Two Trumps? Filipino Americans can vote in two (remarkably similar) elections this year

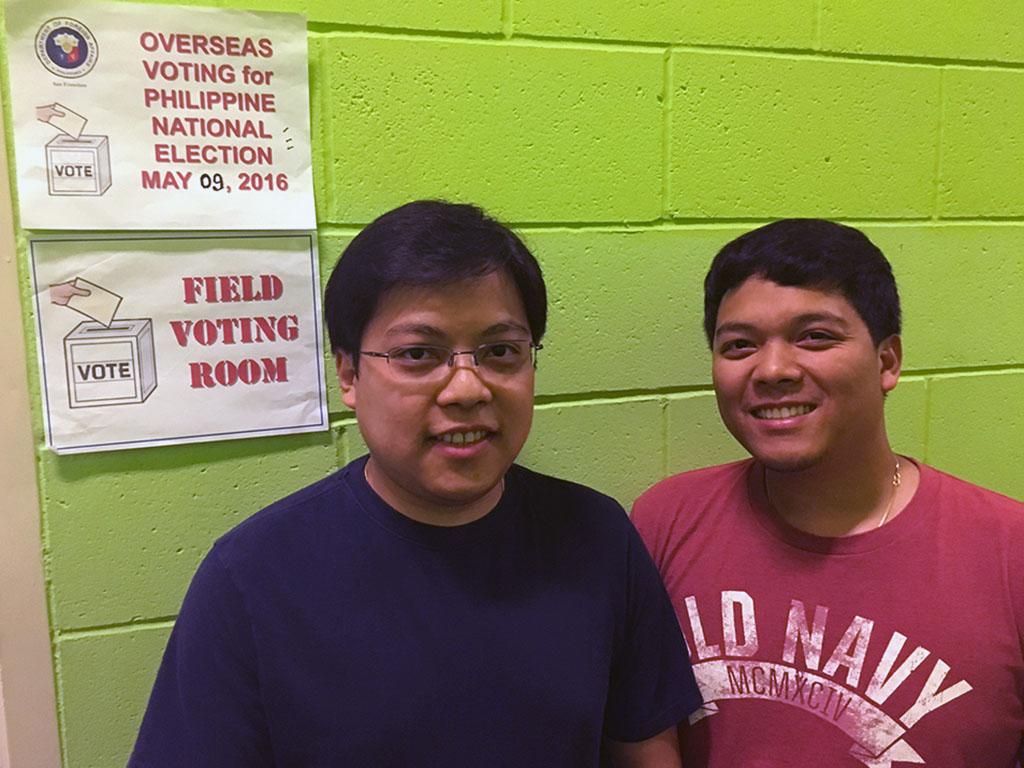

Max Sebolino, 30, and Edgar Louie Sebolino, are dual citizens who voted in the 2016 Philippine election. Both also plan to vote in the US presidential election. They say they are most concerned that corruption in their home country has been rampant and made worse by the current administration.

It’s a typical Sunday afternoon at Seasons MarketPlace in Milpitas, California. Families gathered at the food court enjoy pastries from Goldilocks Bakeshop or a plate of garlic fried chicken, rice and noodles at Chow King.

Shoppers push carts inside the mall’s centerpiece business, Seafood City, a grocery store that carries products from Asia and fruits and vegetables common in the Philippines.

But walk the length of the mall, into a back hallway where the bathrooms and the mall’s administrative offices are located, and there are people lining up not to buy, but to vote.

One of these offices has been transformed into an official polling location for the 2016 Philippines national election. Maximillian Sebolino, 30, is among those who lined up to cast his ballot. He lives in Salinas and drove about two hours with other family members to the Milpitas mall. Sebolino has lived in the US for 19 years — he’s a US citizen. Last year, he applied for dual citizenship and the right to vote in this year’s Philippine presidential election.

“I want my home country to progress,” he says. “I don’t want it to go down the dump.”

It’s unclear how many of these registered voters are dual citizens and able to cast ballots in US races as well. But consulate officials say anecdotal observations show that number is also growing.

“There are some anecdotes that some [Filipino Americans who are US citizens] would come to the consulate to apply for dual citizenship because they want to vote,” says deputy consul general Jaime Ramon Ascalon. “We have a lot of those. And we only observed that this registration cycle.”

2016 is also the first year that the Philippine government is using automated voting in the US, which has allowed for polling locations, such as the one in Milpitas, to be open starting one month before the May 9 election. In the past, overseas voters could only cast their ballots by mail. Consulate officials expect a higher turnout this year because of the automated voting option.

The number of registered voters outside of the Philippines, a country with 100 million people, is about 1.4 million people, 2 percent of the 54.4 million registered voters. But this year’s election has drawn more attention among Filipino American communities, in part, because of the colorful candidates.

