70 years after the first bomb was dropped on their homes, some Bikini islanders are still awaiting compensation

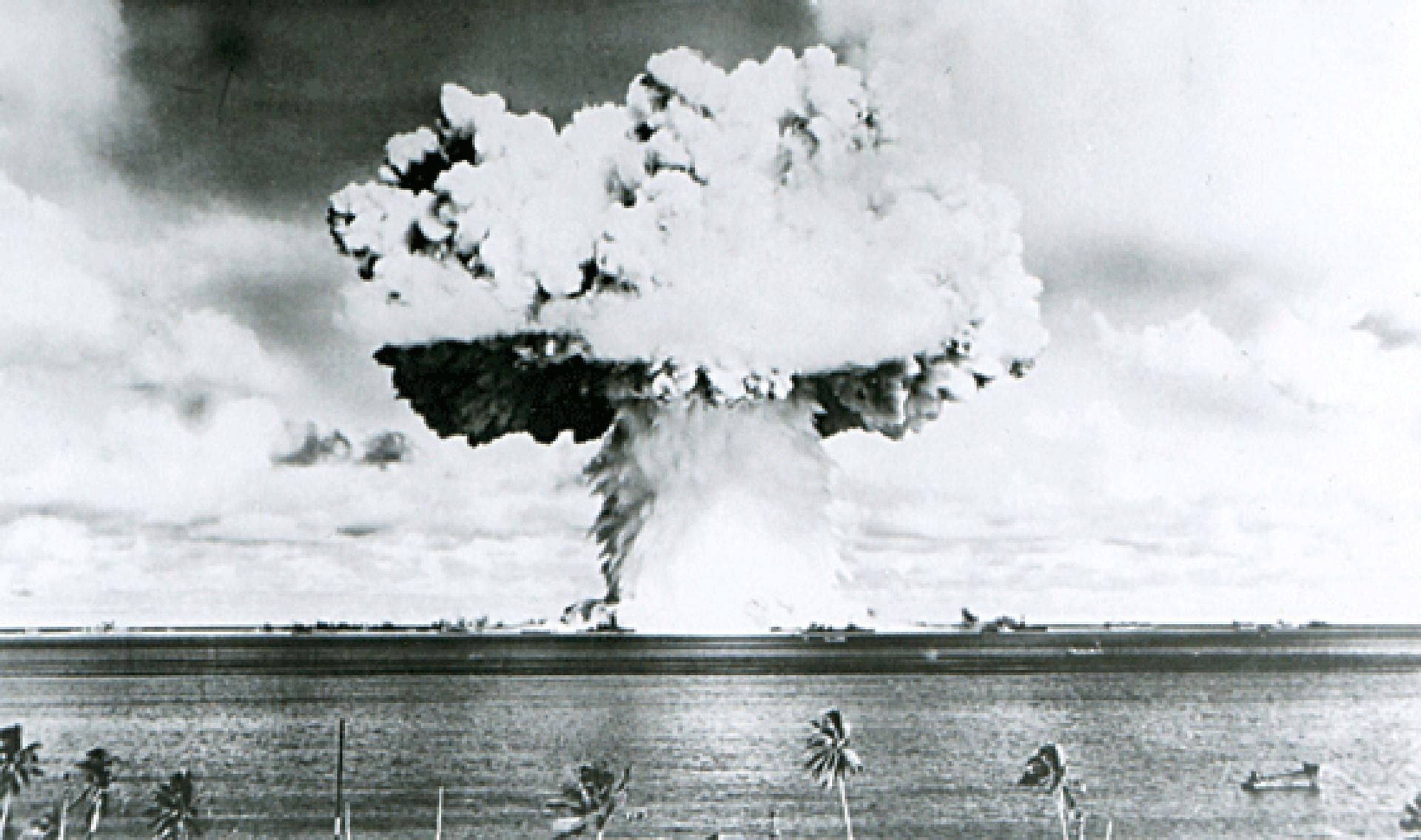

This image shows Baker, the second of the two atomic bomb tests, in which a 63-kiloton warhead was exploded 90 feet under water as part of Operation Crossroads, conducted at Bikini Atoll in July 1946 to measure nuclear weapon effects on warships.

