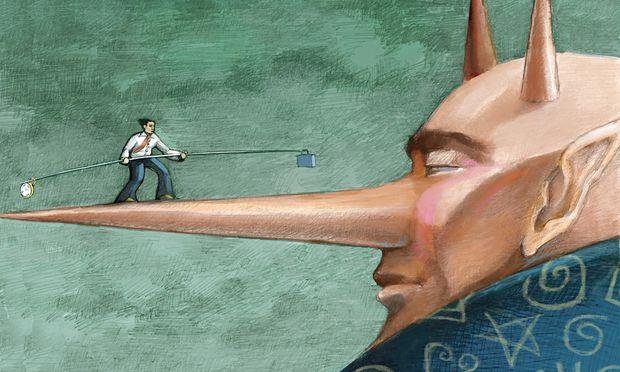

Professor: The truth about really good leaders? They’re often really good liars.

The truth about good leaders is that they are often less honest than they appear.

Leadership development is a $130 billion a year industry. The traditional thought is that good leaders — whether they are CEOs, politicians or principals — are supposed to be honest, authentic and transparent.

But history tells us otherwise. According to Jeffrey Pfeffer, professor of organizational behavior at Stanford University and author of "Leadership BS: Fixing Workplaces and Careers One Truth at a Time,” the average person lies at least twice a day. He says that the truth about good leaders is that they are often really good liars.

“What makes individuals successful is often times the opposite of what people have been told to do,” Pfeffer says. “While we’re told to be modest and honest, and to take care of others and not self-promote, when you actually look at what produces leadership success, at least success as defined as career advancement and achieving a high salary, it’s pretty much the opposite of that.”

Some of the greatest and most successful leaders in the history of business and politics have not always told the truth, Pfeffer says.

“Abraham Lincoln, in order to settle the Civil War, was not completely honest about where the Southern delegation was,” he says. “James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, when asked about whether or not national intelligence agencies were intercepting communications from American citizens, didn’t tell the truth, as we learned from Edward Snowden. And, by the way, Mr. Clapper still has his job.”

When it comes to the business sector, Pfeffer points to Apple founder Steve Jobs, who often employed the “reality distortion field” — a tactic used to convince people of things that they themselves do not believe or are not consistent with reality in order to achieve a goal.

There are plenty of recent examples. Take this statement about the Affordable Care Act that President Barack Obama made back in July 2009:

"Under our proposal, if you like your doctor, you keep your doctor. If you like your current insurance, you keep that insurance. Period. End of story.”

“That’s an example that’s not dissimilar to the Lincoln example — sometimes in order to get a proposal accepted, you can’t necessarily tell everything quite accurately,” says Pfeffer. “Lincoln wanted to settle the Civil War, so he had to make up some lies about the Southern delegation and what the Southerners were willing to accept. When Obama wants to sell healthcare for everyone, he has to probably distort a little bit about some of the specifics of that healthcare plan.”

US leaders at the beginning of the century also lied. Perhaps most famously is this 2003 statement from President George W. Bush:

"Year after year, Saddam Hussein has gone to elaborate lengths, spent enormous sums, taken great risks, to build and keep weapons of mass destruction."

Not so much. But, Pfeffer argues, not all cases of dishonesty are equal.

“In both [the Bush] case and the Obama case, one of the questions is not does a statement, after the fact, turn out to be inaccurate, but whether or not someone knows the statement is incorrect at the moment they’re making it,” says Pfeffer. “There are some people who believe that George Bush actually believed, at the moment he was making that statement, that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, and that it was only in hindsight that they learned they didn’t. A lie is telling something you know not to be true at the moment that you say it.”

One lie has come to galvanize the auto industry in recent days: Just last week, Volkswagen admitted to altering sensors in their cars in order to cheat on emissions tests.

“Lying in the auto industry has a long and glorious, or inglorious depending on your prospective, history and tradition,” Pfeffer says. “One of the interesting questions you ought to ask is why has this gone on and why has this persisted over 40 or 50 years? Let me suggest that one of the answers is because we do not criminalize that behavior. Yes, VW will pay I don’t know how many multiple billions of dollars … but I will guarantee you, with almost no fear of contradiction, that no executive will go to jail.”

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?