Peru’s presidential race is kinda crazy. These photos give you an idea.

Supporters of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, pictured, and supporters of Keiko Fujimori marched toward each other near Cuzco's main square last month. Both candidates for Peru's presidency are neck to neck in a heated race.

Editor's note: As of Monday, June 6, at 11 a.m., Pedro Pablo Kuczynski had a slight lead over Keiko Fujimori, with votes still being counted.

The back story of Peru's runoff presidential election this Sunday involves mass sterilization, a jailed ex-president, ethnic diversity and guinea pigs.

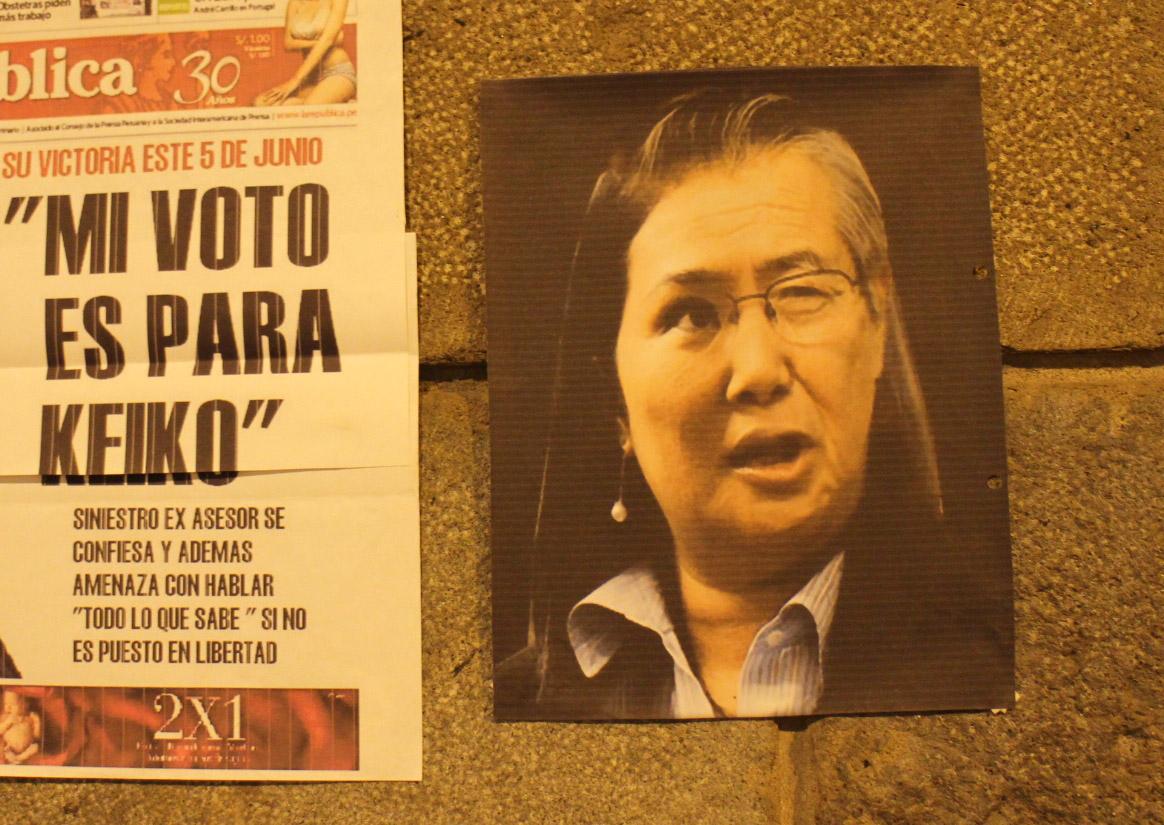

Let me explain: Neck and neck in this race are economist Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, known as PPK, and congresswoman Keiko Fujimori, whose father Alberto governed in the 1990s when the Shining Path guerrilla terrorized the country. Fujimori Sr. fled the country after his second term amid accusations of human rights violations and corruption.

Now he’s in prison back in Peru and until recently, his daughter had been leading in the polls.

I traveled to Cuzco last month, where most people I talked to staunchly oppose a Keiko Fujimori presidency. But despite that, her supporters came out in large numbers when the candidates debated on May 15.

