This crazy Ukrainian election shows the country has a ways to go toward reform

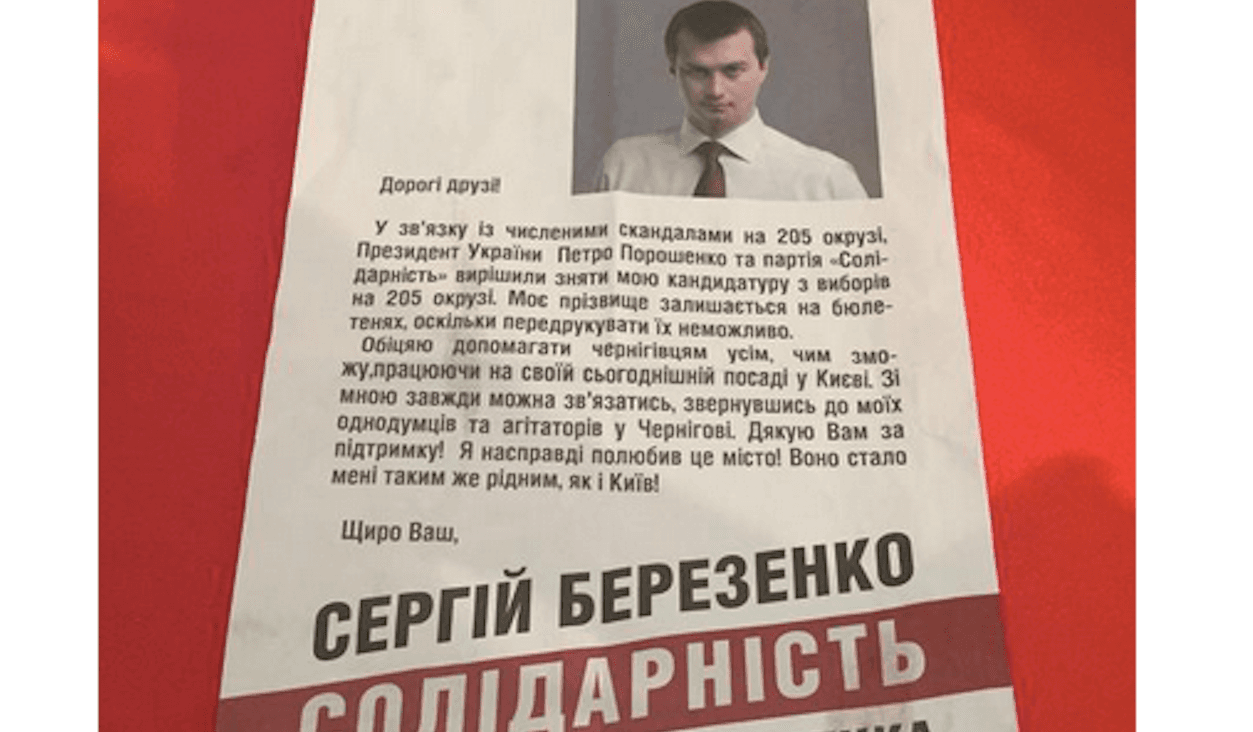

One fake campaign flyer announced a leading candidate was dropping out of the race.

CHERNIHIV, Ukraine — The old and infirm crammed, cursed and complained as they fought for spots in line on Saturday under the oppressive afternoon sun.

On offer at a local park were goody bags of pantry items — things like sunflower oil and sugar — courtesy of a well-connected millionaire eager to cast himself as a man of the people.

That man, Hennadiy Korban, just happened to be running for a vacant seat in parliament the next day to represent a district in this charming, provincial city north of Kyiv.

And what his team considered an act of goodwill most others saw as something different: bribing poor, unwitting voters.

Want to win an election in #Ukraine? Hand out free food and goods.

A video posted by Dan Peleschuk (@dpeleschuk) on

The scene was one of many peculiar images to emerge from this city of around 290,000 in recent weeks as it prepared for a special election that captured the national media’s attention.

The top two candidates for legislator were accused of employing an array of dirty tactics — from simple mudslinging to outright vote-buying — in a campaign that observers believe undermined Ukraine’s trundle toward cleaner democracy.

“Many people are talking about the fact that the elections for district 205 in Chernihiv are a very big step backward,” said Pavlo Pushchenko, the local head of a national vote-monitoring NGO.

By Monday afternoon, the election had come and gone, with early results giving Serhiy Berezenko, the other top candidate, a hefty lead over Korban.

Vote monitors and local police said they registered dozens of violations on Sunday, such as attempts at multiple voting.

It was an undramatic climax to a campaign full of crooked political technology, as it’s known in this part of the world.

Both leading candidates were juiced in: Berezenko is a close ally of President Petro Poroshenko, while Korban is the right-hand man to one of Ukraine’s richest and most powerful oligarchs.

Neither of them were even from the region, using electoral district 205 simply as a springboard into parliament.

Sunday’s vote was seen as a high-stakes proxy battle between Poroshenko and a very rich man, Ihor Kolomoisky, who has publicly challenged the president and remains his top political rival.

That’s partly why the vote, a contest between political muscle and big money, was so important to win.

Korban’s campaign was marked mostly by public handouts to cajole voters — known in slang here as “buckwheat” — and staging lavish concerts near his sleek campaign headquarters.

But he also took an active role in engaging his competition. A week before the election, his security detail captured a car, allegedly belonging to Berezenko’s team, stocked with ammunition and cash. Korban claimed it was used to pay off voters.

Berezenko, meanwhile, made full use of his ties to the president’s political machine, plastering the city with its party colors. He was even given a position on a brand new government advisory body for regional development. That gave him de-facto local authority — and access to purse strings — before the campaign even began.

Experts believe the goal was to reassert the presidential party’s authority in Ukraine, especially before nationwide local elections later this year.

“The president’s team cannot lose,” said Volodymyr Fesenko, a political analyst in Kyiv.

In the days before the vote, there were reports of hired thugs from both sides roaming the city to stir trouble. Fake campaign leaflets, like one announcing Berezenko was dropping out of the race, made their way around town.

On election day itself, voters had to choose from an astounding 91 candidates, most of them spoilers, analysts said, designed to draw votes away from the front-runners.

A particularly popular tactic is to register candidates with similar last names to confuse voters — hence “Karban” and “Korpan” on the ballot.

Both leading candidates regularly denied any suggestions of wrongdoing, each accusing the other of political manipulation.

But critics say they’re actually both guilty of tarnishing the values of the so-called “Revolution of Dignity,” which many Ukrainians expected would overhaul the country’s corrupt politics.

Ihor Andriychenko, a local politician from a liberal grassroots party who came in fourth, called the election “a farce, a political theater of absurdity.”

“They were supposed to demonstrate real, transparent elections: a battle of ideas, competition, debates, intellect — anything else,” he told GlobalPost before the vote. “But definitely not ‘buckwheat,’ and definitely not money.”

Many locals, meanwhile, appeared either too uninterested or exhausted with the campaign to come out to vote. There was a 35 percent turnout, and city streets were noticeably empty.

Some voters even resorted to the classic post-Soviet tactic of marking up their ballots with obscene or irreverent messages.

Back at the free food line on the eve of the election, an exasperated pensioner who identified herself as Maria grew visibly upset as she watched her mostly weak and destitute neighbors gather near the handout station. It was emblazoned with Korban’s party logo.

“We’ve fallen so low that we’ll sell ourselves for a kilogram of buckwheat,” she said, adding that she had little faith in either candidate.

“Korban, Berezenko — neither of them will do anything nice for us.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!