30 years after Chernobyl, these Ukrainian babushkas are still living on toxic land

Some of the women who chose to return to their homes near the Chernobyl nuclear plant shortly after the meltdown there in 1986.

Even if you weren't alive back then, you almost certainly know what happened 30 years ago this week — April 26, 1986.

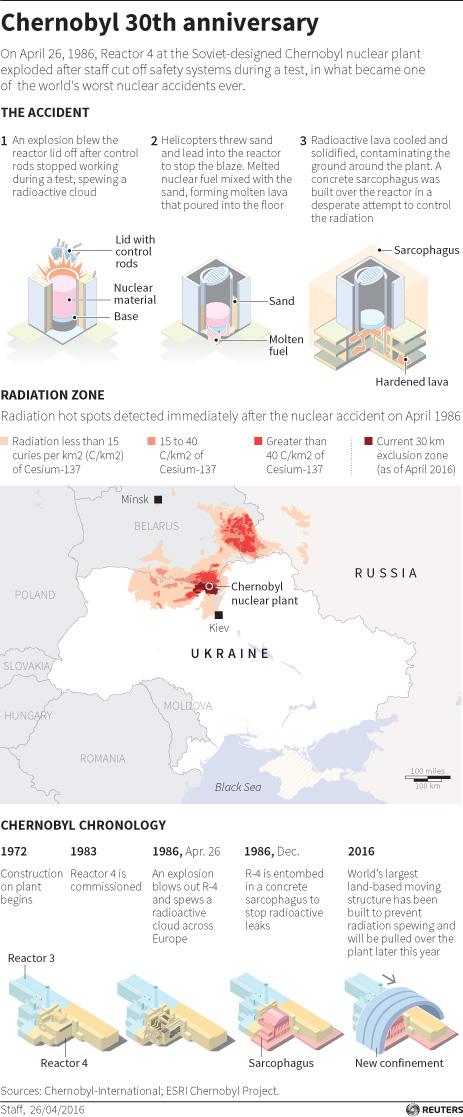

An explosion that day at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in northern Ukraine triggered a partial meltdown.

Without a containment shell around the reactor, a cloud of radioactive material spewed into the air from the plant and spread out over the western Soviet Union and central Europe.

News was slow to emerge from the tightly-controlled country, but before long it became clear that what was unfolding was the worst civilian nuclear accident in history.

Thirty plant and cleanup workers were killed during or soon after the accident. About 350,000 people were evacuated from the area around the plant. The UN estimates that the radiation from the disaster will ultimately kill perhaps 9,000 people. Others say the figure will be much higher.

And today more than a thousand square miles of land around Chernobyl remain officially uninhabitable, a radioactive hot zone for thousands of years.

But about 100 people do live there. They’re the last remnants of more than 1,000 mostly older women who moved back into the exclusion zone in the weeks and months after the disaster.

Their stories are the subject of a new documentary called "The Babushkas of Chernobyl."

The film’s director, Holly Morris, says they were drawn back by “a very deep connection to motherland and home.” It’s where their parents were born and died, she says, where their children were born, where their gardens and animals were. “Home is the entire cosmos of the rural babushka.”

That's “hard to parse against what we all know and fear about nuclear contamination,” Morris says, “but as you get to know their story through the film it starts to make more sense.”

Morris says the women had deep roots in the area, going back centuries. In recent decades, she says, they survived Stalin’s famines, Nazis atrocities and all the hardships of World War II.

“So when a couple decades after that Chernobyl happened, they were unwilling to flee in the face of an enemy that was invisible.”

The “babushkas” were evacuated along with everyone else at first, resettled into high-rise apartment buildings in the nearby Ukrainian capital Kiev and elsewhere, “separated from all that mattered to them” Morris says.

But in the weeks and months after the accident they started going back.

At first they were turned back, Morris says. “But eventually the officials there said, ‘we’ll let the old people return home. They'll die soon, but they will be happy.’”

Many have died in the 30 years since. But Morris says anecdotal evidence suggests that the women who stayed in the exclusion zone have generally outlived their neighbors who stayed away. And she says that “happiness” — or relative happiness, anyway — is a key reason why.

“By coming home, by being on their motherland in the homes that they live their lives in, they avoided suffering the trauma of relocated peoples everywhere,” Morris says.

Relocated people “suffer higher levels of alcoholism, unemployment, and — very importantly in this case — disrupted social networks. And all those things affect your health as well. So by staying in the zone, or returning to the zone, they avoided the detrimental effects of relocation trauma,” Morris says.

“Of course you weigh that against the very real downside of radiation (and) you have a complicated equation.”

It’s complicated for visitors too, Morris says.

When you first go into the exclusion zone she says, you expect “a blighted, post-apocalyptic nuclear wasteland or something like that… You enter through a border, there’s passport control and radiation control. But you get beyond that and it's quite beautiful. You drive through grasslands and fields and trees and wildlife.

“So [there’s a] strange cognitive dissonance going on, because on one hand your Geiger counter may be going off, and your dosimeter, and you’re on red alert in terms of the radioactive contamination. On the other hand, [it’s] a bucolic place.”

Of course it’s hardly a paradise for the aging residents. The very first scene of "The Babushkas of Chernobyl" is of a single babushka talking to herself, telling herself about what she's got in store for the day. It can be a lonely existence as their numbers have dwindled. A village that may have had 20 to 30 people shortly after the accident might now have two or three, Morris Says.

“So it’s a story of self-determination and survival and tragedy and humor, and it all lives together inside the zone.”

And ultimately, Morris says, it’s a story about the power of place.

“Going in I thought OK, making a film about Chernobyl, about radiation, this is going to be bleak. But in fact in the end the film became about home. In the end, home trumped radiation.”

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!