Are we close to curing cancer?

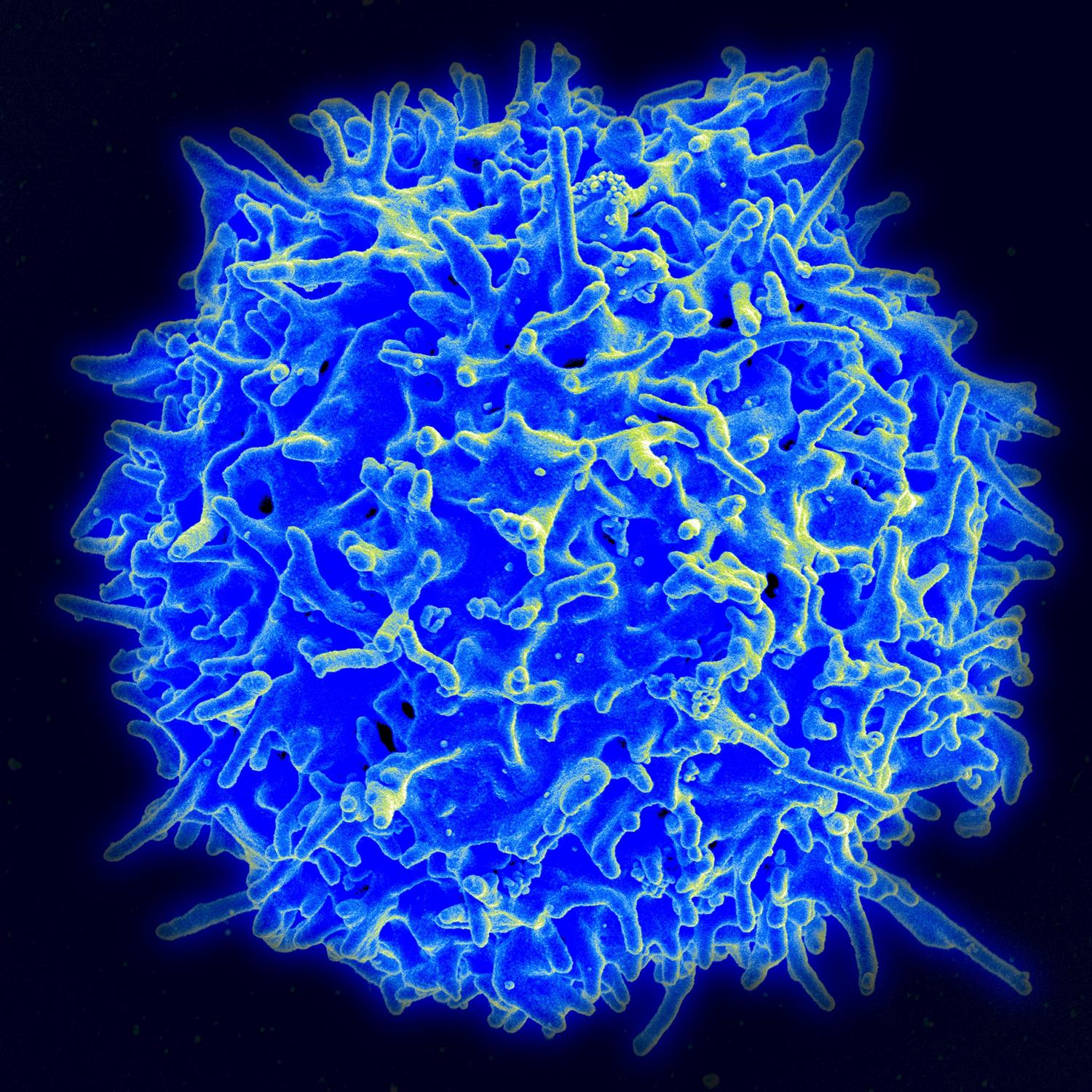

Scanning electron micrograph of a human T lymphocyte (also called a T cell) from the immune system of a healthy donor.

Just months ago, former President Jimmy Carter announced he had melanoma that had spread to his brain. Recently, however, he made the shocking announcement that he was cancer-free. He owes his condition to a new cancer immunotherapy drug known as Keytruda that is giving researchers, cancer patients and doctors new hope in the war on cancer.

Dr. Antoni Ribas who work on immunotherapy treatments for cancer at UCLA says the idea behind the drug is to use the patient's own immune system to attack the cancer.

This isn't a new idea. There is, however, a new development that seems to be actually working. Dr. Padmanee Sharma, the scientific director of the Immunotherapy Platform at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, says the new treatment is sort of like flipping a few “off switches” inside our immune system.

“The immune system is very very powerful,” Sharma says. “But my immune system, your immune system, everyone's immune system has these off switches. … The off switches are important because the off switches make sure that the immune system does not take off and create auto immune diseases. … But if you block these off switches, you allow the immune system to go for longer periods of time, which is what is necessary to allow for tumor rejection in cancer patients. And so understanding the basic immunology, and understanding about these off switches … allows us then to have a powerful immune response against cancer in some patients.”

The immunotherapy treatment has worked for Carter, but studies show that only about 30 percent of cancer patients have had similarly successful outcomes. Sharma says the reason for this gets back to the complexity of the off switches.

“There are multiple different types off switches,” Sharmas says. “The drug that President Carter received blocked one of those off switches, but there are many, many other off switches and so we need to understand which tumor types they're playing a role in and which patients they're playing a role in so that we can block the appropriate off switches. Maybe we need to block multiple off switches so that we allow the immune response to take off and do its job in more patients.”

The FDA has approved immunotherapy treatments for only three types of cancer, but researchers hope that, when further developed, immunotherapy treatment can be used to treat many kinds of cancer.

“The next step is to understand how this happens and why does it work in some patients and does not work in many others,” Ribas says. “That will allow us to think of what's missing in the patients where this is not working and how we can develop a combination therapy that could treat those other patients.”

Still, immunotherapy treatment is a stage in the fight against cancer many people doubted we would ever reach.

“This is an amazing time in cancer therapy, because we now have immunotherapies that are working in multiple tumor types, working in melanoma, kidney cancer and lung cancer,” Sharma says. “We never even thought that was possible that you can take one type of drug and basically have it work across all these different tumor types.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday.