The geography of Brexit: What the vote reveals about the Disunited Kingdom

A workers counts ballots after polling stations closed in the Referendum on the European Union in Islington, London.

A majority in the UK voted to leave the European Union. But a look at the geography of the vote provides another angle on the result and insights into the political landscape of the Disunited Kingdom.

The vote laid bare a seldom-acknowledged political and economic imbalance within the country. It has also raised the chances of dissolving a more than three centuries-old union.

Regional inequality

The very first result of the referendum came from Gibraltar, the giant, British-owned rock that juts out from southern Spain, home to 32,000. It was not a useful predictor of events to unfold as close to 96 percent of the votes cast were to stay with the EU. The reason: The EU assures that Gibraltar remains British and deflects Spanish claims. With the UK outside of the EU, Spain can press home their claim. Spain has already asserted the right to some form of joint control over the rock.

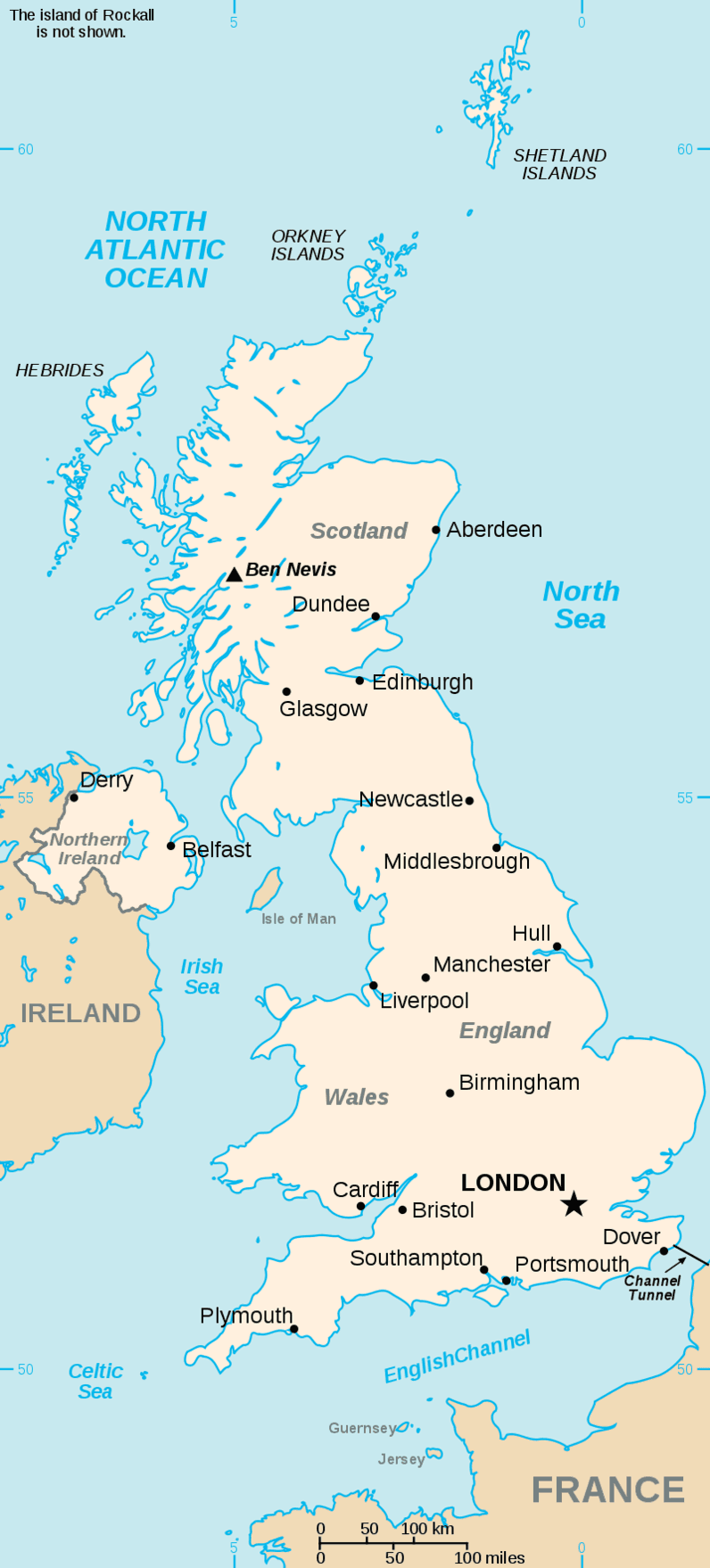

A major area of support for remaining in the EU was centered in London. So-called Greater London comprises 7.5 million people and the greater metropolitan region has a population of approximately 21 million. The reach of the city extends into most of the southeast part of the country and beyond.

The city and its extended metropolitan dominate the nation. The wealthy, the influential, the movers and shakers live in the city; it is home to royalty, the political elites, those who control much of the making and moving of money. It is by far the most affluent part of Britain. London has emerged a global financial center attracting expertise and investment from across the globe and around Europe. London is hard-wired into the financial circuits of the EU and global economy.

There is a spatial dimension to this social inequality. The UK has the most marked regional inequality in Europe. The rich and wealthy are concentrated in London and the southeast, where household incomes are higher than the rest of the country. As the UK became a more unequal and divided society, the cleavage between London and the southeast compared to the rest of the country is becoming more marked.

Now let’s look at the rest of England and Wales, where the majority voted to leave. The people in these regions, especially the lower income groups, were bypassed by the emphasis on the London money machine. Spatially, class conflict was often framed as the southeast versus the rest of the country, although in reality the divisions were as much social and spatial.

But even though there existed this discontent with the southeast power center in Wales and other parts of England, it was never strong enough to lead to demands for political separation as it could in Scotland. There was no constitutional basis and so the rest of of England and Wales seethed at the rising inequality and neglect.

