Despite the risks, a refugee from Iraq has decided to try to leave Turkey — by jet ski

A street vendor sells balloons which can be used to waterproof mobile phones in the backyard of a mosque filled with Syrian refugees waiting to sail to Greek islands, in the Aegean port city of Izmir, western Turkey, August 10, 2015.

Amer Mohammad talks to his fiancée every morning to tell her what he's doing and that he's OK. On Monday morning, he didn't tell her everything.

Last week, he joined a protest at the main bus station in Istanbul, where refugees asked for the freedom to move within Turkey. Some wanted to go to Edrine, a city on the border with Greece, to try to cross into Europe by land. Others wanted to go to İzmir, to the Aegean Sea, where they would try their luck at a dangerous journey over the waters. Amer, 25, has decided to go by sea.

"I am human. Every human has to be afraid [of this]. I will lie to you if I say that I am not afraid. But there is no other way," Amer says.

This week, police disbanded the refugee camp after a one week stand-off. They offered refugees free bus trips to several cities in Turkey. Amer, who prefers we do not share his family name for security reasons, went to İzmir. There is no future for him in Turkey, he says. He is not allowed to legally work and, like 2 million other refugees there, he cannot gain refugee status. Many people he knows are planning to leave by sea.

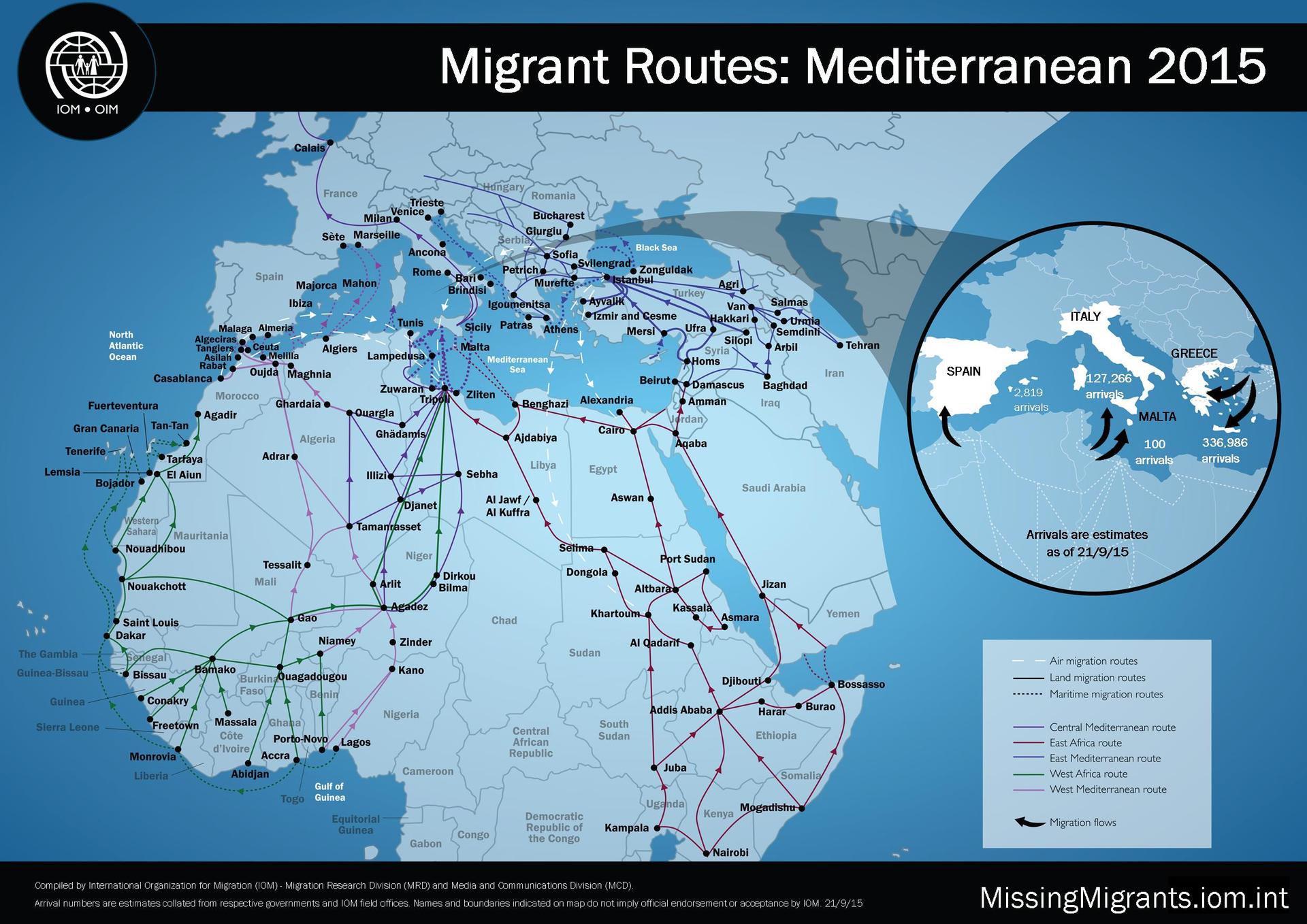

An analysis by the International Organization for Migration found that more than 480,000 migrants arrived in Europe by sea this year, mostly landing in Greece. 50,000 arrived in Greece this month alone, as migrants take the riskier sea route before winter makes it impossible. At least 2,872 people have died in the Mediterranean, including the Syrian toddler who washed ashore in Turkey and whose image galvanized international concern. Another 34 people died while trying to take a rubber boat across the Aegean Sea last week.

European Union leaders are in talks to provide Turkey with more money to block the borders and continue to host the refugees. Over the weekend, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu met with Syrian refugees who are leaders in the camp in Edirne and asked them to wait for the European Union to set up quotas to allow refugees in.

But for Amer, it's just too much uncertainty. It could take months for the European Union to act, and he thinks refugees from Syria would likely be moved first. Amer fled Iraq after a bombing in Ramadi nearly killed him and his family. ISIS has firm control of many cities in Iraq, which has led the US to try and roll the group back in Syria. Amer's fiancée, whom he met in Iraq, was studying in Germany when the violence began. She is still there and his goal is to, finally, be with her.