In 1946, French fashion designer Jacques Heim released a woman’s swimsuit he called the “Atome” (French for “atom”) — a name selected to suggest its design would be as shocking to people that summer as the atomic bombings of Japan had been the summer before.

Not to be outdone, competitor Louis Réard raised the stakes, quickly releasing an even more skimpy swimsuit. The Vatican found Réard’s swimsuit more than shocking, declaring it to actually be “sinful.” So what did Réard consider an appropriate name for his creation? He called it the “Bikini” — a name meant to shock people even more than “Atome.” But why was this name so shocking?

In the summer of 1946, “Bikini” was all over the news. It’s the name of a small atoll — a circular group of coral islands — within the remote mid-Pacific island chain called the Marshall Islands. The United States had assumed control of the former Japanese territory after the end of World War II, just a few months earlier.

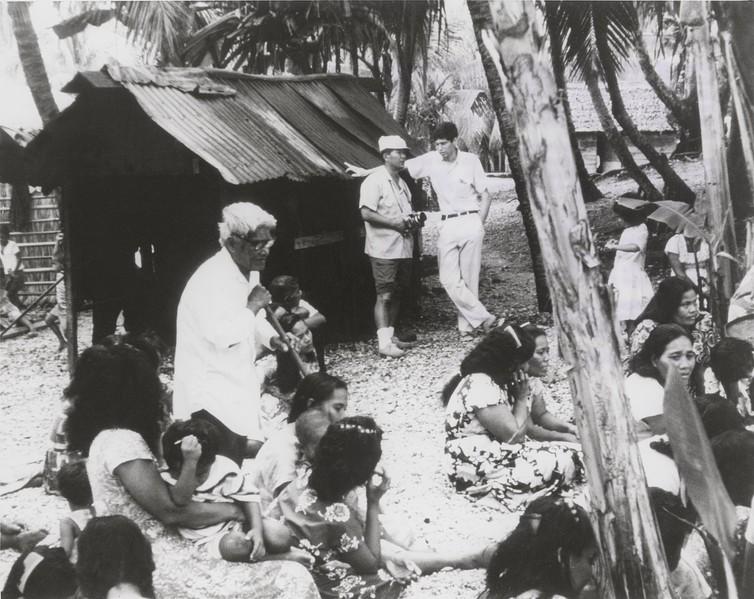

The United States soon came up with some very big plans for the little atoll of Bikini. After forcing the 167 residents to relocate to another atoll, they started to prepare Bikini as an atomic bomb test site. Two test bombings scheduled for that summer were intended to be very visible demonstrations of the United States’ newly acquired nuclear might. Media coverage of the happenings at Bikini was extensive, and public interest ran very high. Who could have foreseen that even now, 70 years later, the Marshall Islanders would still be suffering the aftershocks from the nuclear bomb testing on Bikini Atoll?

The big plan for tiny Bikini

According to the testing schedule, the US plan was to demolish a 95-vessel fleet of obsolete warships on June 30, 1946 with an airdropped atomic bomb. Reporters, politicians, and representatives from the major governments of the world would witness events from distant observation ships. On July 24, a second bomb, this time detonated underwater, would destroy any surviving naval vessels.

These two sequential tests were intended to allow comparison of air-detonated versus underwater-detonated atomic bombs in terms of destructive power to warships. The very future of naval warfare in the advent of the atomic bomb was in the balance. Many assumed the tests would clearly show that naval ships were now obsolete, and that air forces represented the future of global warfare.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3DMV3fQterjEg

But when June 30 arrived, the airdrop bombing didn’t go as planned. The bomber missed his target by more than a third of a mile, so the bomb caused much less ship damage than anticipated.

The subsequent underwater bomb detonation didn’t go so well either. It unexpectedly produced a spray of highly radioactive water that extensively contaminated everything it landed on. Naval inspectors couldn’t even return to the area to assess ship damage because of the threat of deadly radiation doses from the bomb’s “fallout” — the radioactivity produced by the explosion. All future bomb testing was canceled until the military could evaluate what had gone wrong and come up with another testing strategy.

And even more bombings to follow

The United States did not, however, abandon little Bikini. It had even bigger plans with bigger bombs in mind. Ultimately, there would be 23 Bikini test bombings, spread over 12 years, comparing different bomb sizes, before the United States finally moved nuclear bomb testing to other locations, leaving Bikini to recover as best it could.

