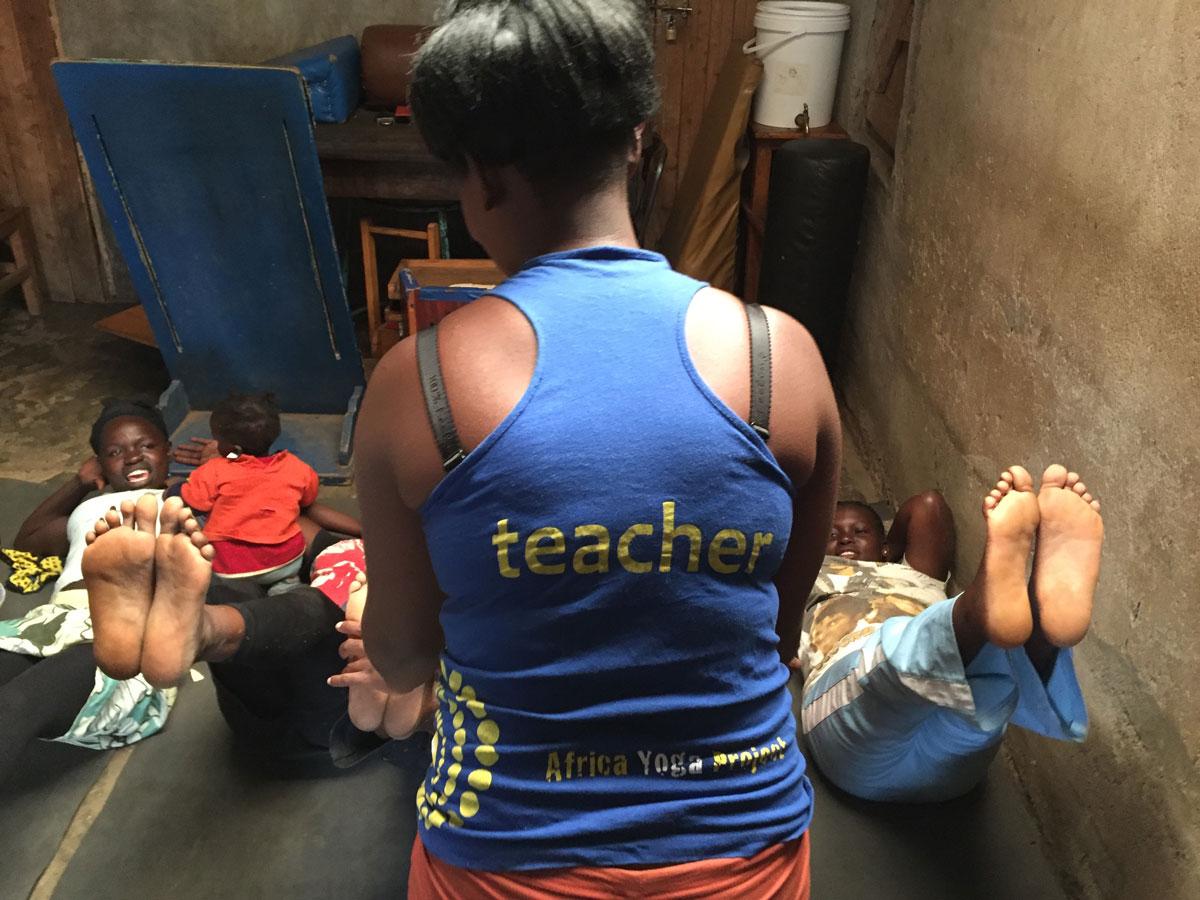

A yoga class for girls and young mothers in the slum of Kariobangi. Mothers bring their kids to class.

I had been in Nairobi for 24 hours when I found myself in a middle-class apartment, the air conditioning turned off, getting run through the paces by Catherine Njeri, a power yoga instructor here.

Within 30 minutes, I looked like I had stepped into a Kenyan downpour.

However, afterward I got to go to my spotless and roomy efficiency apartment, take a shower, and go to sleep in a queen-sized bed. The same is not true for the young women Njeri teaches in the slum of Kariobangi. She was born there, and now is paying forward her success, giving free instruction. Because if ever there was a place where yoga is needed to relieve stress, Kariobangi certainly qualifies.

I practice yoga to relieve stress. But Njeri came to yoga under some of the most stressful conditions on Earth.

“It was a funny story,” she told me. “I think the practice discovered me.”

It was 2007. Kenya had just gone through a disputed presidential election, and the country was burning. Neighbors were killing neighbors. At the time, Njeri worked as an acrobat, and she began touring the country with a group of other acrobats, to camps for people displaced by the violence.

Also in those camps: yoga teachers providing some sorely needed exercise and distraction. Njeri noticed that during the acrobatics performances, different ethnic groups would self-segregate.

But then she watched the yoga classes. “When we were doing yoga, they forgot their differences, and you could see people touching hands on mountain poses. You could see people speaking to each other.”

That was the germ of the Africa Yoga Project, with assistance from American instructors Paige Ellison and Baron Baptiste.

It was also what pushed Njeri from acrobatics to a life of yoga.

These days the Africa Yoga Project includes a teacher training program for Kenyans. And it has spread beyond Kenya’s borders: It offers free scholarships for aspiring yogis from a dozen African countries to come to Kenya and train to become instructors themselves.

Njeri is making a pretty good income instructing expats in Nairobi in yoga. And that helps her take the practice to the community she comes from, the Nairobi slum of Kariobangi, where she helps others learn to teach free yoga classes.

Kariobangi is a warren of shacks, and when it rains, the main street turns into a red slick of mud mixed with the residue of open sewers.

On the day I visited, Njeri was observing a yoga class being taught by one of her mentees, a young woman named Joyce Wanjiku. The instruction was specifically for young women and new mothers, and unlike any yoga class I’ve ever seen. The cement floor was covered in red dust, and the mats hadn’t been cleaned in a while.

But the students packed the room. A lot of them were first timers. One girl told me she was there to improve herself — to “deal with her tummy,” she said. Toddlers crawled across the mats during class. A new mother had to pause several times to nurse her baby. But it was impressive how everyone tried their best to assume the poses Wanjiku was teaching them. They’d slip on the mat and then try again, laughing.

I put to Njeri that perhaps yoga is great stress relief from the pressures of ghetto life. But shouldn’t one deal with the dire poverty first, and then teach yoga? Njeri had clearly thought this through already.

“Acceptance of the situation comes first,” she says. “I was able to accept that I was from the slums. I was able to accept that it was nobody’s fault. That’s what yoga taught me. Now that we have a lot of people doing yoga, it’s because they are starting to realize, ‘It’s nobody’s fault that I’m poor — and yeah, the government has to do something, the world has to do something, but I also don’t have to sit down.’”

I thought back to the class I took with Njeri the previous week. At one point near the end, as we lay there letting our breathing slow down in shavasana — the so-called corpse pose — she told us that yoga is all about acceptance of things you have no control over. That’s been a life lesson for Njeri. But ironically, she’s asserting control of things in her world in Kenya that she wants to change.

One small example: The Africa Yoga Project is trying to reduce unemployment in Kenya.

“Is it working?” I asked her.

She smiled widely. “Yeah! We’ve employed 100 yoga teachers.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?