Europe blocked it. Why is US allowing Facebook’s new facial recognition feature?

Industry representatives and privacy advocates couldn't come to an agreement during a meeting about how to regulate facial recognition software.

In recent months, debate over the Patriot Act has sparked a renewed interest around questions of digital privacy. But while much of the focus has been on the government’s access to citizens’ digital information, private companies continue to develop increasingly advanced ways to gain information about their clients.

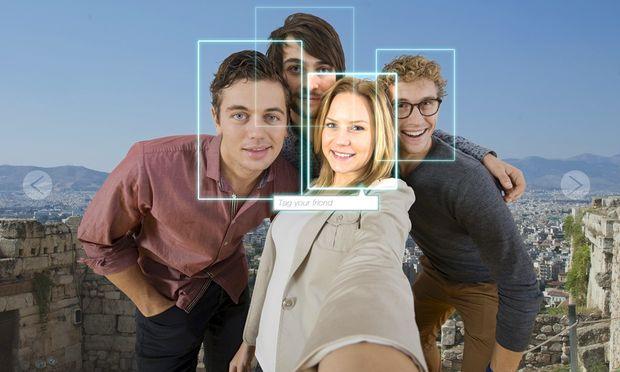

Launched this month, Facebook’s newest service, Moments, raises a particularly difficult question: Who owns your face? Using the date, time and advanced facial recognition technology, Moments organizes and syncs photos of you and people around you in a single place.

Say you’re at a wedding, for example, and everyone is taking pictures of people. Rather than having to upload and then tag your friends manually, Moments will allow you to privately sync all the photos on your camera roll to people in the photos.

The problem, however, is that there is practically no oversight for the use of facial recognition software.

“Facial recognition technology can be used to identify you by name, in secret [and] from far away,” says Alvaro Bedoya, executive director of Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law. “And you can’t do anything about it. You can change your password, you can change your credit card. But you can’t change your fingerprint and you can’t change your face, unless you go through a lot of trouble.”

Bedoya was among a group of privacy advocates that met with trade organizations last week to address the lack of regulation around facial recognition technology. He says that the solution that privacy advocates are pushing for is straightforward.

“We put forward a simple rule that said if you’re a company, you can’t use facial recognition on people without getting their permission first,” he says.

The type of consent would be similar to the model that mobile apps frequently use when tracking a user’s location, with a pop-up asking for consent before implementation. Offline, Bedoya and other privacy advocates are pushing for standard consent consent rules that one would find “in any other business relationship.”

Two states, Illinois and Texas, currently have consent laws in place in order for a company to collect someone’s “faceprint” or fingerprint. But in negotiations for federal regulation, industry-groups did not see a clear solution. Negotiations disintegrated last week, and the privacy advocates walked away from the table.

“Not a single industry association — not one — would agree with that simple rule. And that’s why we walked out,” Bedoya notes.

While Moments is rolling out largely unimpeded in the United States, European regulators have successfully stalled its launch in Europe — the result of their concern of a lack of opt-in mechanism.

Bedoya, though, is hopeful that the larger discussion of privacy in the US will translate to the commercial sphere.

“There’s an increasing acknowledgement that people need privacy in their daily lives. … We need an awareness of that in the commercial and consumer space,” he says.

This story first aired as an interview on PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be a part of the American conversation.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!