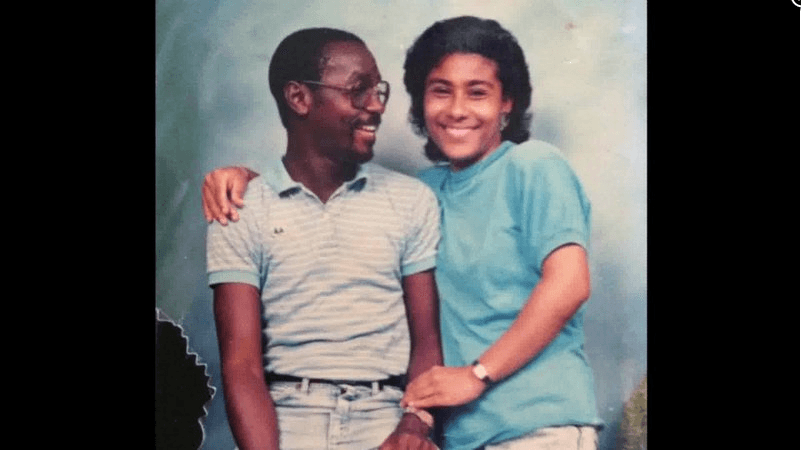

Montana is one of two states that does not have an office to accept refugees. But that's about to change, and Wilmot Collins wants his new neighbors to know that they can make a life here. He spoke about his journey from Liberia at a meeting on April 22, 2016. His son, Bliss, sits at the table.

When Wilmot Collins and his wife Maddie arrived in Ghana after escaping the Liberian civil war in September 1990, he weighed just 90 pounds. Maddie was about 87 pounds. They were starving, dehydrated and sick. Both had to be rushed to the hospital.

Four years later, they arrived in Helena, Montana, where they were resettled as refugees. Now Wilmot Collins, 52, works for the Department of Health and Human Services. Maddie Collins is a registered nurse. They own their own home. Their 24-year-old daughter is in the Navy while their 20-year-old son, formerly a high school football star, is a sophomore at the University of Montana.

Collins wants people to hear his story because he wants them to know that new refugees have something to offer.

And new refugees are coming: Montana is one of two states without a refugee resettlement office, but the International Rescue Committee will open an office in Missoula this summer. (The other state is Wyoming.) The last time the IRC had an office in Montana was 25 years ago; it closed in 1991 after a push to resettle Hmong refugees fleeing Vietnam was completed.

With the Obama administration under a tight deadline to hit its goal of resettling 10,000 Syrian refugees before the end of the year, there is a good chance some Syrian families may be among the first 25 or so refugees headed to Missoula.

Read the first story in this series: They were on opposite sides of protests about bringing refugees to Montana — but now they've formed an unlikely bond

Collins wants these new arrivals to know that, whatever initial difficulties they encounter, the state is a fundamentally a welcoming place.

“I will tell them that you have to have thick skin. There will be people that will say things that aren’t true about you,” he says. “But there are more decent people in this state than there are bigots. There are more decent people in this state than there are racists.”

Collins has encountered both sides of that coin. When he first arrived to Montana in 1994, the community had already rallied around his wife, who arrived more than two years earlier. He got off the plane to find a welcoming party put together by students at Helena High School and members of The First Lutheran Church. They held sheets of paper that together spelled out “Welcome home Wilmot."

“We got to the airport, man, it was like a foreign dignitary visiting Montana. And I’m like, all this for me? This refugee from Liberia?”

Eight weeks later, he got a call from a neighbor with news he didn’t expect. Word had gotten around town about the new refugee from Africa — and not everyone was so welcoming. His neighbor told him that someone tried to set his car on fire and wrote in black letters, “Go back to Africa" and “KKK” on the white siding of his home.

Collins was shocked and his wife was worried. He called the police and met them at their home. But by the time they got there to survey the damage, the neighbors had already started washing it off.

“When I saw that, I was shocked because I had never experienced that before and I didn’t know what to make of it. But when I started processing what went on, I said, ‘Wow, the outcome is good. My neighbors are good people.’”

“I think the people of Montana are very accepting and welcoming,” Collins says, reflecting on the incident. “But the problems we have is that without information, we tend to stick to what we hear. That is, if we do not educate the public on what refugees are about, they will stick to whatever bigotry they hear.”

“That’s why they tried burning my car,” he says. “That’s why the marked my home ‘KKK,’ ‘Go back to Africa’ — because they didn’t know me. Today, I don’t think they can say that. I know in my own small way, I’ve enriched the community. Talk to my students, talk to my former students, talk to my military mates, talk to my co-workers.”

Discuss: What does it take to gain acceptance as a refugee? Tell us what you think, in the Global Nation Exchange.

Collins works closely with Soft Landing Missoula, a grassroots group that led the push to reopen the IRC office and secured the support of local officials, like the mayor and the county supervisors. He’s also on the board of several organizations in Montana, included Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services.

“Education is the key. People will hear things and not research. I went through that process. I went through the bigotry, I went through the racism, and in the end I stayed here. That means something. There are good people here. I think the Syrian refugees will be accepted, but with every initial crisis, there will be a lot of negativity going on. We just have to stand firm and tell the truth,” Collins says.

And part of that truth is found in his experience.

“The only thing they’re looking for is a second chance at life. Believe me, I was dying of starvation. The US gave me a second chance. I will never abuse it. “

Coming up: What does it take to bring refugees to the neighborhood? The IRC opens up shop in Missoula.

About eight months ago, Collins met a Cuban refugee couple, Adonis Antolin and Maie Lee Jones, who had moved to Helena with their two young daughters. Helena is not a diverse town by any measure — according to the 2010 census, it’s 93 percent white and 0.6 percent African American. Antolin is Afro-Cuban and told Collins he was worried about how he and his family would fit in.

“He told us to be patient because here, it’s different. There aren’t that many Latino people or black people. He told me not to feel scared because people here are very nice,” Antolin says.

Collins also helped the family get access to basic services while they got on their feet and gave them advice on things like where to get the best food. Now, Antolin works as a maintenance worker for a nonprofit while Lee Jones works in data entry. They are glad they stayed.

“We were thinking of going to Miami, but he was one of the people who told us to stay. He said Helena was a good place to raise a family. Thanks to him, I’m here, really,” Antolin says.

Antolin's change of heart didn’t surprise Collins.

“I’ve been here 22 years. I’ve never once thought about leaving. It says a lot,” Collins says. “I came here speaking English, so what about the refugees that are coming from Syria that are Muslim? I think they will experience some racism, I think they will experience some bigotry, but all in all, at the end of the day, I think there will be acceptance.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!