To cure Ebola, look at sepsis

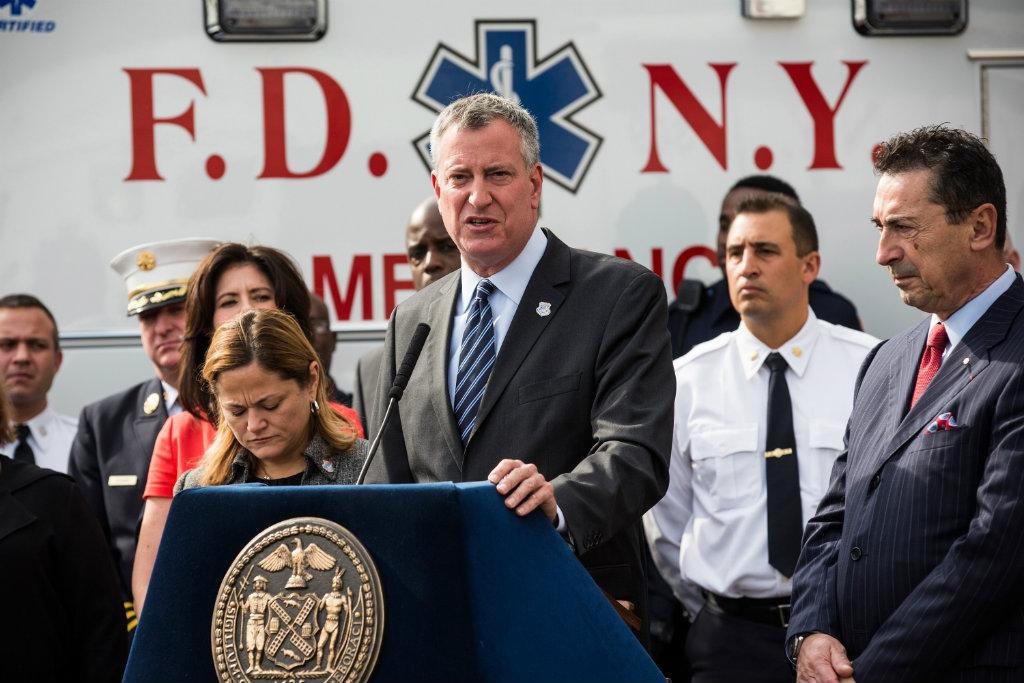

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio speaks at a press conference regarding the ongoing concerns of Ebola and the city’s efforts to contain the virus on Oct. 28, 2014 in New York City.

It’s now been a few months since the Ebola pandemic made front-page news, and in that time, it seems, our conversation about the disease grew far more nuanced.

We still care deeply about providing treatment to the afflicted—Time Magazine chose the doctors fighting Ebola as their persons of the year—but we approach the virus now with far less panic than we had before. That’s a good thing—good science requires thoughtful reasoning—but we’re still neglecting a major part of the Ebola puzzle. It’s as stark as it is shocking: no one dies from Ebola.

Instead, Ebola patients—just like those stricken with a host of other horrible and hard-to-cure diseases—die of sepsis, a complication that occurs when the chemicals released by the body into the bloodstream to fight infection end up themselves setting off a lethal inflammation.

Don’t get me wrong: the Ebola virus is still a terrible and deadly one, but if we successfully target the deadly sepsis caused by inflammation, we’ll save very many lives. And not just the lives of Ebola patients: each year, sepsis claims the lives of more than 225,000 Americans annually, making it one of our country’s deadliest conditions.

How, then, do we go ahead and fight this disease?

An important, if heart-breaking, place to start is to consider the story of Rory Staunton, a 12-year-boy from Queens, New York who developed sepsis following a fairly minor injury from playing basketball. Sepsis was not recognized early enough in his visits to the hospital, and when it was diagnosed, it was too late.

Much like Thomas Eric Duncan, the first patient in the United States to die from Ebola, Rory returned to the hospital after a few days, at which point there was little physicians could do to save his life.

His parents, Ciaran and Orlaith Staunton, led the fight to pass Rory’s Regulations in New York, which mandate, among other things, that a patient be kept in the hospital if he or she displays any of the warning signs of sepsis.

Several states have since adopted these regulations, and a recent meeting that I attended on Capitol Hill with Senator Charles Schumer, Representative Joseph Crowley, and Dr. Thomas Frieden, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, focused important attention on driving federal efforts to identify this as a threat to national health. There is evidence that these measures, applied across large health systems, save lives.

Deployment of major sepsis awareness protocols and rapid sepsis response teams within our hospital system, North Shore-LIJ, slashed the mortality rate from sepsis by 50 percent, equivalent to hundreds of New Yorkers annually.

Regional successes can be duplicated across the country. A major ally in combating sepsis is the Global Sepsis Alliance (GSA), an organization I co-founded in 2010 that now represents more than 1 million caregivers in 70 countries. The mission of the GSA is to provide a unified voice to those who treat sepsis, and to elevate public and governmental awareness.

A unified, global approach is absolutely necessary if we’re to stop a deadly, global pandemic. And a pandemic it is: Sepsis is currently one of the biggest killers of adults and children worldwide.

Awareness of Ebola is high, in contrast to sepsis, and an important time has arrived to focus attention on the science and prevention of sepsis as a more serious global threat. Deaths from sepsis, whether initiated from Ebola or other more common causes, require a galvanized effort to be curbed.

The impact of such efforts will surpass the inevitable success that will come from the international fight against Ebola, which will undoubtedly lead to new vaccines and therapies. It’s an uphill battle, but we have no other option but to apply similar mandates in place for sepsis to our fight against today’s headline disease.

Dr. Kevin Tracey is a neurosurgeon and president and CEO of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research at North Shore-LIJ Health System.

More from GlobalPost: Some people would rather die of Ebola than stop hugging sick loved ones

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!