The exit vote was prompted by many things, especially a disquiet at immigration, but it was also a vote against the dominance of London and the political establishment. The exit vote managed to capture popular resentment against the status quo just as candidates Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have in the United States.

Divergent interests

All districts in Scotland voted to remain in the EU. This is a complete reversal to the 1975 referendum when Scotland voted against joining the EU, when much of the rest of the country embraced the European project.

What happened? The EU provided benefits to Scotland that the London-biased UK government did not. Scotland’s political culture, it turns out, is closer to the EU than that of London-based Tories. And years of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's punishing rule in the 1980s soured many in Scotland against a reliance on the UK political system. The EU softened the neoliberalism of English Tory rule.

The Brexit vote highlights the problem of sharing a political space with divergent interests. Scotland's Parliament in Edinburgh will now move to draft legislation for another referendum on Scottish independence from the UK. The result could be different from the one in 2014, when 55 percent voted to stay in. The Brexit vote may herald the breakup of a union of states first crafted in 1707.

Northern Ireland, as a whole, also voted to remain in the EU. But the Anglo Welsh vote across the water that tipped the balance in the opposite direction raises new issues for the province. Northern Ireland, the only part of the UK that has a land border with an EU country, is in a similar economic position to Scotland but in a very different political context. The province is split between those who want to join up with Eire and those who want to stay in the UK. The Sinn Féin party has already proposed a vote to unify Ireland.

The future

The geography of the Brexit vote tells us much about the political geography of the UK. But what about the political future of the UK?

The Brexit vote reveals and embodies the deep divide in the UK between the different regions of England and Wales, and especially between the affluent London and the southeast. This division is unlikely to heal soon.

The different voting patterns between Scotland, Wales and England outside of the southeast may herald the breakup of the UK. The United Kingdom was always something of a misnomer. It is not a kingdom — the head of state currently is a queen — and it is not all that united. The Brexit vote is likely to exacerbate the breakup of Britain.

John Rennie Short, professor, School of Public Policy, University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

![]()