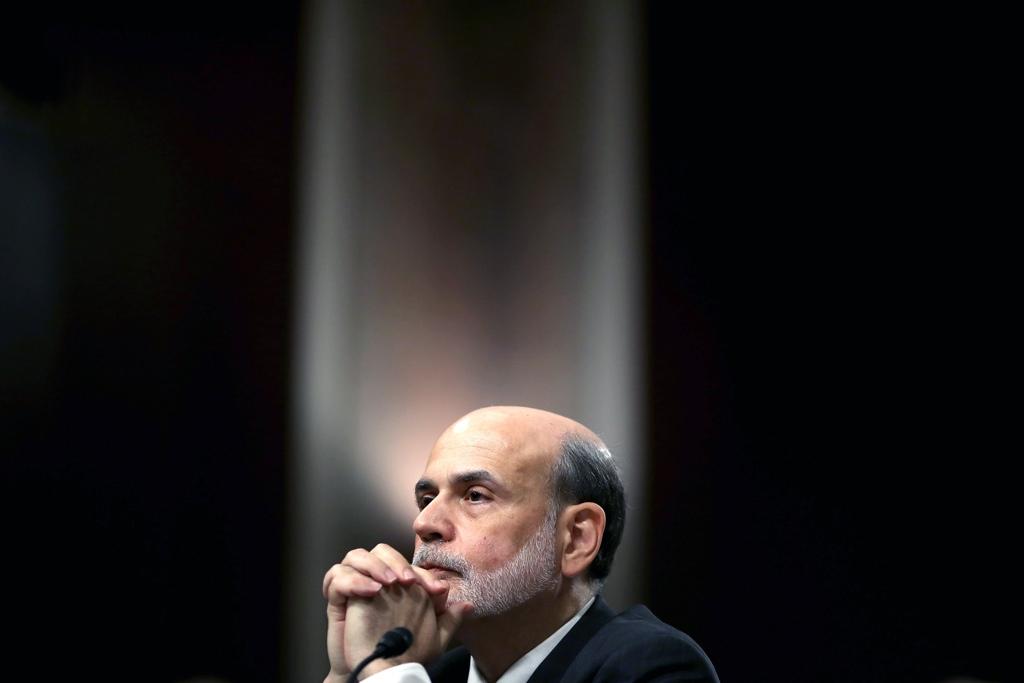

Big Ben’s shadow

Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke.

NEW YORK — The most powerful man on Earth?

Sorry, Mr. Putin, it certainly is not you, though you do a damned good Darth Vader impersonation. And Mr. Xi, China may make a good platform someday for world domination, but there’s really no question now. One refurbished 1970s former Soviet jump jet carrier does not a juggernaut make.

Nor is it John Kerry, Barack Obama or any of the US military’s “component commanders.” None can hold a candle to the true titan: short, balding Ben Bernanke.

It may be no exaggeration to say that the most important foreign policy decision of the still young century will be made in the next year by the US Federal Reserve chairman, as he begins to dial back the faucet of low-interest dollars his bank has sprayed across the world since the 2008 financial crisis.

Since roughly the start of the summer, the engine driving the global economy has kicked into reverse. Most of the planet’s growth suddenly appears to be happening in the developed world rather than the emerging markets (EM).

Since January, the top 10 EM stock exchanges are in negative territory, some of them deeply. The economies of all the BRICS — Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — are underperforming, and there’s talk of real crisis in a few (though it’s overdone in China’s case — see my last column).

“QE,” as the Fed’s global crop-dusting of dollars is best known, is short for quantitative easing. It’s when a central bank buys up assets, such as government or corporate bonds, to increase an economy’s money supply. The Fed’s been using this tool to flood America’s financial circulatory system with the life’s blood of cash after its reckless banks pushed it into cardiac arrest.