Filipinos will vote to replace President Benigno Aquino III, who has served the maximum of six years in office. Among the candidates is brash and tough-talking Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, dubbed the “Donald Trump of the Philippines.” Like Trump, he remains at the top of the polls despite making shocking statements — for Duterte, his critics decry his rhetoric about women, rape and the Catholic Church, which is generally highly regarded in the country. He talks about changing course with China, and negotiating directly with Beijing in international disputes. And like Trump, his willingness to speak off the cuff and say things that make people uncomfortable is a huge part of his appeal for his supporters. Duterte is especially popular in central and southern Philippines where people are suspicious of what they see as an inefficient and corrupt central government based in the north.

Duterte flaunts that he was able to turn his city from being the “murder capital" to one of the safest in the country. But he’s criticized for ruling with a heavy hand and for his alleged support of death-squads believed to have carried out vigilante killings of criminals. In response, he's said that he will continue to be tough on criminals: “I would kill all of you who make the lives of Filipinos miserable,” he said on his weekly television program last year.

Last month, he spoke about the 1989 murder of an Australian missionary: "I was angry because she was raped, that’s one thing. But she was so beautiful, the mayor should have been first. What a waste,” he said at a campaign rally.

With Trump becoming the presumptive Republican nominee in the US this week, dual citizens will have interesting choices to make in both elections.

Duterte’s closest competition is Grace Poe, a senator who is the adopted daughter of a popular movie star. Poe studied at Boston College and lived in Virginia for years before returning to the Philippines. Her critics have questioned her eligibility to run for president and whether she’s “a natural-born Filipino.” She acquired US citizenship in the early 2000s and reacquired her Philippine citizen in 2006.

Another candidate, Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago, is a political veteran who has strong support among youth. Meanwhile, candidates Vice President Jejomar Binay and Manuel “Mar" Roxas II, the grandson of a former president and handpicked successor of the current president, are both being criticized for being part of the country’s elite and political dynasties. Senator Ferdinand “Bong Bong” Marcos III, the son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, is running for vice president and has drawn criticism as well. In the Philippine national elections, voters also elect the vice president.

Sebolino, who was waiting in line in Milipitas, supports Duterte. He says he’s most concerned about corruption and believes the current administration has done nothing to address this problem.

“Duterte can be extreme, but that is what the Philippines needs right now to stop corruption,” he says. “At least with Duterte, he has something to show what he has done to improve Davao when he served as the mayor.”

Sebolino’s older brother, Edgar Louie, agrees. He says he wasn’t planning on voting, but decided to do so because of Duterte.

“Corruption is so embedded in the Philippines that I think he’s what the country needs right now,” he says.

Irene Salazar, 62, also became politically active during this year’s election because of Duterte, but in a different way from the Sebolino brothers. She especially dislikes the candidate’s conduct on the campaign trail.

“The way he conducts his campaign, the cursing, the way he speaks, the way he flip-flops on issues. … I see that as a lack of civility, a lack of character,” says Salazar.

Salazar has lived in the US for 32 years. She plans to retire in the Philippines and says she is concerned about the country’s economy if Duterte becomes president. But she also doesn’t think the country needs another Marcos in a position of power.

“It’s just lots of noise,” says Salazar, who supports Roxas. “I understand that people are clamoring for change. For me, it's not the right kind of change that the Philippines needs at this point.”

If these political debates sounds familiar to you, the parallels have also not been lost on voters who are casting ballots in both the US and Philippine elections. In both countries, the candidates positioning themselves as political outsiders are the front-runners for their parties.

“Both Philippine and the US elections, this year, are interesting, especially when you’re comparing the [candidates’] personalities and their platforms,” says Christian Esteban, a US-based freelance writer for the Inquirer, one of the largest English-language newspapers published in the Philippines.

Voter participation is on the upswing among Filipinos for the US election as well, says Steve Angeles, a Los Angeles-based journalist with the Philippine television network ABS-CBN. This is especially true in California, he says.

“I think for the first time, people are excited,” says Angeles.

Catherine Choy, professor of Asian American studies at UC Berkeley, says this is in part because the political and geopolitical stakes of the elections in both countries are immense. But it's distressing that candidates in both elections have used extremism to appeal to voters, she says.

"[There is] the effective rhetorical use of violence and hatred by some presidential candidates in order to appeal to dispossessed and alienated voters," says Choy.

Angeles says there’s been more effort within both the Democratic and Republican parties in the US to reach out to Asian American voters, including Filipino Americans. Hillary Clinton's rallies in Southern California and Nevada earlier this year attempted to woo this voter bloc.

Meanwhile, supporters of Philippine election candidates have organized and held a smattering of events in California and New York to entice overseas voters.