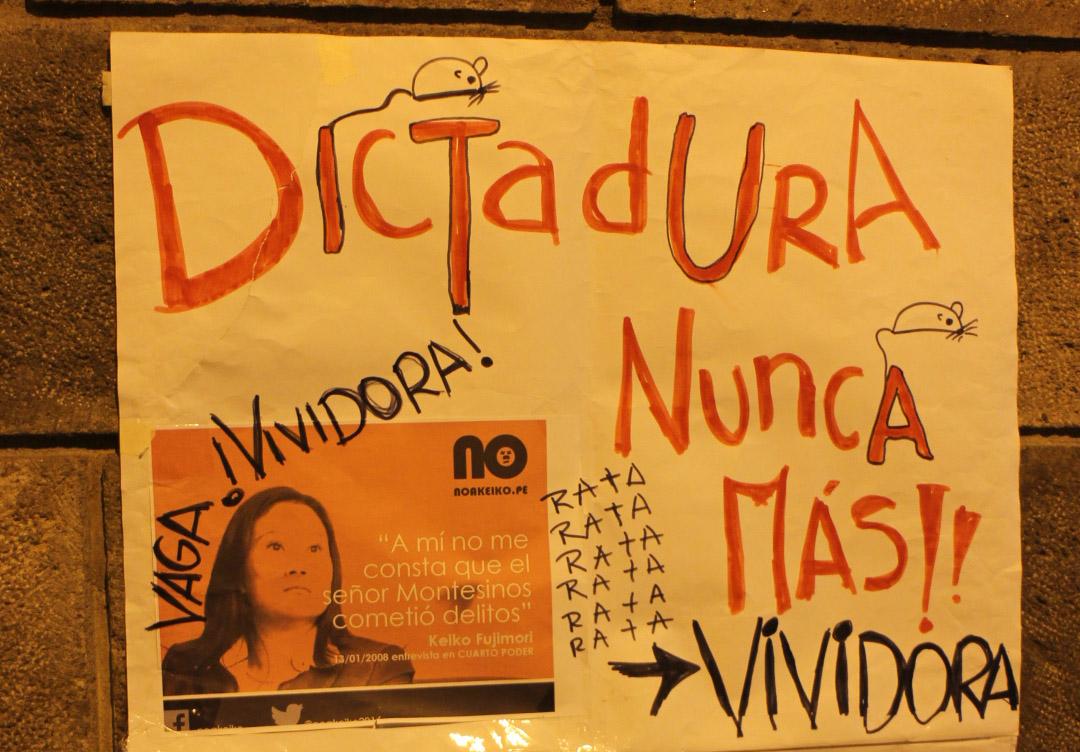

Days after the debate, a group of activists filled a wall near the main square with posters equating Fujimori to her father.

Fujimori Sr.'s presidency ended in scandal partly due to accusations of human rights violations and the sterilization of thousands of indigenous women. The majority of Cuzco's population is of indigenous descent, and local members of anti-Fujimori group "No to Keiko" say they, as descendants of Incas, should be the most vocal against the continuation of Fujimori rule.

This poster reads "Dictatorship never again" and denounces Keiko Fujimori for allegedly living off public money her father stole while in office. Another printout detailed the cost of the Fujimori children's education in US colleges and universities, including travel and housing costs, all allegedly paid for with money meant for government work.

Abigaíl Cárdenas Izquierdo of "No to Keiko" says Cuzco is one of the states in Peru hardest hit by Alberto Fujimori’s crimes — remote towns in the Andes are where guerrilla groups such as the Shining Path and the Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement bred, so the Fujimori administration severely policed the region.

Fabio Venero Figueroa, also from “No to Keiko,” says the candidate was complicit in her father’s crimes, “including the disappearance of entire indigenous communities."

The majority of Peru’s population is of indigenous descent, and presidential candidates often play up their indigenous heritage to get votes — see outgoing President Ollanta Humala and former President Alejandro Toledo.

Meanwhile, this election voters have dubbed the candidates “La China,” referring to Fujimori’s Peruvian-Japanese heritage, and “El Gringo,” playing on Kuczynski’s European heritage and time spent in exile in the United States.

But at the debate rally in Cuzco, Kuczynski’s supporters showed up both in an Inca costume and dressed as the candidate’s mascot: a guinea pig.

That’s one of the biggest symbol’s of Peru’s Inca heritage. Guinea pigs are eaten as a delicacy throughout the country, and they’re beloved representatives of the culture. They appear in every souvenir shop.

At the time these photos were taken, Fujimori was ahead in the race. But days before Sunday's election, the contenders are statistically tied. While Fujimori leans farther right, both are considered pro-business candidates.

An Americas Society/Council of the Americas report shows 34 percent of Peruvians would vote for PPK just to vote against Fujimori.

But Concepción Castillo Guzmán, a health worker in Cuzco, says she’d like to see Fujimori become Peru’s first female president.

“She’s a fighter, like all of us,” Castillo says. “Women make better government.”

Also at the rally was Julia Curo Díaz, an indigenous single mother of six who identified as poor and said she thinks Fujimori would help her get her children an education.

“Sometimes it’s only the rich who can send their kids to school,” Curo says. “I think Keiko will make [education] more equal.”

Venero from “No to Keiko” would say Fujimori has garnered the support of people like Curo by donating food and supplies to poor communities.

“It’s not fair that these politicians take advantage of ignorant people because they give out free rice,” he says.

As of last week, most voters I spoke with in Cuzco and then in Lima were vacillating between the candidates, many considering a null vote.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?