The most dramatic change in the testing at Bikini occurred in 1954, when the bomb designs switched from fission to fusion mechanisms. Fission bombs — the type dropped on Japan — explode when heavy elements like uranium split apart. Fusion bombs, in contrast, explode when light atoms like deuterium join together. Fusion bombs, often called “hydrogen” or “thermonuclear” bombs, can produce much larger explosions.

The United States military learned about the power of fusion energy the hard way, when they first tested a fusion bomb on Bikini. Based on the expected size of the explosion, a swath of the Pacific Ocean the size of Wisconsin was blockaded to protect ships from entering the fallout zone.

On March 1, 1954, the bomb detonated just as planned — but still there were a couple of problems. The bomb turned out to be 1,100 times larger than the Hiroshima bomb, rather than the expected 450 times. And the prevailing westerly winds turned out to be stronger than meteorologists had predicted. The result? Widespread fallout contamination to islands hundreds of miles downwind from the test site and, consequently, high radiation exposures to the Marshall Islanders who lived on them.

Dealing with the fallout, for decades

Three days after the detonation of the bomb, radioactive dust had settled on the ground of downwind islands to depths up to half an inch. Natives from badly contaminated islands were evacuated to Kwajalein — an upwind, uncontaminated atoll that was home to a large US military base — where their health status was assessed.

Residents of the Rongelap Atoll, Bikini’s downwind neighbor, received particularly high radiation doses. They had burns on their skin and depressed blood counts. Islanders from other atolls did not receive doses high enough to induce such symptoms. However, as I explain in my book “Strange Glow: The Story of Radiation,” even those who didn’t have any radiation sickness at the time received doses high enough to put them at increased cancer risk, particularly for thyroid cancers and leukemia.

What happened to the Marshall Islanders next is a sad story of constant relocation from island to island, trying to avoid the radioactivity that lingered for decades. Over the years following the testing, the Marshall Islanders living on the fallout-contaminated islands ended up breathing, absorbing, drinking and eating considerable amounts of radioactivity.

In the 1960s, cancers started to appear among the islanders. For almost 50 years, the United States government studied their health and provided medical care. But the government study ended in 1998, and the islanders were then expected to find their own medical care and submit their radiation-related health bills to a Nuclear Claims Tribunal, in order to collect compensation.

Marshall Islanders still waiting for justice

By 2009, the Nuclear Claims Tribunal, funded by Congress and overseen by Marshall Islands judges to pay compensation for radiation-related health and property claims, exhausted its allocated funds with US$45.8 million in personal injury claims still owed the victims. At present, about half of the valid claimants have died waiting for their compensation. Congress shows no inclination to replenish the empty fund, so it’s unlikely the remaining survivors will ever see their money.

But if the Marshall Islanders cannot get financial compensation, perhaps they can still win a moral victory. They hope to force the United States and eight other nuclear weapons states into keeping another broken promise, this one made via the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

This international agreement between 191 sovereign nations entered into force in 1970 and was renewed indefinitely in 1995. It aims to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and work toward disarmament.

In 2014, the Marshall Islands claimed that the nine nuclear-armed nations — China, Britain, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia and the United States — have not fulfilled their treaty obligations. The Marshall Islanders are seeking legal action in the United Nations International Court of Justice in The Hague. They’ve asked the court to require these countries to take substantive action toward nuclear disarmament. Despite the fact that India, North Korea, Israel and Pakistan are not among the 191 nations that are signatories of the treaty, the Marshall Islands’ suit still contends that these four nations “have the obligation under customary international law to pursue [disarmament] negotiations in good faith.”

The process is currently stalled due to jurisdictional squabbling. Regardless, experts in international law say the prospects for success through this David versus Goliath approach are slim.

But even if they don’t win in the courtroom, the Marshall Islands might shame these nations in the court of public opinion and draw new attention to the dire human consequences of nuclear weapons. That in itself can be counted as a small victory, for a people who have seldom been on the winning side of anything. Time will tell how this all turns out, but 70 years since the first bomb test, the Marshall Islanders are well accustomed to waiting.

This story was first published by The Conversation.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!