Any number of Syrian refugees may be too many for Trump

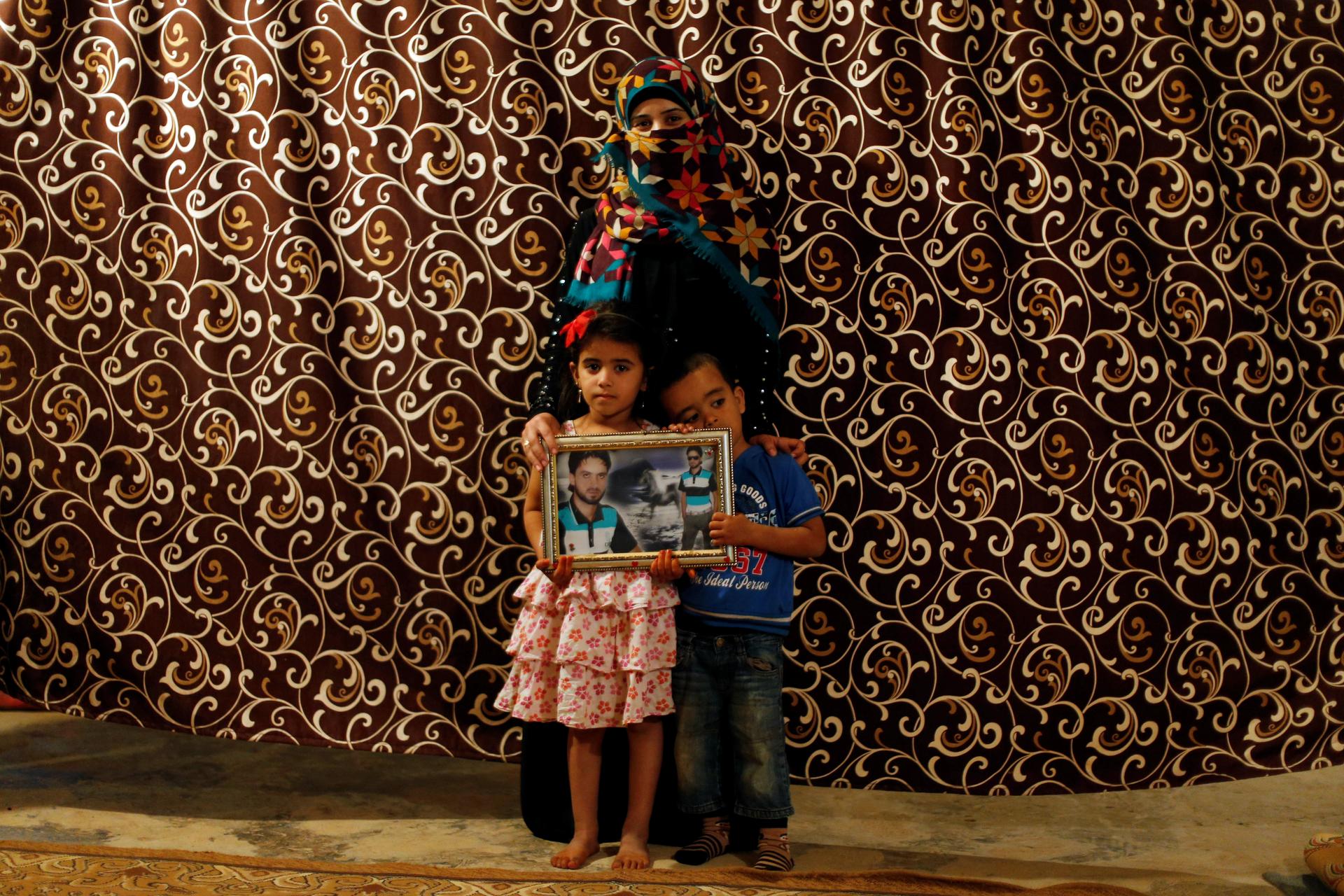

A Syrian family with a photograph of the children's father, a fighter who was killed during fighting against forces loyal to Syria's President Bashar al-Assad.

In early 2015, Gasem al-Hamad and his wife, Wajed al-Khlifa, along with their four young children, arrived in Turlock, a small rural city about two hours from San Francisco. It marked the end of a three-year journey, after fleeing war in Syria, seeking safety in Jordan and waiting to find out where they would next call home.

Today, the kids are in school, and Hamad and his wife are learning English. The family has also found community at a nearby mosque. However, when ISIS militants attacked Paris last November, the family felt a chill. Khlifa, who wears a hijab, said that “things changed.” People stared at her. She hoped “for peace soon in Syria.”

That peace hasn’t come. Syrians continue to flee a devastating war, and that chill the family felt may now freeze out Syrian refugees from the US altogether.

