMobil says that it is looking into expanding the reach of the program, and that it has other education programs that serve the whole country.

The company has also shown it is capable of something that is important to its NGO partners: flexibility. Recently, community health workers like Paul Obam reported back to the main NGO supporting community health workers along the pipeline, the Association Camerounaise pour le Marketing Social (ACMS), that they had a problem. Despite the free malaria care they offered to children, they were losing credibility in the community because they were not offering services for two other big killers of children: diarrhea and pneumonia. ExxonMobil agreed to expand the scope of its program.

“When you promote better systems in the health care delivery system overall, you are bolstering the fight against malaria,” McCarron says.

The NGOs ExxonMobil has chosen to work with — including global powerhouses Jhpiego, PSI (parent of ACMS), Malaria No More, and PATH — have years of experience, stellar reputations, and strong offices in the United States. They are nimble and smart. And as any development worker will tell you, they have the most important attribute aid agencies can have: Their in-country offices are run by locals who know their communities and are comfortable there.

In Cameroon, the company has been careful to include both the local and national governments in the planning and evaluation process.

“The partnership with ExxonMobil is essential,” says Cameroon’s minister of public health, Andre Mama Fouda.

“With the support of the private sector, we can accelerate the fight against malaria,” he adds.

The public health ministry and the National Malaria Control Program oversee ExxonMobil’s PPPs. The head of the control program says he does not characterize ExxonMobil’s PPP as a good or a bad thing, but as a necessity.

“The government alone will not be able to achieve this goal,” says Fondjo.

Program sustainability

One of the key factors for a successful PPP is sustainability. The global health world is littered with projects started, then abandoned as funders lost interest. Visit almost any country in sub-Saharan Africa and you will see schools built without ongoing funds for teachers, and medical clinics without staffing or supplies.

That is why Andrew Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists asks: “Even if Exxon does this work now, how long are they going to continue to do it? Are they willing to do it for 20 or 30 years? Is that in their corporate interest if they decide this isn’t where our major production area is now, or we’re going to move to a different region or a different kind of business model? They’ll drop it, and then what happens?”

Exxon says it will be there.

“When we commit to a certain area, we stick with it,” McCarron says, pointing to the Foundation’s 10-year support of malaria eradication. “We’re investing. We’re not just grant-making. We’re trying to make a difference.”

Though the malaria grants are year-to-year, leaders of four representative NGOs are confident that so long as they can continue to show ExxonMobil that there is a need, and that they are getting good results, ExxonMobil will continue to fund them.

One reason, says Cate O’Kane of PSI, is that if they think of it as their bottom line, they will be in that business for longer.

“These are for-profit companies,” she says. “They’re not going to keep doing things if it’s not working for them.”

Right now less than 5 percent of PSI’s budget comes from private companies, an amount she hopes will rise in the face of flat-lined or even declining dollars from the big international funding agencies.

“The nice thing Exxon has done is they’ve decided to take a disease and not stray from it,” says Mark Allen at Malaria No More, one of Exxon’s collaborators in Cameroon. “They’ve been a great partner.”

Even when the foundation decided to pull out of Malaria No More projects in Tanzania and Senegal, they gave an 18-month warning, enough so that there was time to find replacement funding.

Climate change

ExxonMobil’s PPP in Cameroon has one issue that some other PPPs don’t: The company’s main business affects the environment in a way that some say exacerbates the problem its PPP is trying to remedy.

The mosquitoes that carry malaria breed in standing water. Some of the rivers and streams near ExxonMobil’s Cameroon pipeline were disrupted during its construction.

“Many years after construction, we still see some of the consequences in terms of standing water that we can see now which was not there before construction,” says Samuel Nguiffo, who heads the Center for Environment and Development in Cameroon.

“Part of the money paid by the company could be seen as a type of compensation to repair the additional rate of malaria in the area,” Nguiffo says, although he notes that his group has never been able to get before-and-after data from ExxonMobil, so he cannot be sure if malaria rates near the pipeline are higher now.

His other concern is more global, and more complicated.

“If you consider the volume of oil extracted by Exxon or some of the companies existing before Exxon but part of the same family in history, you can say the contribution of Exxon to global warming is very high,” he says.

The connection to malaria? According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), fossil fuel emissions are primarily responsible for increasing levels of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, which in turn leads to warming in some places, and an extension of habitat for mosquitoes.

The impact of climate change on malaria rates is layered, with increased risk in some areas and decreased risk in others, with no global count as yet. Climate change also promotes other infectious diseases, including Lyme disease and dengue fever, in some regions. There’s an irony for what ExxonMobil is doing, says Nguiffo, “knowing that global warming will lead to more diseases on the one hand” and then trying to use the money they earned by exacerbating the problem to do good. And climate change threatens health in other ways, by causing heat waves, by worsening air quality, and by spurring drought and extreme weather events, according to the IPCC.

ExxonMobil has a long history of pushing against the idea of climate change but Suzanne McCarron of the ExxonMobil Foundation says the company “takes the issue of climate change very, very seriously.” As for a malaria connection, she says, figuring out the impact on infectious diseases is best left to climate scientists. From the foundation’s viewpoint, she says, malaria is a very serious issue.

“I think the environmentalists and others would agree that it’s important that we are engaged in this activity,” she says. “We think we have a lot to bring, and we think can make a real difference.”

On the ground in Cameroon, health officials say they have bigger health worries than a connection between ExxonMobil and climate change.

“We prefer to target, to be specific” says Fondjo, the head of Cameroon’s malaria control program. “And our problem is malaria that kills.”

And even among environmentalists, no one is suggesting ExxonMobil get out of the malaria business.

“I don’t think they should stop giving the money,” says Rosenberg, of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

How much is enough?

The final question: Is ExxonMobil giving enough? A 2013 study by PSI and Devex — an organization of NGOs, private companies and funding agencies — identifies ExxonMobil as the largest private-sector funder in the fight against malaria. But veteran environmentalist Bill McKibben, cofounder of 350.org, says the $120 million spent so far “is about what ExxonMobil spends each day exploring for new hydrocarbons, even though the scientists tell us we already have four times more carbon in the global inventory than we can burn without triggering absolute disaster, including health disasters on a massive scale.”

Rosenberg says, “That’s their paper clip budget,” given ExxonMobil’s total 2013 earnings of $33 billion.

From the opposite end of the telescope, Paul Obam, in a tiny Cameroonian village, can save lives that would have otherwise been lost and give parents confidence that their children will live past the age of 5. And giving up now could have some disastrous consequences in the effort to eradicate malaria.

Olivia Ngou, country manager of Malaria No More, says people are finally beginning to absorb the idea that malaria can be stopped, a notion that her group has been promoting through public service announcements, public events, and other work her group has done through an ExxonMobil PPP.

“Now we’ve reached the stage where we’ve created a demand,” she says. “Now people are excited.”

The acting country representative of ACMS, Dr. Jean Christian Youmba, says someday he would like to let ExxonMobil off the hook.

“We must think how to bring the people to develop themselves, to take care of themselves,” he says. “I think this should be the long-term perspective."

More from GlobalPost: Coca-Cola's river cleanup work in Tanzania shows mixed motives