Instead, QE flooded the world with cash. American and other banks parked their free money in high interest rate foreign markets, stoking inflation in some of the more open ones (Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, for instance) and pumping up mini-asset bubbles of various kinds in them all, from commodities to real estate to credit. Even Russia looked good for a while.

Suddenly, with barely a whisper of the word “tapering” from Big Ben, a low-level panic has set in. With the Fed talking about an end to QE sometime next year, the likelihood is that all those dollars that were parked in high-interest EM accounts to make an easy buck — what bankers call “the carry trade” — will fly home to America and its recovering corporate, real estate, energy, equities and other markets. Talk of a coming boom in US stocks is rampant (and reflected in the 19 percent spike in Japan’s Nikkei Index in the past six months and a 7 percent rise in the Dow Jones Industrial Average).

Over the past week, as fears of QE tapering have begun to spiral, economies large and small have been manning the defenses.

• Brazil, already stuck with 6.5 percent annual inflation, announced a $60 billion stimulus aimed at halting the slide of its currency’s value against the dollar.

• Indonesia announced what amount to penalties against imported luxury goods.

• Turkey’s Central Bank auctioned off dollar assets in an effort to stop its currency, the lira, from falling.

• India, like all four, has tightened “capital controls” to prevent a flight of dollars it holds out of the country.

How did Ben Bernanke, a financial academic from South Carolina, wind up holding the fate of much of the planet in his hands?

It began with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) at the end of the George W. Bush administration, authorizing the federal government to buy up the “toxic assets” piled up by dopey banks during the housing bubble. That was meant to prevent the American banking industry from collapsing, and in that sense it worked. But in the years that followed, the Federal Reserve supersized it, continuing to buy toxic securities and issuing US Treasury bonds that have been the world’s overwhelming choice as a safe haven in volatile times.

Since 2007, the Fed’s rounds of QE have added over $2.6 trillion in “new money” to the global economy (as well as to its own balance sheet).

All this, rather stunningly, has failed to stoke inflation or cause the US government’s own borrowing rate to rise — the two fears trumpeted by the right since the start. The economy’s seeming immunity to QE is the vast, unappreciated benefit of the US dollar being the “global reserve currency,” and the country’s (so far) spotless record for honoring its debts, Tea Party brinkmanship and drunken sailor pork barrel spending aside.

Put simply, the world still needs our money, whatever they may think about Iraq, Justin Bieber or the NSA.

The degree to which all this QE helped the US economy is debated. Certainly, it staved off the collapse of the reckless banking giants that precipitated the crisis. But it hardly stoked the economic engine: at best, it prevented the worst; at worst, it’s gone on too long, cheapening the US dollar. (Follow the debate via doomsayers on the right like Peter Schiff and QE cheerleaders on the left like Paul Krugman, but I like this short piece as a balanced primer on the debate).

But if QE and its results in America’s economy remain the stuff of furious left-right debate, its real effects for years have been overseas.

Because, due to a lack of courage and foresight when the TARP bailout was designed in 2008, the US banks that the Fed created all this new money to save decided not to pump it back into the US economy. (Some simple incentives added to the TARP bailout could have ensured this happened, but that was asking the Bush administration’s investment banker Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson to go one step too far).

Instead, for over five years now, the banks have taken all the money the Fed has loaned to them at virtually no interest as part of the “easy money” policy and have immediately parked that money overseas in high-interest rate economies like Brazil, Indonesia and Turkey. Without lifting a finger, they make 5 to 10 percent profit on the rate difference.

That game, at least in the form that benefited and pumped up emerging-market numbers, is now over. The new money the Fed threw after bad will now come home to roost, one hopes, in the US economy at last. For those who lost houses, jobs or a chance at higher education in the meanwhile, the return may be bittersweet. But better late than never.

Michael Moran, foreign affairs columnist for GlobalPost, is also vice president, global risk analysis for Control Risks, an international political, integrity and security risk consultancy. He is author of The Reckoning: Debt, Democracy and the Future of American Power.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!