When America occupied Haiti

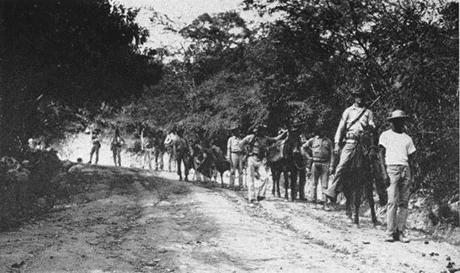

US Marines on patrol in 1915 during the occupation of Haiti. A Haitian guide is leading the party.

One hundred years ago the US began its 19-year occupation of Haiti. It had profound effects on the Caribbean nation. But why did it even happen?

The immediate cause was the violent overthrow and murder of a pro-American dictator, Jean Vilbrune Guillaume Sam. The same day, several hundred US Marines and sailors landed from the USS Washington, which was standing off the capital, Port-au-Prince.

Only one Haitian soldier attempted to oppose the initial landing, and was killed for his trouble, becoming the first casualty of the occupation.

Publicly, the administration of President Woodrow Wilson justified the incursion in terms of re-establishing peace and order. On the face of it, that seemed reasonable, as Haiti had been wracked by political violence and instability for decades. Private armies, known as 'Cacos' could be hired by ambitious individuals and used to seize power.

But the US commander was also instructed to protect US and foreign interests. It was soon apparent that the peacekeeping mission was a cloak for a full-on takeover of the country.

A client government was installed and a new constitution was imposed (interestingly, it was written by a talented young assistant secretary of the Navy named Franklin Delano Roosevelt). The constitution was put to a referendum, and it was reported that only 768 Haitians opposed it, despite a clause ending the prohibition on foreigners owning land in Haiti. That had been a hugely popular principle in Haiti since the revolution kicked out all the French landowners in the 1790s. Many historians agree the referendum and subsequent elections were rigged.

Under a treaty signed with the new government, America took over Haiti’s finances, customs service, police, public works, sanitation, medical services and even the schools. Navy and Marine officers directly supervised these services. A new paramilitary force was established, under American officers, called the gendarmerie.

The Cacos fought back and two bloody campaigns were fought against them. At least 2,000 Haitians were killed, and a Congressional investigation later reported multiple illegal executions. The fighting was intense enough for six Americans to win Congressional Medals of Honor.

But what was the point? Why did the US really go to all this trouble and expense?

There were two main drivers for the occupation.

The first was strategic. The Navy was afraid foreign powers might take over and establish naval bases that could threaten US shores and shipping. In particular, Germany.

It may seem hard to believe, but before the US takeover, a tiny German population had settled in Haiti — about 200 individuals — and they had amassed huge influence over the economy. Among them were believed to be a number of intelligence agents.

Together they controlled 80 percent of Haiti’s international trade. They had also managed to get around the ban on foreigners owning land by being willing to marry into Haiti’s mixed-race elite. They owned and operated utilities, docks, trams and railroads, as well as farms and plantations. They also were allegedly the main financial backers for the Cacos.

The US Navy saw these German settlers as a stalking horse for the Imperial German Navy and wanted to end their influence, just in case there was a war with Germany. World War I had been raging in Europe for a year by the time the US finally took over the country. Similar concerns about German naval influence helped lead to the occupation of the neighboring Dominican Republic in 1916, and Vera Cruz in Mexico in 1914.

Needless to say, German economic and political influence was among the first casualties of the US occupation of Haiti. And German submarines were denied access to Haiti’s ports in the war that did indeed follow.

But when WWI ended, the occupation continued. That’s because of the other main driver behind the take-over: economic and financial interests.

Haiti owed a lot of money to American and French creditors. An American sugar company wanted to be able to own land. Trade and development should meet American needs.

The occupation was an embarrassment for Woodrow Wilson, the champion of self-determination. He caught a lot of flak at the peace conferences in Paris in 1919, after WWI. How could he push for the right of the peoples of the world to form and run their own governments, when the United States was openly preventing that happening in its own backyard?

The US occupation brought a greater degree of political and financial stability to Haiti than it had seen in decades. Huge strides were made in building the country’s infrastructure.

But the costs were high. About 40 percent of Haiti’s national revenue was used each year to pay off US and French creditors. That outflow of money in turn had a stagnating effect on the economy, and took funding away from social services. The US also introduced a form of forced labor — called the corvee — where peasants were forced to labor on roads or build bridges for so many days a year.

Local elites were also marginalized and subject to the racist values of American officials and military personnel, who largely lived segregated lives. Sexual assaults on Haitian women by US military personnel were bitterly resented.

These resentments culminated in a wave of strikes and riots in 1929. A beleaguered US detachment in the city of Cayes opened fire on a mob and killed 12. A Congressional investigation followed and Washington decided to begin a process of withdrawal and “Haitianization.”

But that created new problems. US officials favored lighter-skinned, mixed-race Haitians, who accumulated significant economic and political influence. That caused problems in Haiti for decades to come.

The occupation also triggered a surge in black pride among Haitians of exclusive African heritage. There was a flowering of culture, poetry and writing, stressing the people’s African roots and shrugging off the previous pride in the country’s French heritage.

The US withdrawal accelerated under FDR under his “Good Neighbor” policy, and was complete by August 1934. But direct US influence over Haiti’s finances continued down to 1947.

How did the occupation affect Americans who were stationed there? Well, one Marine officer wrote a famous memoir called "War is a Racket." His name was Smedley Butler. When he retired he was a major general — the highest-rank a Marine officer could attain. He was also the most highly decorated US Marine up to that point in history, having received not one, but two, Congressional Medals of Honor — one of them in Haiti.

But in 1935 he wrote:

"I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism … Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents."

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!