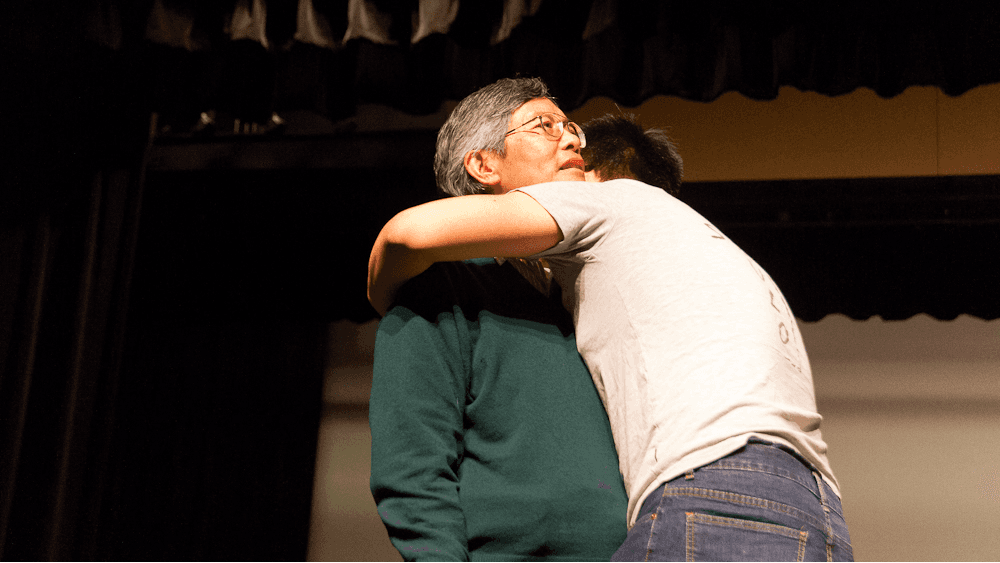

In Millbrae, Calif., mental health professionals stage skits to help parents deal with mental health for their teens. Dr. Alan Louie portrays a father caught off-guard when his son, played by Jason Lee, attempts to give him a hug.

“I need to know if you’re doing something stupid.”

A mother shakes a fistful of bloody tissues while confronting her teenage daughter about fears that the girl is cutting herself. In this case, the “mother” is Stanford University psychiatrist Dr. Rona Hu and this scenario is playing out on a stage at Mills High School in Millbrae, California.

It’s just up Highway 280 from Palo Alto, a wealthy Silicon Valley city that is known for being the home of Stanford University and Facebook. Increasingly, though, it's gaining a reputation for being the home to a troubling increase in teen suicides. Seven years ago, three students from Gunn High School killed themselves; last year, there was another cluster of four suicides at Gunn, Palo Alto High and another private school. Just last week, the death of a recent Gunn graduate was ruled a suicide.

Palo Alto’s teen suicide rate — 10 deaths over seven years — is four or five times higher than the national average. In February, the Santa Clara County Health Department asked the Centers for Disease Control to visit and investigate the crisis. The CDC report is pending. But of note to many mental health professionals here: 40 percent of the victims have been Asian American. In Palo Alto Unified School District, over 40 percent of students identify as Asian.

Since March, Hu and her team of six mental health professionals and one student volunteer have been staging vignettes — a combination of reader’s theater and family therapy — as part of seminars to equip East Asian immigrant parents with better skills to communicate with their teens.

Dr. Helen Hsu, vice president of the national Asian American Psychologists Association, says many Asian, African American, Native American and Latino psychologists have this as a mantra: “Nothing about us, without us."

Many Asian American mental health professionals express frustration about the lack of cultural inclusion in their field. Hsu says research often overlooks minorities. She worries that the CDC findings will not take into account the extra stressors facing Asians.

“The average Caucasian student is not dealing with cultural issues or identity issues,” says Hsu. “There is also the Asian and Asian American stigma towards mental health.”

There have been efforts to include culturally-specific interventions into teen mental health in Palo Alto. Palo Alto Unified School District, which includes Gunn and Palo Alto high schools, worked with Asian Americans for Community Involvement to provide a Mandarin- and English-speaking counselor at the two high schools after the 2009 and 2014 suicide clusters. AACI initially offered the service free of charge. Eventually the district took over funding the position. Soon, a Korean-speaking counselor will be available too, says Dr. Helen Lei, AACI’s main mental health counselor for Palo Alto schools.

“I found the language barrier is a big issue,” says Lei. “There are a lot of first generation families from China. They speak English but they don’t really know how to ask for help.”

For Hu, her parenting seminars are a passion project. She was first tapped by the school district in 2005 because of her training in cultural psychiatry. She and her team volunteer their time to lead these programs, sometimes after working overnight shifts at Stanford Hospital.

From whispers on school playgrounds about Tiger Mothers too focused on academics to debates over school start times, Asian parents sometimes feel they are being unfairly blamed for the stress of local teens. Hu believes that makes them feel isolated, making it even harder to seek help. By publicizing the events on the popular Chinese-language social media platform WeChat, she seeks a majority Asian audience at the seminars so that parents feel comfortable. During the events, the school district provides headphones for translation.

“Not everything is culture,” says Hu, “but you can’t ignore that some things are.”

In one of the skits, Stanford University sophomore Jason Lee convincingly plays a teenager who is more interested in playing video games than studying. Lee, who grew up in the predominantly Asian Southern California city of Hacienda Heights, says the scenarios feel like scenes out of his own youth.

“It’s irresponsible to deal with mental health without culture,” he says.

In each of the seven vignettes during the 90-minute presentation, a counselor comes on stage to talk the characters through alternative ways of handling common — but potentially volatile — situations: They work through mock conversations about bad grades or dating. Asian American mental health experts say it’s critical to introduce families to the idea of mental health support before a crisis situation.

Sometimes the suggestions are a tough sell to the audience. After the skit about cutting — intended to spark discussions about depression and suicide — one father wondered if the bloody tissues represented intravenous drug use. He asks whether these parenting techniques might condone undesirable behaviors.

“I’m somewhat having a conflict about getting rid of the moral aspect to have compassion,” he says.

But many other parents found the presentations helpful. The cultural references — accented English, thousand-year-old eggs and discomfort with physical affection — were an added bonus.

“I could relate to the skit with the suicidal thoughts,” says Millbrae parent Letty Chan. “Because the stress is there.”

Hu spends an hour fielding questions from the audience. When the session is over, she says, “I think we’re getting some momentum.”

She already has her sights set on her next project: partnering with her colleague Joshi to develop a similar parenting program aimed at South Asian immigrants.

May is Mental Health Month. It’s a good time to get familiar with the resources that can help you get through stressful times. You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 (TALK). They offer services in more than 150 languages. The Asian LifeNet Hotline, 1-877-990-8585, works in Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean and Fujianese. If you are in the Palo Alto area, you can reach the Santa Clara County suicide hotline, in English and Spanish, at 1-855-278-4204.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?