During his campaign, President-elect Donald Trump said Syrian refugees were “definitely, in many cases, ISIS-aligned” and that he would block their entry to the United States. This fit Trump’s plan to tighten immigration policy and his anxiety-provoking rhetoric about terrorists entering the country. Trump’s son, Donald Trump Jr., kept with the tone, comparing Syrian refugees to poisoned Skittles. "If I had a bowl of skittles and I told you just three would kill you. Would you take a handful? That’s our Syrian refugee problem,” read a meme he tweeted, to which he added: "This image says it all."

What can Trump do when it comes to Syrian refugees? A lot. As president, he can set the annual ceiling for how many refugees the country admits, and from where. It is a process normally done in consultation with Congress, but the ceiling does not require congressional approval.

So far, there are strong signs that Trump will flex his power and suspend the Syrian refugee program. His transition team suggests that. Kris Kobach, the secretary of state of Kansas, is a known immigration hard-liner who may receive a cabinet post. In a press photograph taken after a meeting with Trump, Kobach holds his 2018 proposal for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). One of the plan’s bullet points includes reducing the “intake of Syrian refugees to zero.”

Refugees from what Trump calls “terror-prone regions” may also be blocked from entry. Somalis may be in this group, especially after ISIS called an Ohio State University student a “soldier” for hitting pedestrians with his car and then attacking people with a knife on Nov. 28. Trump tweeted that the student, a refugee from Somalia, “should not have been in our country.” It was a quick assumption by the president-elect, since there is no evidence yet whether the student, who was killed by a police officer, was actually linked to ISIS.

Yet Trump has focused most on Syrians, tweeting that they were “pouring into our great country.” In fact, the United States has only accepted a tiny slice of the nearly 5 million Syrians who have fled their homes, and far fewer than Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon or European nations have taken in since the war started in 2011. In fiscal year 2014, the US only accepted 105 Syrians. In 2015, that number was 1,682. Only recently, after facing pressure from abroad and at home, did the Obama administration pick up the pace — resettling 12,587 Syrians in the 2016 fiscal year that ended on Oct. 31. More US staff on the ground in Jordan has sped up the screening process.

But any number of Syrian refugees may be too many for the new administration since, Trump argues, there is “no way” to screen people from the “most dangerous countries on Earth.”

Jessica Vaughan agrees. She is with the Center for Immigration Studies, a Washington DC-based research group that supports tightening US immigration and refugee flows. She says that there is no way to verify a Syrian’s background, and that poses a threat. “The risk of ISIS actually succeeding in getting people through our screening system far outweighs our compassion and hope to help Syrians fleeing danger,” says Vaughan.

But a look more deeply at the data doesn't indicate much risk at all. “The reality is this,” states a 2015 study by the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank. “The United States has resettled 784,000 refugees since September 11, 2001. In those 14 years, exactly three resettled refugees have been arrested for planning terrorist activities — and it is worth noting two were not planning an attack in the United States, and the plans of the third were barely credible.”

The vetting of refugees starts from abroad, with refugees filing their claims with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The UN then refers applicants deemed refugees and US agencies then determine eligibility, a process run by the DHS but involving the State Department and other agencies. The process can take many months, in some cases well over a year.

Syrians face extra vetting, including iris scans, a review of their social media accounts and other security screenings.

Becca Heller, who leads the International Refugee Assistance Project, a New York-based advocacy group that supports refugees, says that the current vetting system is solid. “To institute further vetting [of Syrian refugees], I think would look a little bit like we were just looking for an excuse to not let Muslims into the country,” she says.

Gasem al-Hamad and his family know the process well. “They asked me questions for a year and half,” Hamad said in an interview. “Do you have tattoos, wounds on your body? When did your dad die? And your mom? Were you in the army? When did you serve? Where?” Hamad remembers arriving for one in-person interview with a US official in Jordan at 8 a.m. and not leaving until 9 p.m. “There were long breaks, and then more questions,” he says.

Hamad also worries that the fearful rhetoric against Syrian refugees will prevent other members of his family, still living in extreme danger in Syria, from reuniting with him in the United States.

Heller also hears concerns from refugees who have been referred to the United States, but now wonder what might happen to their cases under Trump. “People are afraid,” Heller says. “You have to think about what message you’re sending to displaced people from Syria if one minute the US says that they will consider them, and the next minute they say they won’t consider them, and the only reason they’re given is that we think everyone from your country has the potential to be a terrorist. And these are people who have already been through really horrific persecution.”

There are doubts, though, about just how tough Trump may be when it comes refugees. “Yes, the president has broad authority here, but I think the new administration will be surprised by the level of information obtained about refugees,” says David A. Martin, an emeritus law professor at the University of Virginia who held high-level posts at the DHS and the State Department during the Clinton administration. He was also a member of Barack Obama’s 2008 transition team.

“I think what happens will depend on whether it’s about delivering on campaign rhetoric or taking the next best steps with these programs,” says Martin. “Right now, we are in the middle of an extreme refugee crises, where the suffering in Syria is acute. I do worry that we will lose out on any progress we’ve made so far.”