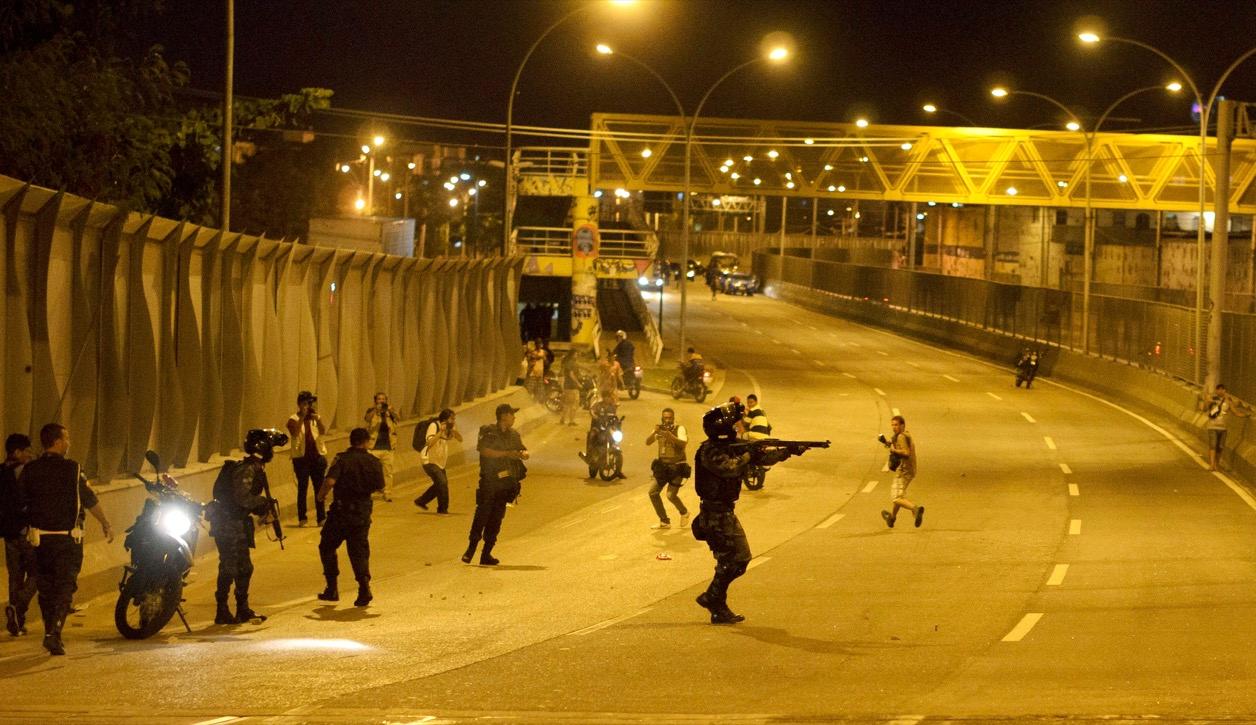

Policemen take positions during a shooting with suspected drug gangs on Linha Amarela highway near the Maré favela complex in Rio de Janeiro on Feb. 23, 2015.

Residents of Rio de Janeiro’s Maré complex of poor favela neighborhoods were too terrified to walk down the street.

Nighttime police raids and daytime shootouts between police and a drug gang last week killed three civilians, wounded two officers and kept people shut inside a classroom for hours while bullets whizzed outside.

Officials said the dragnet was part of efforts to arrest an escaped drug trafficker. But Maré activist and university engineering student Carlos Gonçalves says “conducting the operation in that way was not necessary in order to make the arrest. That’s a choice the police make to cause terror in the community.”

‘More than 55 on- and off-duty officers have been killed in the state of Rio so far this year.’

After civil society groups denounced the police raids, a judge barred officers from searching homes in the middle of the night, based on a constitutional right that prohibits “violations of the home.”

“It’s a tiny step forward that shows it’s possible to demand the government respect our rights,” says Gonçalves, 25, who studies at State University of Rio de Janeiro.

Activists have made demands like that for years, but say that online social networks and new smartphone apps are helping power up their demands.

The latest app is Fogo Cruzado — Portuguese for “crossfire” — designed by Amnesty International Brazil. Gonçalves downloaded it right when it launched Wednesday.

There have been more than 570 gun fights in the Rio metropolitan area so far this year, according to the app's data director, Cecília Olliveira. She based her tally on reports from local media and online social networks. These include conflicts among the city’s three drug factions, extortion gangs run by former and off-duty police officers called milícias, and the police themselves. They add up to make Rio one of the most murderous Olympic cities ever; with 18.5 killings per 100,000 inhabitants in 2015, according to government data.

In the state of Rio, police were responsible for one in five killings last year, says Human Rights Watch.

This was supposed to be Rio’s hour to show off police reform. As part of preparing for the Olympics, in 2008 the authorities launched a “pacification” program in poor neighborhoods aimed at reducing violent crime through community policing tactics. After positive starts in some areas, the program has faced serious problems.

Read more: Before the Olympics, gang violence surges in Rio’s poor neighborhoods

One of its biggest challenges, according to retired police Colonel Robson Rodrigues, is the pressure from tough-on-crime politicians and police who don’t believe community policing or prevention-based strategies work.

Rodrigues directed the pacification program for a year, helping implement a tracking program for police killings and number of bullets fired for districts across the state. “We were able to reduce homicides at the end of 2015 in small districts that received special resources, training and monitoring,” he says. But politicians who support the logic of shoot first, ask questions later remain influential. “They won’t make those arguments in an academic or open forum, because they don’t have the numbers to back it up,” Rodrigues says.

Apps like Fogo Cruzado are designed to put data not just in the hands of the authorities but also the people, who can increase political pressure, says Rio Amnesty campaign coordinator Rebeca Lerer.

Shootouts in Rio are not officially tracked. And the violence figures that are published are hard to read for non-specialists. In 2016 so far, government data indicates that killings by police in the first five months have risen to 322, from 305 during the same period last year. Fogo Cruzado aims to add context about which neighborhoods suffer those shootouts and what other damage occurs.

“In Rio there is often media and public outrage when someone is killed in the city’s wealthy South Zone, whereas constant shootouts, killings, and school and hospital closings are normalized for residents of the city’s favelas, where the population is majority working class and black,” Lerer says.

Despite reform efforts, “the logic of the war on drugs and military control of poor neighborhoods continues,” she says, adding that weekly and monthly reports from Amnesty’s new app will provide an “X-ray of which populations pay the biggest price.”

Brazilian police also get killed. So far this year, more than 55 on- and off-duty officers have been killed in the state of Rio, according to journalist Roberta Trindade. “The majority of Rio police caught up in this cycle too are working class and black,” says Rodrigues.

Amnesty’s app joins other tools launched recently to track public safety issues. The mobilization network Meu Rio manages a WhatsApp hotline called Defezap for private video uploads on anything from a complaint of abuse by a subway guard to a police officer reporting a superior’s misconduct.

And favela youth rights group Fórum de Juventudes, of which Gonçalves is a member, created an app called Nós por Nós (“Us, by us”) that collects reports and spells out legal guidelines for stop and frisk, detentions, and the right to speak freely, film, and identify officers.

Gonçalves says these technologies are especially crucial at a time when he suspects his favela complex, Maré, may soon be occupied by the army in a pre-Olympics measure. A 15-month military occupation that began before the 2014 soccer World Cup cost around $200 million and led to reports of abuse. “These apps could help register details like the fact that during the last occupation, the army conducted dangerous operations when children were going and coming from school,” Gonçalves says.

Brazilian Justice Minister Alexandre de Moraes told reporters on Wednesday “we are doing all necessary tracking, all the intelligence gathering, to give peace to Brazilians and foreigners coming to the Olympics.” Defense Minister Raul Jungmann said the presence of 21,000 federal troops would supplement local police actions.

On Wednesday, the day after the troops started patrolling Olympic venues, Amnesty’s “crossfire” app received almost 100 reports of shootouts throughout the city in its first 24 hours of operation. Data director Olliveira cross-referenced these with other reports and recorded gun fights in the favelas of Complexo do Alemão, Acari and Rola, where one policeman was killed. Police themselves, who have threatened strikes over late pay, are among the Rio residents tracking violence with the app, Olliveira said.

Raull Santiago, 27, is a member of independent journalism group Papo Reto in the Alemão favela complex. He hopes to use data from new technologies not only to clarify which communities face the heaviest cost for public security strategies, but also to push for drug policy reform. “What happens in the war on drugs,” says Santiago, “is the rich get the drugs and the poor get the war.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!