Thailand’s top female monk hacked the system to bring women into the fold

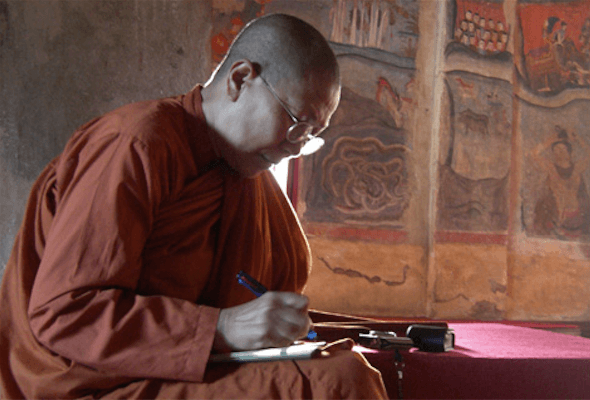

Dhammananda.

Dhammananda, a 72-year-old Thai woman, is forbidden from hugging her sons. She’s never been able to chase her giggling grandchildren around the room. Both acts are forbidden by the strict Buddhist precepts that monks must follow.

Dhammananda is a self-described “rare species.” She’s a monk. She’s also a mom. And in the eyes of her homeland’s Buddhist establishment, she’s a feminist insurgent.

Each day, she and her female disciples wear the same clothing: flowing robes the color of ripe mangoes. Their heads are shorn down to stubble. Their possessions are limited to flip flops and little else.

In other words, their day-to-day lives are largely indistinguishable from that of any upstanding Buddhist monk in their native Thailand.

But because they are women, Dhammananda and her flock of 15 female monks are shunned by the state-backed Buddhist hierarchy. This powerful all-male order, known as the “sangha,” regards them as imposters.

“That’s their problem,” Dhammananda says. She’s the abbess (yes, that’s female for “abbott”) of a temple 60 kilometers west of Bangkok.

“That’s their own ignorance, which they’ll have to overcome.”

There are roughly 300,000 monks in Thailand, home to one of the highest concentrations of Buddhists on the planet. Yet only 100 are women. They’re scattered among small temples that the traditional order views as insolent.

Before Dhammananda, there were none at all. Prohibited from ordination in Thailand, she hacked the system in 2001 by flying to Sri Lanka, which started ordaining women in the mid-1990s.

She then returned home as Thailand’s first female monk in modern times — at least in the old-school Theravada strain of Buddhism that dominates Southeast Asia.

In Dhammananda’s view, the near absence of women in the monkhood has left Buddhism as wobbly as a three-legged chair. The faith is lopsided, she says, because it lacks feminine insight.

Past experience as a mother, she says, is particularly valuable to Buddhist spiritual life. “That experience makes you whole,” she says. “You tend to understand people’s problems on a different level than men do.”

The argument against allowing women into the monkhood is shaky, she says. Roughly 2,600 years ago, Buddha explicitly stated that women can achieve enlightenment. He even ordained his own foster mom.

“Enlightenment is the quality of mind that goes beyond. There is no gender there,” Dhammananda says. “When you talk about the supreme spiritual goal in Buddhism, it’s genderless.”

Thailand’s monastic order, however, rests its case against female monks on a technicality. The sangha insists that female monks can only be brought into the fold by other women.

But because the sangha in Thailand has never sanctioned a female monk, there are no women available to open the door to newcomers. The original lineage of female monks dating back to Buddha’s time faded out centuries ago.

Thailand’s official Buddhist order “feels women are a big threat. Especially women in robes,” says Sulak Sivaraksa, one of Thailand’s best-known Buddhist scholars.

“But since [the female monks] are wonderful people, more and more people recognize them,” Sulak says. “I told the Thai [female monks] … to keep clear of scandal. Do good work. And soon the male monks will not only recognize you. They will come and worship you. They will be led by you.”

Like any Buddhist monk, female monks such as Dhammananda are sworn to a dry life that forsakes romance, luxury and excess of any kind.

Holding hands? Devouring an entire carton of Häagen-Dazs in one sitting? Pop music or even gossiping? All are forbidden. More than 300 rules (called precepts) dictate their behavior to ensure they do not grow attached to sensual pleasures.

