What everyday life is like for transgender people living in North Carolina

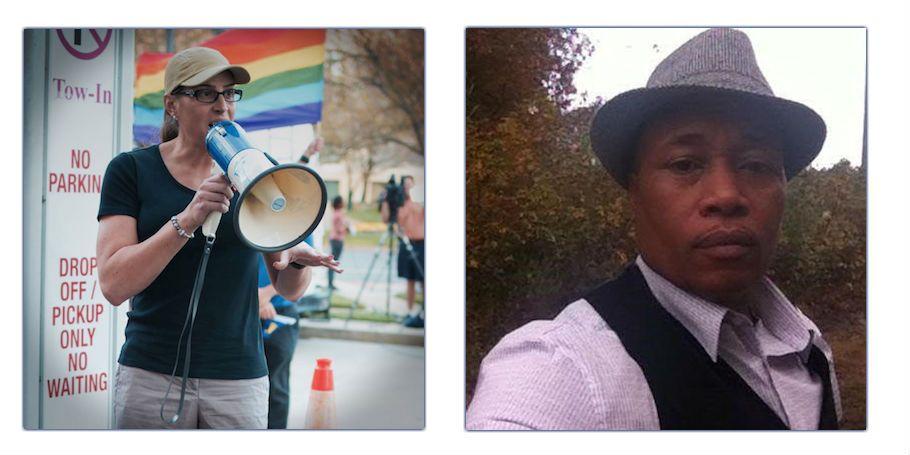

Erica Lachowitz, left, a trans woman, and Austin J. Fonville, a trans man, both live in North Carolina.

North Carolina's controversial HB2 ordinance — commonly referred to as the "bathroom bill" — prohibits transgender people from using public restrooms that correspond with their gender identities. The law has tangible consequences for the bodies and souls of transgender people in the state, says Erica Lachowitz, a transgender woman in Charlotte.

Lachowitz was “looking a little androgynous” when she was out with some friends one night. She needed to use the restroom, and because she didn’t feel like she was “passing” that night, she decided to use the men’s room.

“I felt, you know, not pretty enough to walk into the women’s room without, maybe, having somebody screaming, or having somebody’s boyfriend waiting for me outside to get punched,” she says. “[I thought], ‘I’ll go into the stall, do my business, wash my hands, leave.’ Well, when I went in there, a couple of people came in. I don’t want to swear, but there were some pretty nasty words said to me.”

She continues: “I locked myself in that stall. My palms were sweating. I was anxious. When you sit there so confined and afraid, and then more people start coming in, you don’t know what to do. Your heart is going through your chest and you’re being called these things, and everybody looks at you based off of your appearance. And [you think], ‘This may be it. Can it be that, in a bathroom, I may not walk out of here tonight?’ I don’t want anyone else to go through that.”

Even before he began taking testosterone, Austin J. Fonville, a transgender man living in New Bern, North Carolina, says he never felt comfortable using the women’s restroom.

“I would only like to go if I went with other friends — if I was by myself, I would hold it,” he says. “I had urinary tract infection on top of urinary tract infection because I was just scared to go into the women’s room because I felt like I didn’t belong. No one could see it, but in my mind what I saw myself as did not fit into that room. Every time I would stop and see the door, and you see the [sign] that says male or female, the female definitely didn’t feel right.”

HB2 came as a direct response to a local ordinance introduced by Charlotte's City Council, which protected the right of transgender people to use public restrooms that correspond with their gender identities. When North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory signed HB2 into law, he claimed he was fighting a battle in a culture war.

“This is not an issue I started,” he told FOX News last week. “This is an issue the left started, not the right. It's not just women's bathrooms, it's boys' bathrooms. And, in fact, the Obama Administration is now putting requirements on federal money given to states that they also have to have this gender identification requirement for our schools."

Fonville says he began using the men’s room about six years ago — even before he started “binding,” taping his chest down to make him appear more masculine. He said a man saw him in the restroom “and shrugged his shoulders and finished his business.” Fonville says this experience proves the governor wrong.

“Transgender people have been here, gender-nonconforming people have been here. Governor McCrory created a problem that did not exist, and then he ‘solved it’ by taking the rights away of one of the most marginalized groups of people in our society,” he says.

Fonville believes that most people in North Carolina disagree with McCory and those who support him. Before his name was changed, he says had to go to the hospital. He says he was the first transgender person the emergency room had ever treated, and all of the nurses and doctors were welcoming, and treated him with respect.

“Now there are some [negative] people, but that’s anywhere and everywhere you go,” he says. “I was able to go to a community college — one of the smallest community colleges in all of North Carolina — and all I had to do was tell people who I was, what I was to be called, and what my pronouns were. I used the men’s bathroom, and there was never any problem.”

But all that changed after the bathroom bill was signed into law.

“As soon as HB2 and all this stuff came out, it kind of put me in a different light, and I started to hear things,” Fonville says. “Now, my instructors and all of the staff in the school were fine — they actually, I think, were embarrassed because they put their head down and couldn’t even look at me. But I missed two weeks of school because I was actually too scared to go to school — I was afraid of what would happen when I went into school if I went to use the bathroom."

Fonville says that, thanks to a small group of people “who have an agenda,” the fight against transgender rights has become popular since the Supreme Court upheld gay marriage last year. But Lachowitz, a member of the Charlotte LGBT Chamber of Commerce, says it runs much deeper.

“We were their targets from the very beginning,” she says. “We did a focus group here in Charlotte and we had, before we passed the non-discrimination ordinance, various groups come together and show the pro and the con of what we were looking to do as a city. And I know when we look at the systemic battleground of LGB legitimacy over the past 30 years, we’ve seen some advances and we’ve seen some takebacks. But the religious right, they came out hard.”

When the Charlotte LGBT Chamber of Commerce would hold events, Lachowitz says people from outside of the city would come to protest and shout quotes from Leviticus.

“I am hearing all these Bible verses, but what I’m not hearing is dialogue,” she says. Lachowitz says she’s also offered to speak with Gov. McCrory, Lt. Gov. Dan Forest and other lawmakers in the Tar Heel State about transgender issues.

“If you look at how many years we’ve been trying to get people aware of transgender issues in general — people can understand it, but unless you are a transgender person it’s very, very hard to really grasp [the issues],” she says. “It’s almost impossible.”

In looking toward the future, Lachowitz hopes that the state, and the country, will become a more open and understanding place.

“Five years from now, 10 years from now, 20 years from now, one of the things that I would hope would change is when you see something that is different, you don’t rush to a conclusion, but you pool from as many internal resources as you can and you keep it internal,” she says. “When [people] see things that are different and what they’re not used to seeing, it’s very often too easy to judge.”

Fonville says he hopes the state can move beyond HB2 quickly.

“I think in five years it’ll be sorted out, but I think we’ll look back and be a little ashamed of ourselves,” he says. “And we should be.”

A version of this story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!