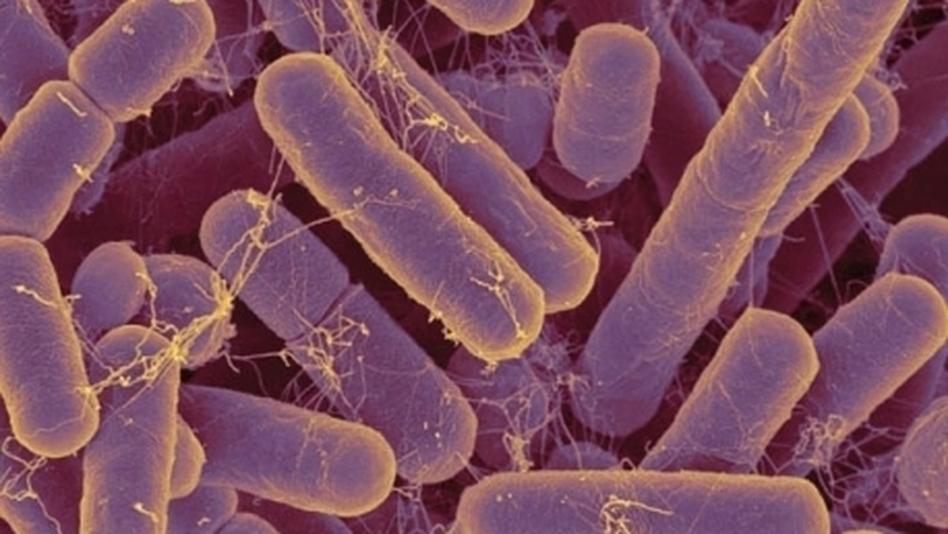

Microbes may hold the key to future high-tech meds and materials

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is harnessing the power of microbial engineering to create the next generation of high-tech medications and materials

When most people think about advanced technology, they imagine robots or hypersonic vehicles or new additions to the Internet of Things. But there is another tool that may have more high-tech potential than anything else: biology.

“Biology can do things that no other man-made technology or chemistry can do,” says Alicia Jackson, deputy director of the Biological Technologies Office at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

“Biology can replicate, it can scale from one to millions to billions in hours; it can adapt, it's programmable through its genetic code. No other technology that we know of can do these things,” Jackson says. The program at DARPA is called Living Foundries.

According to the DARPA website, the goal of the Living Foundries program is “to leverage the unparalleled synthetic and functional capabilities of biology to create a revolutionary, biologically-based manufacturing platform to provide access to new materials, capabilities and manufacturing paradigms for the DoD and the nation.”

“It's a new way of looking at biology,” Jackson says. “If we can program biological systems like we program computers, we might be able to harness those secrets of biology.”

The biotech department at DARPA is not a traditional biomedical science/exploratory program like, for example, the National Science Foundation, Jackson emphasizes.

“NSF is very good is for going across the research community, looking at what's bubbling, and seeding lots of interesting ideas,” she explains. “[At DARPA], we harvest the ideas that are ready for prime time — those we can actually build a new technological capability from. We harvest those and drive them into a product.”

The program is looking, for example, at developing a type of plastic that won’t melt when heated. This type of material could conceivably replace metal parts in aircraft, making them incredibly lightweight, Jackson says.

They are working on creating a new type of conductive wire. “Can you imagine having conductive wires that you could actually stretch and wrap around — so you could truly just roll up your phone or fold it in half?” Jackson asks.

During the Ebola crisis, scientists encountered the difficulties of manufacturing antibodies quickly. DARPA may have a solution to that, too.

“We're interested in something called gene-encoded antibodies,” Jackson says. “Instead of just giving you a protective antibody straight — the protein itself — we want to encode the blueprint for that antibody in DNA or RNA. The magic about DNA or RNA is that all the cells in your body can read it. If we give you that blueprint, the cells in your body can read that code and generate the antibodies itself. We can give you immunity within hours against any infectious disease.”

Despite the promise and the excitement of synthetic biological engineering, biotechnology labs in the US lack two critical things that are found in every other high tech industry, Jackson says.

“Number one is a large amount of computer scientists and data analytics. Biology is a big data problem, but we haven't brought a lot of the tools used in other fields to bear in biology,” she explains.

The second thing is automation. “In biotech labs today, you'll find incredibly sophisticated, highly-trained post-docs still pipetting colorless liquids around by hand,” she says. “That’s crazy. These folks should be thinking about genius ideas that they can implement, not pipetting things around by hand. There should be machines to do this.”

And they need more scientists. There are thousands of researchers working in this field right now, but many more are needed, Jackson says. “We also need people from other fields, not just biology,” she adds. “People who can bring a different perspective to the problem.”

DARPA is very actively recruiting scientists, either to build new programs or to work with them to build new technologies. One of the quirks of DARPA is that scientists can only stay for three to five years. Then they kick you out, Jackson says.

“They want fresh ideas constantly coming in,” she explains. “We don't want a big bureaucracy to grow up within the organization. So it keeps things very nimble — and always keeps things a little crazy.”

This article is based on an interview that aired on PRI's Science Friday with Ira Flatow