Nor can they work. They acquire nourishment by walking the streets and collecting free food — often soy milk, rice or curry — from everyday Buddhists.

Here are Dhammananda’s thoughts on rebellion, moms in the monkhood, and the decadent treats she misses from her life before the temple. Her comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Do you think of yourself as a rebel?

I never thought of myself as a rebel. Even though I might be one.

My intention is not to provoke. My intention is to insist that we return to the right path.

Would you call yourself a feminist?

Yes. Not that I ever studied feminism. But my understanding of feminism is you should bring out your potentiality to the fullest. Anything obstructing your path, you should work against it. That’s my feminist attitude.

When your sons come to visit, are you allowed to hug them?

No. That is a very hard part. Particularly for my oldest son. He really misses that. He once said to the [other female monks], “You don’t know how much I miss my mother.”

He’s kind of making an offering to the Buddha by giving up his own mother to do this job. But he still misses the hugs.

Are there special rules for men speaking to female monks?

As long as there is a third person around, and as long as we are not sharing the same seat, [men and female monks] can be close. But I must have a sister [fellow female monk] here as a witness.

You have very young grandkids. What are the rules regarding grandchildren? Can you pick them up and play with them?

The youngest is a boy and, yes, I have held him. I don’t think of him as a man so I’m not touching a man. He’s a two-year-old boy. A child! But I don’t go around hugging him.

As I understand it, monks aren't even allowed to tickle?

Oh yes! You aren’t supposed to tickle a monk. Because people will roll into a great laughter. That’s part of the rules.

So no tickling your grandchildren?

No, that rule is about tickling monks. Not about tickling laypeople. But, no, I don’t tickle them.

How do regular people treat female monks out in public?

There are two groups. Some couldn’t care less. Others are more suspicious. But for those who are interested, we educate them. It’s much easier now compared to 16 years ago when I was the only female monk walking in this land.

Tell me about your first day collecting alms.

I was invited to Rayong (a Thai coastal province) for a seminar. And I went out with the male monks. People in the marketplace, when they realized the last one walking in the back was actually female, they were so interested!

One household ran inside and grabbed a big box of drinks and offered it to my [alms] bowl. I was happy.

To go back to Buddha’s time, it’s said that if you make an offering to monks, that’s well and good. But if you make offerings to both monks and female monks? It’s even better. This is in the text.

The ordination process for female monks involves embarassing questions, even sexual questions. Does that create more resistance to ordaining women.

For men, they ask, “Are you a man? Do you have such and such illness?” For women, they will ask about our private parts. “Do you menstruate all the time?” Or whether you have all of your sex organs.

But if I am willing to answer this, they should give us ordination. I think Thai women, young and old, are willing to go through this interrogation.

What do you miss about regular life?

I miss high tea. This here [gestures toward an 11 a.m. lunch spread donated by the local village] is our last meal of the day. So no high tea. I actually used to enjoy it more than dinner. Especially if it came with blueberry cheesecake.

Can't you just eat cheesecake in the morning?

It doesn’t feel the same way in the morning! You just have to give it up.

Some people who've been through challenges in life end up being pretty funny. Do you have a sense of humor?

I have a great sense of humor! The monastic life is quite dry. You need to laugh once in awhile.

You shouldn’t be making jokes all the time like a joker. But if you can show people another way to look at things, even by making them laugh, that’s OK.

People see monks and wonder: Does it really make you happy to give up everything like that?

Yes. Because we give up the bad things, not everything. It is letting go of that which is unwholesome.

But you have to let go of pizza. And high tea, as you mentioned. Or your boyfriend or girlfriend. It seems hard.

At certain points, it may be so. But then you look ahead in time, outside this context, and realize the goal is much greater than your boyfriend or your girlfriend. And much greater than pizza.

What sorts of backgrounds do the female monks here have?

All different backgrounds. This one studied journalism. The next one over was a seamstress. Some were just ordinary factory workers. Two of them have master’s degrees.

If there was a vote, do you think Thai society would allow women to be ordained?

Ordination is our heritage given by the Buddha. So we should not be ordained expecting people to accept me. You should ordain because you want to do it and to keep our heritage alive.

As a monk you have to subdue your anger. But doesn't it make you irritated that people think you shouldn't be a monk?

I cannot put the ignorance of all the people in the whole world on my shoulders.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!