RELATED: Here's more of Amer's story, how he got to Turkey and why he feels he can't stay there.

He found a dealer, a middleman, to make a transaction with a Turkish smuggler. He is traveling with one of his brothers, a friend from college in Iraq, and a Syrian they met outside the bus station in Istanbul. They are staying in the dealer's house until conditions are right to travel. On Tuesday, after 20 days of camping and traveling, Amer went to a barber for a shave. If he is cleancut, the dealer told him, the police are less likely to notice him.

The dealer initially told him that about 40 people would board a rubber boat, like the kind used by the military, at 3 or 4 a.m., before the sun rises. For 1,200 euros each, they would sail for 90 minutes to get to the Greek island of Samos, south of İzmir in the Aegean Sea. This week, the weather turned bad and the dealer offered a new option: travel by jet ski. They will travel two at a time, plus a driver. The cost is higher — 1,500 euros per person plus a 50 euro fee for the dealer — but the dealer says that this will be safer.

"I really don't trust the smugglers," Amer says, "but I really don't know what to do. These are my options."

He understands that he is putting his life in the smugglers' hands. They will depart from an isolated part of the coast, without police presence but also leaving them alone with the smugglers. He will check his location by GPS on his phone, but they could drop them at any island. It has happened to other refugees. And even if the jet ski trip goes well, once he arrives in Greece, he will still have to find a route to Germany.

He's carrying one lightweight bag with essential items: some clothes, new boots, a first aid kit, a flashlight, medications and his identification papers and documents. He shares a flotation device, a razor and a whistle, with his traveling companions. He has his cellphone and one extra battery — crucial as he navigates his way through borders and communicates with other refugees on Facebook, Viber and WhatsApp. That's also how he is communicating with us when he can. He bought a special balloon to keep his electronics dry during the passage.

He's also been carrying a flash drive in his pocket since he left the Turkish town of Samsun, where the rest of his family has been placed. It holds digital copies of his papers and messages to his friends, family and loved ones in case he doesn't make it to Germany. He hasn't told any of his other family members, his parents especially, about his plans.

"At the end of this I might have a new life, or I will lose all the life that I have," he says.