This Kansas high school student must pay back $3,000 after smugglers helped him leave Guatemala

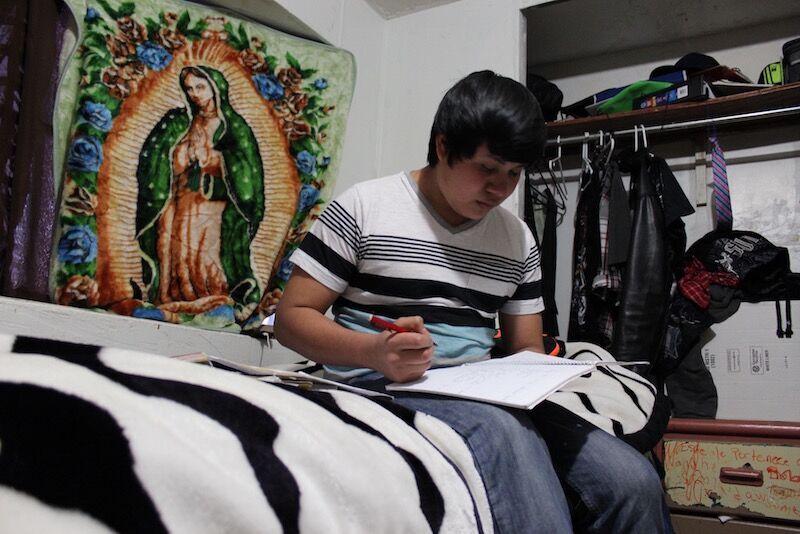

Originally from Joyabaj, Guatemala, Diego studies at the home he shares with his half-brother in Liberal, Kansas. He owes $3,000 in fees, the smuggling costs to bring him to the United States.

In the small, rural city of Liberal, Kansas, a neighborhood of trailer homes sits just off the main drag. In one trailer, with faded yellow paint, I meet a family from Guatemala and Diego, their young relative. He is 17 and came here a little over a year ago.

Diego is also from Guatemala, one of the many young Central Americans who have fled violence and poverty there over the past two years. “I came here because I want to help my mom,” Diego says. “Since I’m her oldest son, I took the opportunity to come here and study and later look for a job.”

In Guatemala, Diego’s mom works odd jobs, like washing clothes. Most days she can barely afford food for the family. She also worried Diego might get wrapped up in the vicious gangs in their town. So it was decided that at 16, Diego would migrate by land to Kansas to live with his half-brother, someone he only met when he got to the US.

Diego asked that we not use his real name. His relatives here are undocumented and Diego is waiting for an immigration judge to decide whether he will be able to stay here or be deported. While he waits, he is a sophomore at Liberal High School.

“I have tough classes, but I like them, especially science," he says.

He also loves learning English, but there’s one problem Diego can’t get off his mind — the debt from the smuggling fee he owes from coming to the US. Diego says he owes nearly $3,000. His half-brother paid the smuggler with the agreement that Diego would work and pay him back once he got to the US. Diego says that debt weighs on him daily.

Sara Carrillo, Liberal High’s social worker, says Diego’s situation isn’t unusual. “When they come here, maybe 10 percent of them have come to join parents,” says Carrillo. “Most of them are with cousins, aunts and uncles, someone from the neighboring village. The host wants them to drop out of school, get a job, start paying rent.”

That’s Diego’s reality. Right now, he’s doing well at school, but he says that soon he’ll have to start juggling his studies and work in order to pay off his debt. Like many of the other young migrants in his position, he’ll probably take night shifts at the local meat packing plant (Diego's half-brother works there too).

One of Diego’s classes is English as a Second Language. His teacher Lori Navarro, says she’s enrolled about 14 new students from Central America in her class over the past year. “You think you have it bad and then you hear everything that they’ve gone through and then what they’re still going through here,” says Navarro.

More: Immigrant student life in the US

In her classroom, there’s a wall lined with photos of her students. Each one has written their own story of immigration, their path to Kansas. Navarro says many of her students have worked at the meat packing plant to pay off smuggling debts or attorney fees. "They work all night and go to school all day,” says Navarro. “Some of them probably don’t even get that much sleep and then they’re back at work.”

Carrillo, the social worker, says that nearly half of the Central Americans migrants enrolled at Liberal High last year dropped out before finishing their first year of school. Another seven transferred, but never requested their records to re-enroll elsewhere. Navarro says they sort of vanished — this happens every semester.

“One of our kids that we lost last semester, a bright student and great student, you could tell he didn’t want to go,” says Navarro. “But the choice he had to make was to get a job so he could start providing as well financially.”

As for Diego, he says he wants to graduate and not drop out. Yet he says he needs to pay his half-brother what he owes if he wants to keep living with him. That means Diego will likely spend the rest of high school studying and working, and sleeping just a few hours a day. Meantime, he says he’ll learn as much at school as he possibly can.

Share your thoughts and ideas on Facebook at our Global Nation Exchange, on Twitter @globalnation, or contact us here.