Back to school in Sudan’s war-torn Nuba Mountains

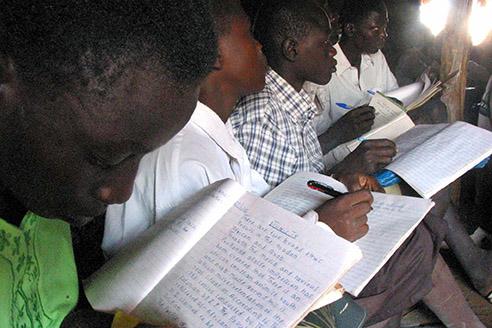

Primary school pupils in Kaudi, central Sudan's Nuba Mountains region, Nov. 28, 2003.

KAUDA, Sudan — Dozens of waist-deep holes are dug around the perimeter of this primary school in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains.

At first, they look like graves — but they were actually excavated to keep people from death. They are rough bomb shelters, built to shield teachers and students from the Sudanese government's punishing air raids.

“When they hear the plane, [the children] hide themselves in the holes,” said Patrick Alalo, the principal of St. Vincent Ferrer primary school in Kauda. The school hosts some 440 students in just 10 classrooms.

It’s a harsh reality for primary school kids living under the constant threat of war. A decades-old conflict between mostly black African, Christian rebels and an Arab, Islamic regime in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum, has reignited in recent years.

As the most recent bout of fighting enters its third year, and the Sudanese government in Khartoum continues to ban humanitarian organizations from the region, people here are trying to impose a kind of normalcy on their violently interrupted lives. One aspect of that is education.

More from GlobalPost: Nuba Mountains: Sudan's next Darfur?

“Everybody is afraid to send their children to school or to come together anywhere because of the planes,” Alalo, the principal, said. “Education is so important — without it, we are useless.”

The government in Khartoum has for decades withheld education and other basic state services from the country's largely black African south — a move critics and human rights groups say is a bid to marginalize the local population.

As a result, South Sudan — which seceded from Sudan in 2011, and borders the Nuba Mountains — has some of the world’s lowest literacy rates. The Nuba Mountains fare no better.

According to figures compiled by the Nuba Relief, Rehabilitation and Development Organisation (NRRDO), a local civil society group, there are currently around 36,300 pupils enrolled at 141 primary schools across five rebel-controlled counties in South Kordofan state, where the Nuba Mountains are located.

Although no reliable census has been conducted in years, NRRDO says the population of these counties could be as high as 1 million, meaning school enrollment rates are woefully low. Prospects for those who attend primary school remain poor.

When fighting resumed here in mid-2011, close to 100 schools, including the only two secondary schools in the region, were forced to shut down as pupils and teachers fled.

The most qualified schoolteachers were expatriates, mostly from Kenya and Uganda. They left when the bombs began to fall and few have dared return. The children, too, left school out of fear, preferring instead to stay close to their homes in the protective rocky hills. At least 20,000 pupils stopped attending school.

But as the war grinds on, locals have revived efforts to restore even the most basic of education services.

Educators here say reopening schools is a way to address the physical disruption caused by the war.

Today, at St. Vincent's in Kauda, pupils scurry between tin-roofed classrooms in light blue and beige uniforms, clutching their rudimentary textbooks.

Kenyan, Ugandan, and Sudanese teachers — some of whom have returned — write on blackboards or mark homework in the staff room.

The Catholic Diocese of El Obeid, which funds the school and others in the area, plans to open a new secondary school next year. Recently, a small teacher-training college was also opened.

The college is "the future nucleus of education in the Nuba Mountains," said Bishop Macram Max Gassis, the head of the diocese now exiled to Kenya.

He hopes it will remove the need to import teachers from abroad, permit the Nuba people a measure of self-sufficiency, and ensure schooling continues and spreads.

For now, daily survival is what is on the minds of most students here.

"The Antonovs [aircraft] scare us," said 19-year-old Shadia Adlina. The conflict's disruption of the area's education system means most of the students here are much older than would be typical.

Alalo, the principal, converted the school's storeroom into a classroom for secondary school pupils.

"We can’t concentrate on our studies," Adlina said, adding that the last air raid took place just a few days earlier, in May, dropping bombs on Kauda's market.

In the late afternoon, as the sun slips behind a distant ridge of hills, pupils outside play volleyball.

It’s like any other schoolyard scene, until a mishit sends the ball bouncing into one of the nearby foxholes.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!